The small icy worlds on the edge of our solar system may be better contenders for life than we first thought, scientists have found.

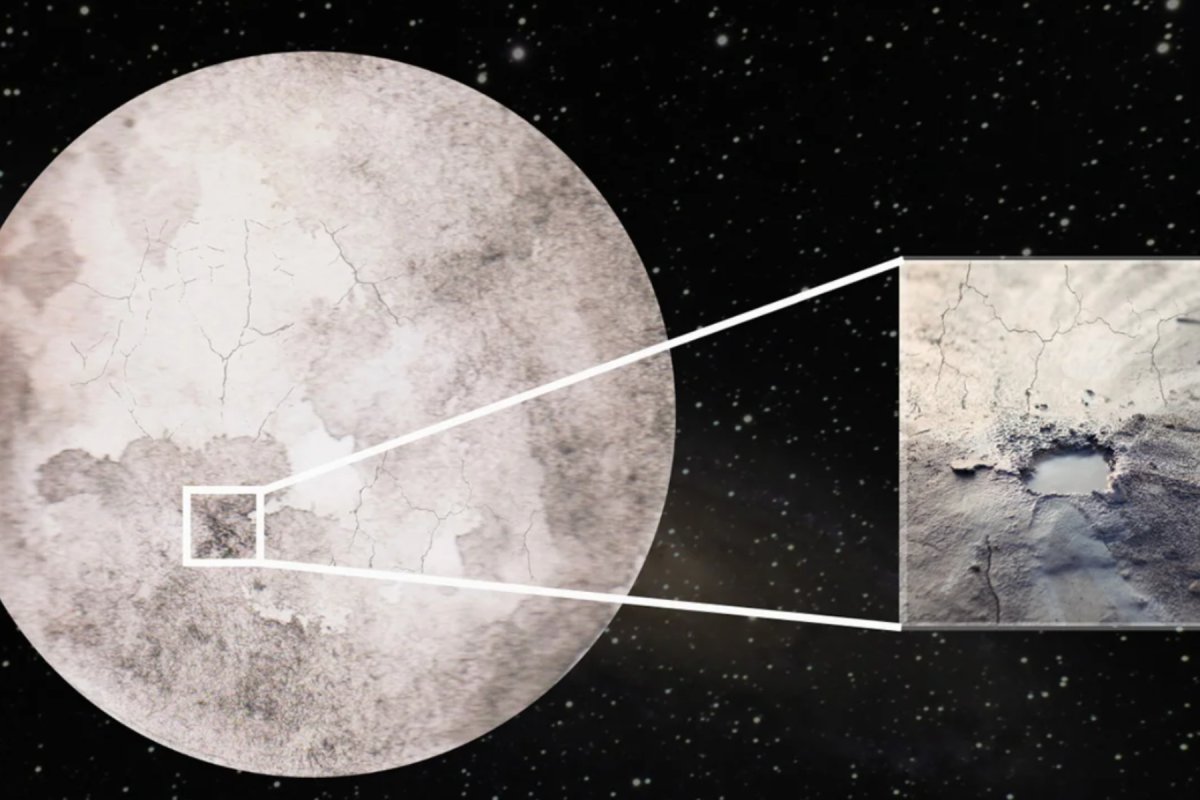

The dwarf planets of Eris and Makemake, situated in the Kuiper Belt beyond the orbit of Neptune, may have geothermal activity beneath their surfaces, according to two new papers in the journal Icarus.

These geological processes were inferred by the discovery of recent methane isotopologues or isotopes—forms of methane differing by the number of neutrons in their nucleus—on the surface of Eris and Makemake. This marked the first time that these methane isotopologues have been discovered on objects beyond Neptune.

This implies that these dwarf planets might be warmer than first thought and, therefore, more capable of hosting life.

Eris and Makemake, alongside Pluto and Haumea, are dwarf planets on the edge of the solar system. Dwarf planets are defined by having enough mass for their self-gravity to pull them into a roughly spherical shape, but they differ from full planets in that they have not cleared their orbital neighborhood of other debris.

Eris is the largest dwarf planet in the solar system, larger than Pluto, and orbits at an average distance of 6,289,000,000 miles away from the sun, about 68 times further out than the Earth. Its diameter is about 1,444 miles across, making it smaller than our own moon, which is 2,160 miles across. Eris orbits the sun once every 557 years, and was named for the ancient Greek goddess of discord and strife.

Makemake is the third-largest known dwarf planet in our solar system, after Pluto and Eris, with a diameter of 888 miles across. It takes about 309 years to orbit the sun. It was discovered in 2005 by the same team that discovered Eris in the same year, and was named after the creator of humanity and god of fertility in the mythology of the Rapa Nui people of Easter Island.

The papers reveal that Eris and Makemake have traces of geologically new methane on their surfaces that could only have gotten there as a result of geothermal activity. This suggests that the dwarf planets may be host to cryovolcanism or even the presence of a hot rocky core.

"This program made the first observations of deuterium and carbon-13 on icy objects beyond the orbit of Neptune," Christopher Glein, co-author of both papers and a planetary scientist and geochemist at the Southwest Research Institute, told Newsweek. "We found that the deuterium/hydrogen ratio in methane matches models in which methane is cooked up from within the interiors of Eris and Makemake.

"This points to geothermal activity. Their observed carbon isotope ratios are normal, which indicates some kind of process that refreshes methane on their surfaces in geologically recent times. It may involve cryovolcanic eruptions from ice volcanoes, or resurfacing due to glacial activity or sublimation cycles."

This discovery was made using data gathered by the James Webb Space Telescope, which allowed the researchers to measure the composition of the surfaces of Eris and Makemake. In particular, they measured the ratio of deuterium or heavy hydrogen to hydrogen (D/H ratio) in the methane present. As deuterium is thought to have formed in the Big Bang, the D/H ratio can reveal the origin and history of chemicals containing hydrogen.

"Even just the presence of methane is evidence of activity since methane that is exposed to space radiation gradually gets broken down to dark, inert material. The fact that we see bright methane ice at all means it has to be at least somewhat mobile on geological timescales in order to stay bright," Will Grundy, paper co-author and astronomer at Lowell Observatory, told Newsweek.

"A good (but not unique) way to keep bright methane ice at the surface is to keep supplying more from the interior. However, it's hard to say whether that chemistry is still happening today, or maybe only happened a long time ago, produced a lot of methane in the interior, and that old methane is still seeping out to the surface today."

The researchers also found evidence in the carbon isotope ratio (13C/12C) of the recent resurfacing of the chemicals on the dwarf planets, further indicating geological activity. This could point to there being liquid water present deep under the surfaces of the planets.

"Geothermal activity can be associated with liquid water, and it tends to generate chemical energy sources that microbial life can exploit. We will need much more information before we get too excited about life in the Kuiper belt, but it's a topic we might want to start thinking about," Glein said.

This, therefore, could make Eris and Makemake contenders for the presence of life.

"Farther in the future, it would be great to send spacecraft back to Pluto and Triton, and also to as-yet unexplored Eris, Makemake, and others," Grundy said. "With modern instrumentation, it would be possible to map out not just the chemical compositions across their surfaces, but also the isotopic ratios. That provides a way of assessing distinct chemical evolution of different geological regions and unwrapping the history of the planets' surfaces."

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about dwarf planets? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Update 2/21/24, 2:16 p.m. ET: This article was updated with comment from Christopher Glein and Will Grundy.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jess Thomson is a Newsweek Science Reporter based in London UK. Her focus is reporting on science, technology and healthcare. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.