Gaber Nassar sits in his ornate office, behind a huge oak desk covered with piles of papers as he explains why the university he leads recently banned women from teaching while wearing the niqab, a veil that covers the face but reveals the eyes. "Everyone has the right to dress how they want, but on one condition: Don't break the rules," says Nassar, the president of Cairo University, one of Egypt's oldest academic institutions.

Some members of Nassar's staff strongly disagree and filed suit to overturn the ban. He jabs his finger at a binder filled with details of all 77 women—university employees who wear the niqab. Nassar says the university's decision to ban teaching in the niqab was informed by research showing a correlation between classes taught by women who wear that veil and low grades among their students. (He declined Newsweek 's repeated requests to share this evidence.) On January 19, a court upheld the ban, but the plaintiffs are expected to appeal.

Nassar insists his ban is not related to politics. But critics, including one of the women in the suit, say the university's policy is part of the Egyptian government's crackdown on dissent, particularly from citizens it suspects might support the Muslim Brotherhood, the outlawed Islamist movement. Since President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi came to power in July 2013 in a popular coup that ousted democratically elected President Mohammed Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, the Egyptian government has effectively banned protests and imprisoned tens of thousands of people, both Islamists and pro-democracy activists.

The el-Sissi government has also involved itself in the personal lives of Egyptians in ways the former regime of the autocratic Hosni Mubarak, who was toppled in 2011, never did. In the run-up to his election in 2014, el-Sissi said, "State institutions have to help us regulate morals that we all think are problematic." In November, he approved the creation of a committee designed to "improve the morals and values of Egyptian society."

Analysts say the regime's drive to control public morals stems from el-Sissi's wish to present the state as the true guardian of Islam and its values, rather than the ousted Muslim Brotherhood or the extremists of the Islamic State militant group (ISIS), whom he sees as the greatest threats to Egypt. "The threat to Egypt's security is real, but the past two years show that the authorities' heavy-handed response has only led to more division," Nadim Houry, deputy Middle East director of Human Rights Watch, said in the organization's January report.

The battle over public morality is a daily one for many Egyptians—and the question of what women should wear, and how they should behave, has increasingly taken center stage. Critics say the Cairo University ban on the niqab—often misinterpreted in Egypt and elsewhere as a sign of the wearer's political leanings—is part of a wider movement by public institutions to control what women wear. In October's elections, officials banned women from voting if they were wearing the niqab, while the prime minister's elections adviser told international observers not to show up at polling stations in "hot shorts." Last year, debates raged on social media over upscale Cairo venues that banned women wearing the hijab.

Wearing too little, however, can get women into as much trouble as covering up too much. When the newly appointed immigration minister, Nabila Makram Abdel Shahid, was sworn in as a Cabinet member this past September, a TV host criticized her for wearing short sleeves. Last April, belly dancer Safinaz (who goes by a single name) received six months in prison after being accused of "insulting the Egyptian flag" because she performed a dance while wearing a costume thought to resemble the national flag (she was acquitted in September). Last June, a Cairo court sentenced dancer Salma al-Foly to a year in prison with hard labor for "harming public morals" after she danced suggestively in a music video. The Egyptian Musicians Syndicat e later banned revealing stage outfits in the name of "recommitting to Egyptian values and tradition."

If there is a model for how the government wants Egyptian women to dress, it is probably Egypt's first lady, Intisar Amer, says Dalia Abdel Hamid of the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights. She favors the "Spanish-style" hijab, or head scarf, worn like a bandanna tied into a bun at the nape of the neck. Local news outlets have described her look as "conservative yet trendy" and "demure," and have contrasted her with the "ultra-conservative" wife of Morsi, who wore a flowing veil.

Critics say this crackdown on women's wardrobes, and on what government officials refer to more generally as public morals, is an attempt to direct attention away from the government's intensifying conflict with jihadi militants and a struggling economy. El-Sissi has spoken of his desire for Islam to undergo what he calls a "reformation," which some analysts interpret as a moderate and state-sanctioned form of Islam. "When Sissi talks about religious reformation, he wants religion to sound sensible and relevant," says H.A. Hellyer, a senior nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington, D.C. "But he also wants it as much as possible to be a tool of the state."

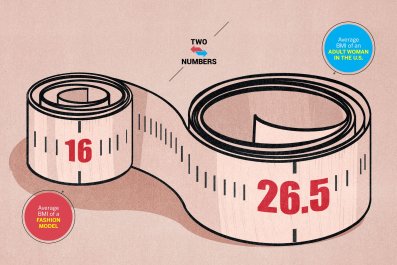

Many women and human rights organizations may criticize the government's sartorial strictures, but polls suggest they are in line with Egyptian public opinion. A University of Michigan survey in December 2013 found that only 14 percent of Egyptians believe women should be able to wear whatever they want. The survey found that 9 percent of Egyptians thought the niqab was the best way for a woman to dress, compared with 85 percent who favored one of several ways to wear the hijab. Only 4 percent said they thought women should wear their hair uncovered.

But even if they are in the minority, women who wear the niqab are insisting it is their right to dress as they wish. The plaintiffs in the suit against Cairo University say the school's decision infringes on their civil liberties. "They said there is a barrier to communication between students and professors. This is simply prejudice," says one plaintiff, a Cairo University professor who has taught at the Faculty of Medicine for 15 years while wearing the niqab. She asked to not be identified; the women involved in the court case have kept their identities secret from the media, fearing reprisals from the university for speaking out. "Their decision is political," she adds.

The professor says the ability of students to see a teacher's face has no bearing on that person's effectiveness as a lecturer. Besides, she says, "In a lecture hall with 1,000 students and a male lecturer, I don't think the people from the third row up can [even] see his face."