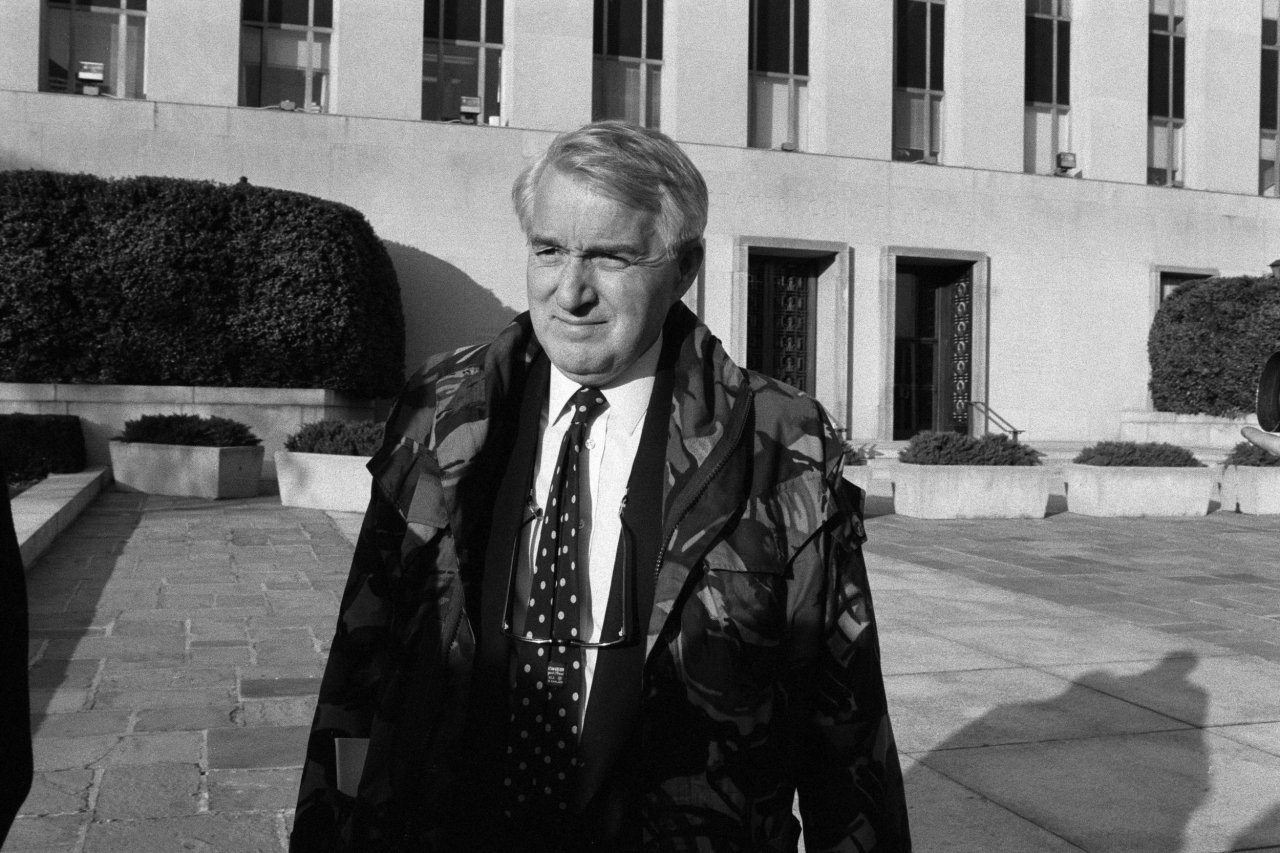

Last spring, I spent a week in Washington, D.C., hoping to interview national security reporters and former CIA officers for my upcoming book, Spooked: How the CIA Manipulates the Press and Hoodwinks Hollywood, and one of the people I contacted was Duane Clarridge, who died from cancer on April 9. Known as much for his love of safari suits and cigars as for his spy-craft, "Dewey" was the CIA's former Latin America director and the founding leader of the agency's counterterrorism center during the 1980s. He also was one of the most high-profile culprits of the Iran-Contra scandal, in which Reagan administration officials illegally sold missiles to Tehran to help raise cash for anti-Communist rebels in Central America. In 1991, Clarridge was indicted for lying to Congress about his role in Iran-Contra, but President George H.W. Bush pardoned him the following year, along with five other intelligence officials.

In 2006, I wrote Kill the Messenger, a book (later made into a film) that probed the CIA's involvement with drug trafficking during Clarridge's tenure, so I figured he might be skeptical about sitting down for an interview. But perhaps the legendary spymaster wasn't big on Google; within minutes of receiving my email, he politely agreed to meet.

On April Fools' Day last year, I arrived at Clarridge's retirement community in northern Virginia. Looking relaxed in a red track suit and tennis shoes, he was waiting for me at a small wooden table at the clubhouse, where we began what would prove to be his last major sit-down interview. Over four hours that culminated with a dinner of Italian soup and a few glasses of sangiovese, he told me his life story: how he was recruited into the CIA by a professor at Columbia University and worked his way through the clandestine service via postings in Nepal, India, Turkey and Italy. According to Clarridge, he never received any official training in spy-craft. Instead, he learned everything from Alexander Foote's Handbook for Spies. "That's all you need to know about real espionage," he said.

In India during the early 1960s, Clarridge claimed he tricked the editor of a small Maoist newspaper in Madras by passing him messages supposedly from Beijing. "I kept pushing him further and further to the left, which was noticed by the Indian authorities," he recalled. In January 1965, the Indian government cracked down, arresting numerous Maoists in Madras state, including Clarridge's dupe. "They cited as the reason this guy's newspaper," he said. "This was a classic operation."

Almost two decades later, Clarridge's proudest accomplishment was turning the Nicaraguan Contras into the largest rebel army in the hemisphere. The idea of molding what he called a ragtag group of "bandits," assembled and trained by Argentina's fascist military regime, came to him almost immediately after he became the CIA's Latin America director. The Contras were officially supposed to prevent the leftist Sandinista revolution from infecting the rest of Central America, but Clarridge fondly recalled how he told CIA Director Bill Casey that their real job was to kill as many Communists as possible. To sweeten the deal, Clarridge explained, "I also told him it would [involve] killing a lot of Cubans."

Because the Contras were far better at attacking unarmed civilians and lining their own pockets than fighting the enemy, Langley often had to intervene directly with sabotage missions. Clarridge said he would stay at the office late at night, listening to radio transmissions from real-time operations involving CIA personnel. Among them: a gunboat attack on Nicaragua's only oil terminal at Corinto, which Clarridge boasted the CIA had "practically burned down." He came up with the most controversial plot of his career—mining the Nicaraguan harbors—one night while drinking gin and smoking a cigar. The mines succeeded in nearly sinking a Russian cargo ship and helped turn the U.S. Congress against the covert war.

"I guess I've been accused occasionally of trying to set off World War III," Clarridge acknowledged, somewhat dismissively.

And what of the Iran-Contra scandal? In Clarridge's mind, the whole thing was nothing more than the media meddling where it didn't belong. "Nobody was ever indicted for going against the Constitution or all this hyperventilating that was going on," he argued. "They were indicted for lying to the Congress or shredding paper." The press, he claimed, was run by Democrats in bed with leftist nuns and hated Reagan's policies and therefore did everything to undermine them.

Clarridge reserved special scorn for San Jose Mercury News reporter Gary Webb, whose explosive series of articles in 1996 claimed the CIA inadvertently helped spread crack cocaine in American inner cities. When the CIA's inspector general sought to investigate that claim, Clarridge refused to answer his former employer's questions, calling them "bullshit." Without realizing my book about Webb was the basis for the recent film, Clarridge marveled at what he saw as Hollywood's depraved bias against the agency. "Oh yeah, the drug thing is a complete canard," he huffed. "It's not true—they even resurrected it in a movie recently!"

Then, after a glass of wine, Clarridge dropped a bombshell, or at least that's what he wanted me to believe. The so-called October Surprise conspiracy—in which the incoming Reagan administration's advance team allegedly plotted to keep American hostages in Iran until after President Jimmy Carter left office—was real, he hinted. He mentioned the 2013 novel October 1980 by George Cave, himself a veteran spook and, according to Clarridge, the agency's top Iran expert, in which a fictional Iranian expatriate businessman enriches himself by aiding a covert American plan to free hostages in Tehran.

"It's a novel, but it's really not a novel," Clarridge explained. The exact date of the hostage release, Clarridge claimed, was set by infamous Iran-Contra middleman Manucher Ghorbanifar, who Clarridge claims had "big bets in Las Vegas—big, big—millions" tied to the outcome of the U.S. presidential election. "What George tells you is the real story," he said, whispering. "The whole novel is really true." (I wasn't able to reach Ghorbanifar for comment. But in a recent interview, Cave told me that he didn't believe Reagan officials plotted to delay the hostage release, but the part about the Iranian businessman was likely true. "Ghorbanifar liked to spend time in Las Vegas," Cave says. "Knowing what he knew, I can't believe he didn't have some bets.")

In recent years, long into Clarridge's retirement from the CIA, it emerged that he was secretly running his own intelligence network along the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Despite his "lifelong distaste" for journalists, his clients included The New York Times, which sought his help in securing the release of reporter David Rohde, who was being held by the pro-Al-Qaeda Haqqani network. Clarridge claimed he also learned of U.S. Army soldier Bowe Bergdahl's capture by the Haqqanis within minutes of the event; the radio traffic, he said, suggested his captors believed Bergdahl was high on hashish. "I know more about the Bergdahl case than anybody in the U.S. government," Clarridge boasted. "I was the first white man to know that he had been picked up."

Before I turned off my tape recorder, the former spy demanded that I run his quotes by him before publishing anything, adding that the last journalist to make that promise hadn't delivered. "He didn't get anything right," Clarridge maintained.

I never contacted him for permission; the cranky ex-spook's interaction with reporters had been so minimal during his career that I didn't wind up using a single line or anecdote for my book. But if I did have to choose a quote from the interview, I think Clarridge would have approved of this one: "All the worst books are written by journalists."

Correction: A previous version of this story mistakenly said that Clarridge claimed Manucher Ghorbanifar had "big bets in Las Vegas" tied to the timing of the deal to release the American hostages from Iran. Clarridge actually claimed Ghorbanifar had big bets tied to the outcome of the U.S presidential election.