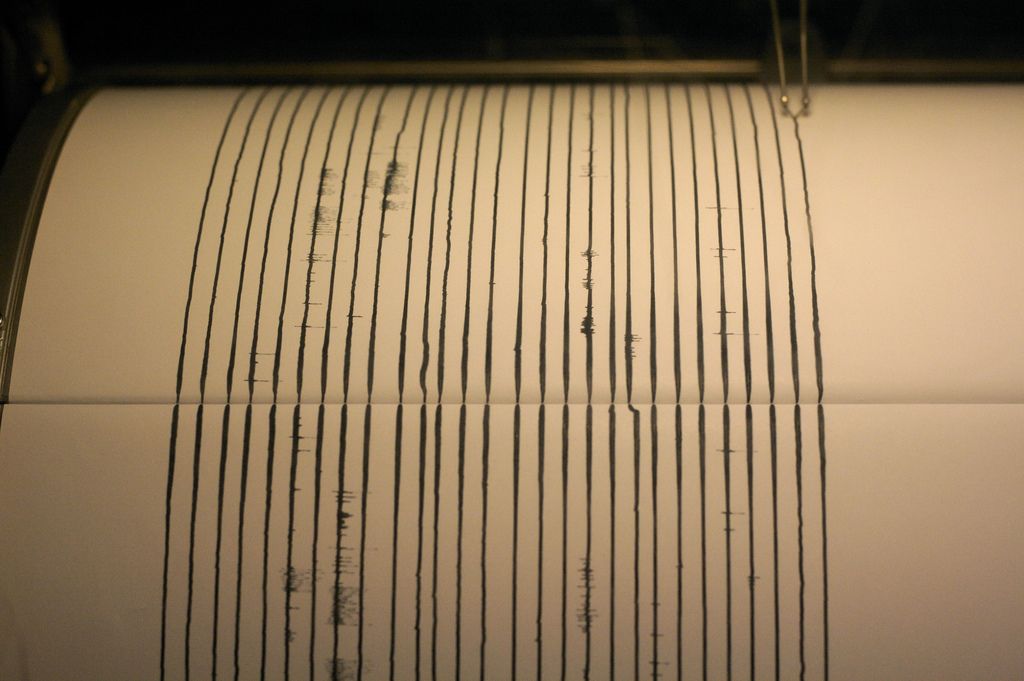

In the past month, parts of Reno, Nevada, have experienced a total of 274 known earthquakes. But if you're surprised you haven't heard about them by now, consider that the vast majority of those have been truly tiny tremors—just five of those quakes have been stronger than a magnitude 2.0, which means they've mostly been too gentle to feel. Some have even been so tiny that seismological networks haven't even alerted scientists there has been a quake. Instead, they've pored through data to identify the small quivers.

According to Ken Smith, an earth scientist at the University of Nevada Reno's Nevada Seismological Laboratory, the swarm kicked off on December 18, then quieted down until January 12. Then seismological activity picked back up and has continued since, although in the past day or so the tremors have slowed down again. "Things are starting to cool off a little bit, so that's good news," Smith told Newsweek.

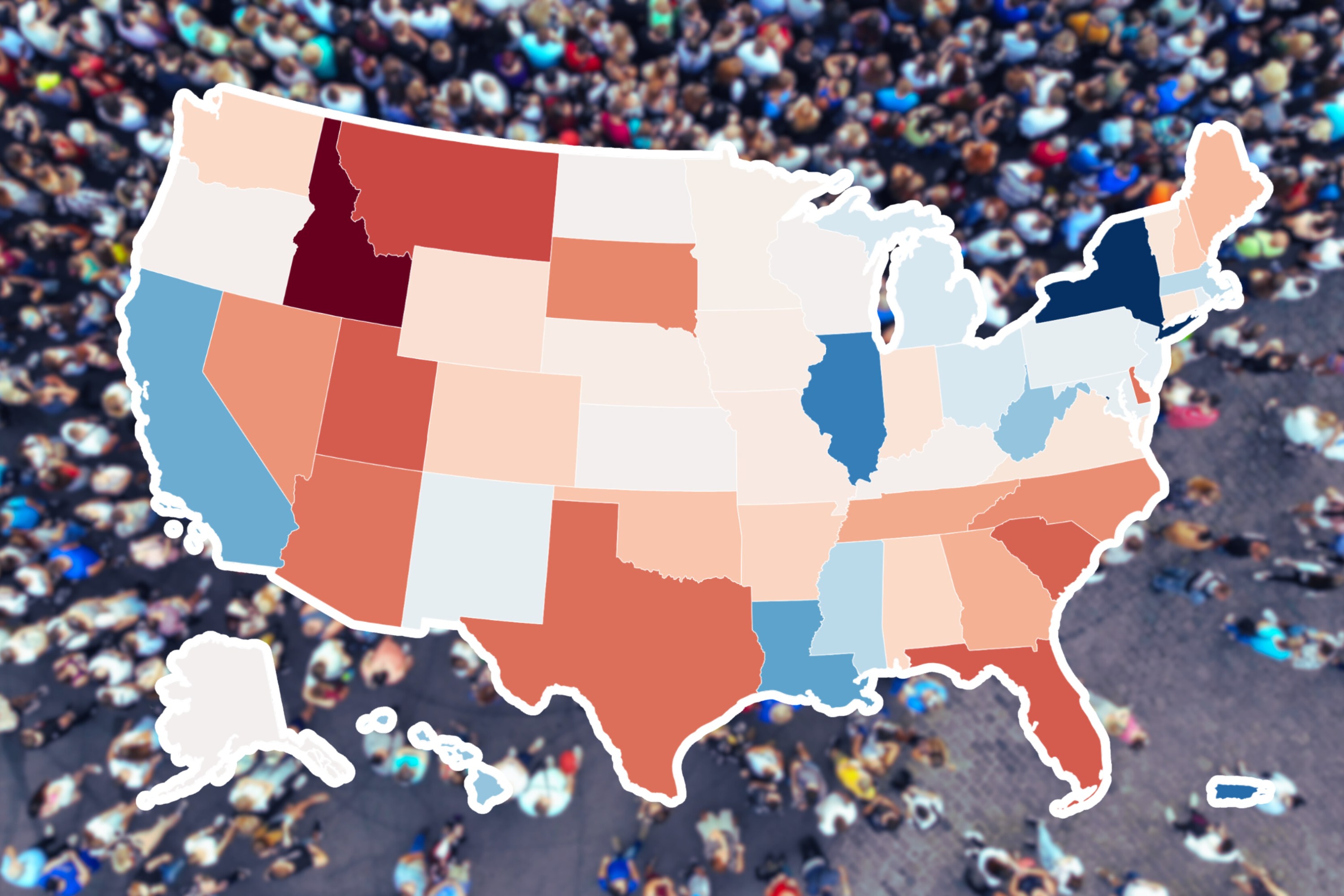

Smith said that the area around Reno is used to seeing swarms of small earthquakes—similar clusters happened in 2013 and 2015. Nevada as a whole is seismically extremely active, with the third highest tally of large quakes in the past 150 years. That's of a piece with the American West at large. "We see swarms like this from time to time, so it's not an unusual occurrence," John Bellini, a geophysicist at the U.S. Geological Survey, told Newsweek. "Swarms sometimes can go on for months."

And along the corridor between Reno and Carson City to the south, scientists are especially well equipped to notice even very small quakes, Smith says, thanks to a particularly dense network of seismographs.

Read more: Huge Earthquakes Can Change the Strength of Gravity Quickly—And Tell Us How Bad Quake Is

Right now, Smith isn't particularly worried about the current swarm. But because scientists know a nearby fault has the potential to cause a magnitude 7 earthquake, and because earthquakes are completely unpredictable, they would rather keep an eye on what's happening underground, just in case they spot any increase in size or strength of quakes.

Technology has also gotten powerful enough that scientists can track the origins of even very small quakes, which can help them identify cracks in the Earth's surface we don't know about yet. "Most of the seismicity here is actually on unmapped faults," Smith said. Finding those will help scientists build a better picture of what's happening underground.

He added that the office coordinates with state and local authorities to decide when to alert the public about seismic activity in the area. That can remind people to make sure water boilers, cabinets and bookcases are secure. Smith says that as of Friday, there haven't been any reports of damage from the current swarm.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Meghan Bartels is a science journalist based in New York City who covers the science happening on the surface of ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.