There are usually just three ways for a trafficker to leave a Mexican drug cartel: go to prison, get killed, or become a government informant.

Two weeks ago, I had dinner at an expensive restaurant near the Mexican border with a man who got out by the third route. He was, until recently, an important figure in the Sinaloa cartel's drug-running operations, working indirectly for the boss, Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán. Casually dressed, he used a small fork to scrape the marrow from the shank bone on his platter of osso buco. He joked that he wished he had a soft tortilla on which to spread the marrow, the old Mexican way, the way his family did it with a butchered animal.

The informant, who did not want to be named for fear of reprisals, rattled off prices for the drugs he used to transport. They are surprisingly cheap in large volumes: $6,000 per kilo of cocaine in Ciudad Juárez; $1,000 more to deliver the drugs to an El Paso stash house just across the border. Tack on another $1,000 to truck it onward—to New York, Baltimore, Chicago, or Atlanta, where it sells wholesale for around $30,000.

Most criminals who become informants do so because they've been arrested and squeezed, encouraged to betray their criminal employers in exchange for leniency. But this man had an unusual story to tell about his first encounter with U.S. federal agents. It was his boss, a top manager at the Sinaloa cartel, who encouraged him to help the Americans. Meet with the U.S. investigators, he was told. See how we can help them with information.

At the time, Guzmán's huge Sinaloa organization was in the middle of a savage war, trying to crush the Vicente Carrillo Fuentes cartel, known as the VCF. And the Sinaloa cartel wanted to pass along information about its enemies to American agents.

The drug dealer told me how, acting with the full approval of his cartel, he strolled into the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) office for an appointment with federal investigators. He walked through a metal detector and past the portrait of the American president on the wall, then into a room with a one-way mirror. The agents he met were very polite. He was surprised by what they had to say. "One of the ICE agents said they were here to help [the Sinaloa cartel]. And to fuck the Vicente Carrillo cartel. Sorry for the language. That's exactly what they said."

So began another small chapter in one of the most secretive aspects of the drug war: an extensive operation by Chapo Guzmán's forces to manipulate American law enforcement to their own benefit.

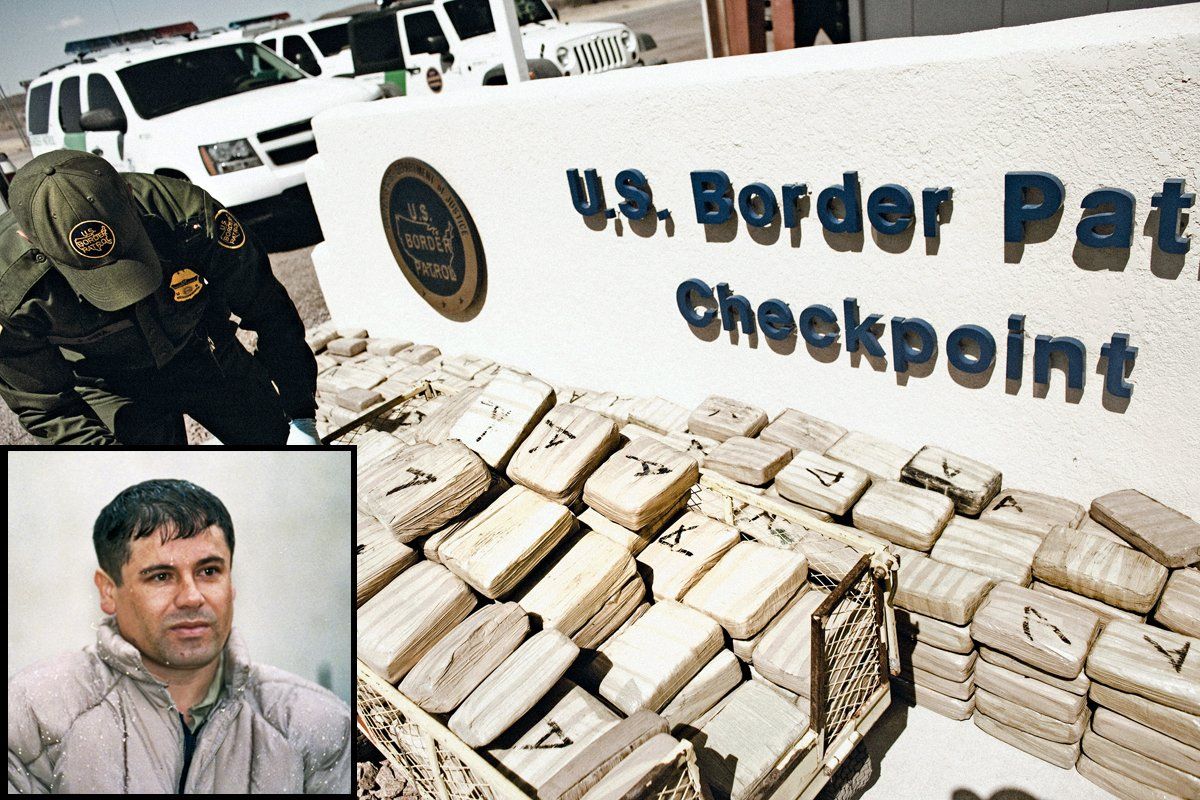

Chapo—who acquired his nickname, which is Spanish for Shorty, because of his 5-foot-6 stature—is a 54-year-old fugitive who has made it to the Forbes billionaires' list for three years running. He's an antihero whose feats of criminality are as astonishing as they are brutal. Ten years after his escape from a Mexican prison, it's widely believed by both Mexican and American law enforcement that he lives in Sinaloa, not far from where he was born. Each year, Guzmán has grown increasingly rich, and the cartel he runs has tightened its grip on the worldwide narcotics trade. A month ago the U.S. Treasury Department labeled him the "world's most powerful drug trafficker."

Guzmán's broad strategy has been to knock off rivals and build his own cartel into the dominant criminal force south of the border. One of his tactics for achieving that has been to place his drug-dealing lieutenants as informants for the DEA and ICE. According to sources and court records, he has been carefully feeding intelligence to the Americans. Now, Newsweek has learned, there is a federal investigation into how ICE agents handled some Sinaloa informants near the border.

The implications are sobering: the Sinoloa cartel "is duping U.S. agencies into fighting its enemies," says Prof. Tony Payan of the University of Texas at El Paso, who studies the cartel wars in Juárez. "Typical counterintelligence stuff. It's smart. It's so smart."

Humberto Loya- Castro, a charming and erudite Mexican lawyer who served as Guzmán's adviser, may have been his most intriguing agent. He became a key informant for the Drug Enforcement Administration during the last decade. A former DEA official describes Loya-Castro as "astute, witty. He was extremely charismatic." His tips led to arrests, seizures, and headlines. Many of those law-enforcement victories, though, were also triumphs for the Sinaloa cartel.

Loya-Castro was indicted by the United States in 1995, along with Guzmán. Back then, the lawyer was known by the alias "Licenciado Perez"—Lawyer Perez. The charges say he "protected the drugs and money of the Guzmán organization in Mexico by paying money to Mexican authorities" and "ensured that if key members of the Guzmán organization were arrested they did not remain in custody."

At the time of the indictment, Chapo Guzmán ran his Sinaloa operation from a Mexican prison. Being behind bars didn't hamper the drug lord, who treated the jail as a private castle where prison guards scurried around like servants.

Five years after the indictment, while Guzmán was still locked up, Loya-Castro first approached American officials, offering to feed them information. To appreciate his potential value, imagine if the leader of North Korea or Iran had a lawyer who offered to become an undercover U.S. operative. As a compadre of the Sinaloa boss, Loya-Castro had information that most investigators could only fantasize about.

After Guzmán escaped from prison in 2001, Loya-Castro continued to feed U.S. agents information. In 2005 he made it formal, signing paperwork that made him an official confidential informant for the DEA. Because he was a fugitive from justice, facing an outstanding warrant, a special DEA committee had to sign off on the whole operation.

He was a productive spy, handing over what seemed like ever more vital information, mostly about the Sinaloa cartel's enemies. The DEA agent assigned to handle him was a relatively new investigator named Manuel Castanon. He had spent five years working for the Border Patrol, then joined the DEA in 1999. He was assigned to a special task force based out of San Diego—a unit that wasn't focused on the Sinaloa cartel. Rather, Castanon and his group were tasked with fighting one of Guzmán's closest rivals, the Tijuana cartel, headed by the notoriously brutal Arellano Félix brothers.?

The Tijuana cartel was small, but it was important because it controlled the vital smuggling routes through Baja California and San Diego. Both the DEA and Chapo Guzmán had an interest in its demise.

One day Loya-Castro called Castanon to set up an urgent meeting. At a briefing with DEA officials, Loya-Castro warned them of a grave threat to their agents coming from one of Chapo's enemies. He explained he had been dining with a former Mexican official when the official's Nextel radio beeped. The caller was a member of the embattled Tijuana cartel who proceeded to outline a series of illegal plans. Loya-Castro could hear the whole conversation as if it were on a speakerphone. The Tijuana cartel was hiring a trained sniper nicknamed "the Monster," Loya-Castro said, to shoot DEA agents and frighten them into leaving Tijuana. (A WikiLeaks cable describes the incident, and while Loya-Castro is not named in it, Newsweek has learned that he was the confidential source called "CS-01-013562.")

The intended effect of such a tip was almost surely to focus the DEA on Guzmán's rivals. It apparently worked: the Tijuana cartel has been mostly dismantled, and Chapo Guzmán has taken over lucrative territory.

All along, Loya-Castro apparently insisted to his handlers that he had Guzmán wrapped around his finger. Guzmán, he said, was gulled into thinking that Loya-Castro was loyal to him. "His point to us," says David Gaddis, a former top DEA official who oversaw operations in Mexico, Central America, and Canada, "was that 'because of my position, Chapo has absolute, unfettered confidence in who I am and what I'm doing.'"

"I do think he was telling Chapo, 'Hey, I'm meeting these guys,'" Gaddis tells Newsweek, "and Chapo allowed him to do it."

Loya-Castro's material was so rich—so helpful in various cases—that in 2008 the U.S. attorney's office in San Diego had the indictment against him thrown out. And the intelligence kept coming. In December 2009, in an operation trumpeted around the world, Mexican Marines encircled and killed Arturo Beltrán Leyva, a leading drug lord who had splintered away from the Sinaloa group. In Chapo territory in Nogales, Sonora, residents fired pistols in the air to celebrate, according to Malcolm Beith's book on Guzmán, The Last Narco.

It's been reported that the Americans provided intelligence that led to Beltrán's death. They even coordinated the signal intercepts that allowed the Mexican Marines to move in, according to a source who was involved. A source close to the cartel leadership says intelligence for the operation also came from Loya-Castro. In essence, it seems he had helped the Americans put a feather in their cap, while killing off one of his master's worst enemies.

By this time, some people in DEA management were beginning to ask questions. The top target for the DEA was supposed to be Chapo Guzmán, and Loya-Castro wasn't doing anything at all on that front. Gaddis, who left the agency in 2011, says he spoke to the agents who handled Loya-Castro and pushed them to get information that would lead to Guzmán. The conversations went like this, Gaddis recalls: "I want you guys to turn up the heat and start having him work more and more effectively against the No. 1 guy." But according to Gaddis, "that never came to fruition."

Double- and triple-dealing is a danger in any spy operation, something to be guarded against. "You should not allow the informant to control you," says John Fernandes, a 27-year veteran of the DEA whose last job was running the San Diego division. "That doesn't mean they won't try. Manipulation is part of life." Still, Fernandes maintains, in general "the DEA does an outstanding job of applying stringent standards."

Gaddis says Loya-Castro did occasionally provide intelligence about the Sinaloa cartel, but not about its top rungs. And at least one internal DEA exchange cited in court documents indicates he was chiefly providing intelligence about the Sinaloa's opposition. Gaddis, who now runs a security company called G-Global Protection Solutions, says he had believed Loya-Castro was a "double agent" the DEA used against Guzmán, but he's now convinced he was more like a "triple agent."

In January, I rode in the back seat of a Policía Municipal de Ciudad Juárez truck, a twin-cab Ford F-150, to see how police patrol one of the most dangerous cities in the world. The drug business, like real estate, is all about location, and Ciudad Juárez is the drug trade's Park Avenue. It is the gateway from which marijuana, cocaine, and industrial-grade meth move across the border and get loaded onto trucks that travel west or east along I-10, or north along I-85. The scale of the brutality in Ciudad Juárez has been obscene: beheadings, massacres, bodies left in oil drums. But now the city is quieter. During the police patrol, only a few people were out and about. Prostitutes posed in doorways along empty sidewalks, their heads turning to follow the police truck as we passed, red and blue lights flashing.

Chapo Guzmán made his move to wrest control of Ciudad Juárez from the local cartel roughly six years ago, and he did so with help. He eventually hired local police captain Manuel Fierro Méndez, who has since been sentenced to 27 years in a U.S. prison. Fierro Méndez was also one of the informants Guzmán planted in U.S. law enforcement. We know this because Fierro Méndez would later testify in U.S. federal court, as a prosecution witness, that he was sent by the cartel to the ICE office in El Paso to give up specific intelligence about the men Guzmán was trying to eliminate.

"You were on a mission from Chapo to come provide information, correct?" he was asked in court in 2010. "Yes," he replied. Fierro Méndez said he was like a "spokesperson," passing information to ICE from Chapo, "information we would, obviously, get from the levels high up."

"Was the Sinaloa cartel trying to use ICE to eliminate its rivals in La Linea?" a prosecutor asked. "That's right," Fierro Méndez replied. "And was Chapo Guzmán aware?" came the question. "That's right," said the former police officer.

He made it plain that that the cartel strictly forbade him to give up anything about the Sinaloa cartel, however. "Were you allowed to give information about Chapo?" "It wasn't allowed," the dirty cop said, "and it wasn't asked of me." In other words, he testified, the ICE agents he spoke to never required him to provide intelligence about the boss of his own criminal organization.

Such information did lead to significant drug busts, which helps explain why American agents were so eager to play along. The costs, however, are clear. "Now the Sinaloa cartel understands how you work, who your agents are, and what you want," says the University of Texas's Payan. "They are using you, and in the end that particular cartel is going to come out of it strong. The Sinaloa cartel is not only virtually untouched but it is magnified ... They don't have any Mexican competition. At home, they are king."

In all, at least five important figures in the Sinaloa car-tel traipsed into the ICE offices in El Paso to relay infor-mation about the Juárez cartel. They provided tips about warehouses, drug routes, murders. They gave up information on who their enemies bribed and what their organizational charts were. And now, as Payan says, "the Juárez cartel is practically down to ashes, and to a large extent it was done with intelligence passed on by the Sinaloa cartel."

A federal prosecutor based in San Antonio who has tried cases against some Sinaloa-cartel members, including those who helped ICE, concurs on that point. I asked him if the information campaign by Chapo Guzmán helped the Sinaloa cartel take over Juárez. "It did," he said. "That's what this was all about: because of the intensity of the struggle, they were trying to exploit every possible thing they could to get the upper hand."

In a case ongoing in federal court in Chicago, lawyers for a top Sinaloa-cartel figure maintain that the DEA's relationship with Guzmán's lawyer was a virtual conspiracy to allow the Sinaloa cartel free rein. Arguing in front of the judge, one lawyer insisted that "this fellow Loya is not a normal informant. He's an agent. He's an agent for the Sinaloa cartel."

Reached by phone, DEA agent Castanon declined to discuss the Loya-Castro case. DEA headquarters also said it could not comment. David Gaddis, the DEA official who oversaw Mexico operations, doesn't dispute that the Sinaloa cartel may have been playing the DEA, but he says there was never any deal to cooperate: "I will categorically deny that at any point DEA was protecting the behavior of Chapo Guzmán." With an investigation underway by ICE into the behavior of its agents in Ciudad Juárez, more details may soon emerge.

No spy story is simple. Nor are the Mexican cartel wars. Though unfathomable violence still flares up in much of Mexico, Ciudad Juárez is somewhat calm. So did a brutal Sinaloa victory over its rivals—achieved, it seems, with the unwitting help of U.S. agents—bring about a lull in the violence in this terrorized border town? If so, few believe it will last.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.