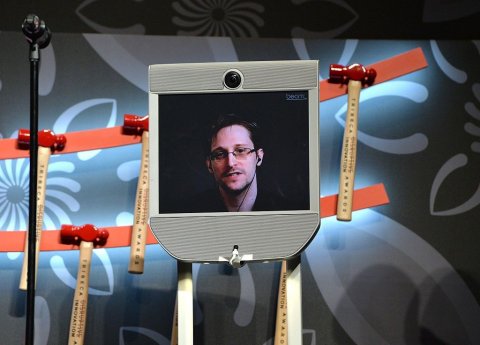

Bill Binney found a seat just inside the door of Washington's Chez Billy Sud, a chic Georgetown pub, as a happy crowd was pouring in after an advance screening of Oliver Stone's new film on Edward Snowden. The entrance was an appropriate perch for Binney, a lanky, 73-year-old former top National Security Agency official who's largely been overlooked in the flood of publicity about Snowden, the infamous electronic-spying leaker who now resides in Moscow.

Years before anyone had ever heard of Snowden, Binney, a gifted cryptologist and mathematician, was pushing back against the NSA's spying overreach. In October 2001, after more than three decades at the agency, he resigned rather than participate in a clandestine, massively overpriced and questionably legal electronic spying system code-named Trailblazer. By most accounts, Binney and his colleagues had successfully designed a system with built-in privacy protections and higher efficiency than that one, called ThinThread. But the agency's boss at the time, General Michael Hayden, ditched ThinThread and poured $1.2 billion into the coffers of contractor Science Applications International Corp. to develop Trailblazer, until the Bush administration terminated it. Ever since, Binney has alternated between grief and rage over his firm belief that ThinThread would have discovered the 9/11 hijackers before they struck.

"It was just revolting and disgusting that we allowed it to happen," Binney says of the September 11, 2001, attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon.

Eventually, the government came after him and his fellow NSA whistleblowers, as well as a House Intelligence Committee staffer, Diane Roark, who had championed their cause. Their story is told in a stunning and deeply disturbing Austrian documentary, A Good American, which is set to open in the U.S. in February. But on this night, Binney, energetic despite losing parts of both legs to diabetes, was surrounded by admirers. And he was thrilled by Stone's powerful biopic of Snowden, who astounded the world with his massive exposure of the NSA's global spying programs.

"I think it's great," Binney says of Snowden, a mostly hagiographic take on the largely self-taught computer expert's journey from patriotic, post-9/11 Green Beret volunteer (he washed out after breaking his legs) to CIA recruit to NSA contractor and eventually apostate and renegade. "It did what I hoped it would do. It shows the human side of surveillance and how it affects people, how it causes them to change their behavior."

For most people, he says, the technical jargon about how the NSA spying programs work, not to mention the complexity of laws that largely fail to control them, is too hard to understand. For years, he tells Newsweek, "I've been talking to different reporters and getting articles written and giving interviews, and people weren't really understanding what I was saying. But with this movie...people can visualize and grasp things. I think it will help people understand what is really going on behind the scenes."

And that is? "That they are invading the privacy of everyone," he says. "They can turn on your cellphone and listen to you. They can turn on your camera and watch you. They can do the same with computers...[even] OnStar," GM's car communications system. "They can use radios in cars to do that. It's a total invasion of what you thought you had as a citizen as rights to privacy."

What the George W. Bush administration freed the NSA and other spy agencies to do after 9/11, he adds, has continued under Barack Obama, with the acquiescence of the Justice Department, despite the president's promise to end the NSA's warrantless collection and storage of bulk phone-call data. Meanwhile, he says, "no one talks about how the FBI, CIA and DEA [can go] into that database and query it for information without any oversight at all." In 2014, the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a civil rights group, gave the president a failing grade on his pledges to curb surveillance abuses.

For the most part, Stone's version of events, based largely on The Snowden Files, a 2014 book by Guardian correspondent Luke Harding, tracks closely with the dissident's own accounts of his growing alienation. His disaffection begins with his CIA posting to Geneva, when the spy agency exploits information collected by the NSA to manipulate and blackmail a foreign banker. Snowden, who had joined the CIA to fight terrorists, hadn't signed up for anything like that. Later, his innocence evaporates when he learns how the NSA's secret partnerships with U.S. telecom companies have allowed it to vacuum up the personal emails, telephone calls and financial transactions of any American with a computer, without a warrant. His estrangement deepens in 2013 when James Clapper, the director of national intelligence, lies under oath during a congressional hearing about the NSA's spying programs. "There are cases," the U.S. intelligence chief said, "where they could inadvertently perhaps collect [intelligence on Americans], but not wittingly." Later, he admitted to deceiving Congress and said his response was "the least untruthful" he could give.

Snowden was watching. He had also seen what had happened to Binney and fellow NSA executives Thomas Drake, Ed Loomis and Kirk Wiebe, whose homes were raided by FBI agents after The New York Times exposed the NSA's secret spying programs in 2005. Drake, prosecuted under the 1917 Espionage Act, was eventually acquitted of all, save for a minor misdemeanor, but his career was ruined. He now works at an Apple store.

All of these events proved to be too much backstory for Stone's focus on Snowden's catharsis. So he invented a sequence in which a comically evil CIA official, apprehensive about Snowden's growing disenchantment, lets his erstwhile acolyte know he's spying on him and his girlfriend. Stone, in a conversation with a journalist at the September 7 after-party in Georgetown, allowed that the scene is a cinematic device to explain Snowden's decision to download thousands of top-secret documents and hand them over to reporters from The Guardian and The Washington Post. The decision will likely re-energize Stone's persistent, mostly right-wing critics, who have hounded the filmmaker for decades over his unconventional portrayals of U.S.-backed Salvadoran death squads, Vietnam atrocities, Wall Street greed and especially the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

But Stone hews far closer to the facts in Snowden than in his other films. The film climaxes with the whistleblower, charged with espionage, fleeing from Hong Kong to Moscow, en route, he hoped, to Ecuador, which has no extradition treaty with the United States. (It's also sheltering WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in its London embassy.) Instead, the State Department, presumably with White House support, revoked his passport, stranding him in Russia.

Now, over three years later, a coalition of human rights groups is launching a campaign to persuade Obama to grant Snowden a pardon. It's not likely to be successful. Putting aside Snowden's depiction as a traitor in many quarters—even Hillary Clinton has said he needs to come home "to face the music"—Obama has shown no inclination to lessen, much less drop, the charges against him. The fugitive's critics insist he should have pursued his complaints internally, despite the persuasive examples of Binney and his comrades that such resistance is futile, even risky. As the PEN American Center, a group of prominent writers that advocates for freedom of expression, noted in a 2015 report, whistleblower protections do not extend to intelligence dissidents when they are "raising valid constitutional or ethical issues about a government action that has been previously authorized by an agency head or Congress as legal."

Binney, meanwhile, contends that the Obama administration has expanded the NSA's spying programs.

"They are collecting vastly more amounts of information every year," he says, with plans to build a massive new data storage facility at Fort Meade, Maryland, besides the one that opened in Utah in 2014. And Binney, who was the NSA's technical leader for intelligence when he retired from the agency, says the expanding dragnets and data dumps don't make America any safer.

"It's all for naught," he says, "because it doesn't help prevent terrorist attacks at all."