Nearly a year to the day 15-year-old Jenny Fry took her own life, her mother, Debra, brought tulips and a sunflower to lay at her grave.

"In the early days, I came every day," Fry, a dental nurse, says over the phone from her home in Oxfordshire, England, before she left with her husband, Charles, for the cemetery. "Then it went to every other day. Generally, now it's every three days; five days at the most."

She sighs. She sounds drained, unsurprising for a mother still coming to terms with the loss of her middle child. But her exhaustion is not just because of grief. In the year since her family lost their daughter, Fry has devoted her life to battling what she says was the direct cause of Jenny's death: the onward march of technology. In doing so, she's thrust herself into a deeply polarized scientific debate over how best to define an illness on the frontier of science today.

For over two and a half years, Jenny had been feeling ill, complaining of headaches and exhaustion. She couldn't concentrate at school and couldn't sleep at night. Her parents tried a host of solutions to alleviate the problem: They bought a new mattress and thicker curtains to help her sleep; they took her to an orthodontist to see if the headaches were caused by an overbite. "I did all the things you would do in my professional capacity," Debra says, "going through things like a detective to see what caused this or that, and ruling out options."

In May 2015, Jenny came down the stairs pinching her nose. She found her mother and told her that her nose had started bleeding while she was doing her homework. "She said, 'I can't stop it,'" recalls Debra. "'I haven't picked my nose; I haven't banged it,' she told me. 'I haven't had this before, Mum.'" Debra stanched her daughter's bleeding, then took to Google in search of an answer.

She became convinced Jenny suffered from a little-known and highly disputed medical condition called electromagnetic hypersensitivity (EHS). The disease is purported to be a weakness to the electromagnetic waves produced by Wi-Fi routers and cellphone towers. People who believe this say modern society is bombarding us with damaging waves, causing myriad symptoms, from headaches and nausea to nosebleeds and sleep problems.

Debra tore out the Wi-Fi in her family home, replacing it with wired Ethernet connections, and pleaded with Jenny's school to do the same. But it didn't: The headmaster did his own research and came to a different conclusion, pointing to studies that showed there was no link between Wi-Fi signals and illness. Jenny continued to suffer, returning home from school with splitting headaches that would dissipate at home. On a June day in 2015, she killed herself.

At an inquest into her daughter's death, Debra told the coroner, "I believe that wi-fi killed my daughter."

Scientific Dismissals

For the better part of a decade, two diametrically opposed sides—one that claims there is no scientific link between exposure to Wi-Fi signals and illness and another that says people suffer daily because of it—have battled on websites, in newspapers and in scientific journals. James Rubin of the Institute of Psychiatry at King's College London, doesn't dispute that EHS sufferers are ill. "They have physical symptoms; the quality of life they have can be appalling sometimes; they're in desperate need of help," he says. But his surveys of the science led him to believe exposure to electromagnetic rays is not to blame.

Others, including some professionals, disagree. "Ten years ago, I thought this was hokum," says Dr. David Carpenter, director of the Institute for Health and the Environment at the University of Albany in New York. "People have symptoms they want to blame on something, so they come to electromagnetic fields as the source." But that changed with the sheer number of people who came calling at his door, claiming their lives had been irreparably changed by electromagnetic fields. He's now switched sides: He has a sympathetic ear and is banging the drum for those affected. EHS is real, Carpenter says, and it's a problem. "The question in my mind is: How does one—in a rigorous scientific fashion—go about getting information that would be convincing to a skeptical scientific community?"

There have been many attempts. A battery of tests, carried out by researchers in fields ranging from psychology to oncology, have been conducted in the past 30 years to prove EHS is caused by direct exposure to electromagnetic radiation. Typically, the tests involve exposing subjects to electromagnetic signals for a short period and measuring their reaction; then doing the same with a placebo. The results are mixed, but mostly the tests find that subjects can't distinguish between real and fake signals.

(Proponents of EHS take issue with these efforts: Carpenter says such studies "are done in half-assed fashion." Testing 15-minute exposures to electromagnetic fields, he argues, is a poor way to disprove what are in his belief the debilitating effects of prolonged daily exposure to wi-fi.)

In 2004, Dr. Lena Hillert of the Institute of Environmental Medicine at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden presented a seminal World Health Organization report arguing there was no proof EHS existed in the form its sufferers claim. Twelve years on, she says, there's still no scientific evidence for it. "You can never prove that something does not exist," says Hillert, "but if you fail time after time to prove that something does exist, you do kind of say, 'Enough is enough. If we don't have any new ideas or approaches, we should accept that we can't find support for this hypothesis.'" Hillert says that the best current research supports the hypothesis that EHS is basically due to the "nocebo effect"—where the expectation that something will make you ill becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Most of the scientific community agrees.

That's why there are no good data on how many people could be affected by EHS. Though provocation studies continue, EHS censuses stopped in the mid-2000s, before wi-fi became ubiquitous. One estimate presented at a European Economic and Social Committee public hearing in 2014 (not peer-reviewed) suggests that around 5 percent of all Europeans are susceptible. More rigorous (but significantly older) surveys cite similar figures: 3.2 percent of Californians, 9 percent of Germans and 5 percent of the Swiss population complained of symptoms believed to be caused by EHS.

Those numbers might be why the illness is recognized by government officials in some countries. Last year, a judge in Toulouse, France, awarded a woman a disability grant of about $900 a month after she claimed she was allergic to Wi-Fi and therefore could not work. In 2013, an Australian scientist won a workers' compensation appeal for EHS. The Swedish government classifies EHS as a functional impairment, granting compensation for its effects while not making any official judgment on the cause of EHS symptoms. In Austria, there are formal guidelines on how to diagnose and treat illnesses caused by electromagnetic sensitivity.

Fleeing Modern Society

Nevertheless, for those who think controls on Wi-Fi routers are the only answer to the spread of EHS, the web of wireless internet being spun across the globe is worrying. It's impossible to walk through the commercial district of any developed city in the world without your phone pinging up offers to connect to Wi-Fi routers. Wi-Fi is so widespread—it's often free, in stores, restaurants, bars, buses and cafés—that it has nearly reached the status of a public utility. For most of the world's population, that's a boon: instant connectivity, often free at the point of access, to nearly all of civilization's information (and pornography) on demand.

But people who believe Wi-Fi is a public health threat find this an intolerable, a creeping, permanently present menace. As the result of her tragedy, Debra Fry has made connections with a number of activist groups, including Electrosensitivity U.K., trying to slow the spread of Wi-Fi; some focus specifically on countering the rollout of Wi-Fi in schools. "This could be the biggest mistake we've ever, ever made," she says.

Some of those stricken with EHS end up fleeing modern society. The day before I spoke to Carpenter, he had been visited at his office by an attorney who thought she suffered from a form of EHS. Dafna Tachover, who runs an advocacy group for those suffering from the aftermath of EHS, used to work and live in New York City but moved to the Catskill Mountains, 150 miles outside the city. It's the only way to escape, she says, having tried different ways to shield herself from the radiation for several years, including sleeping in her car. "I understood if I wanted to get better," she says, "my only strategy was to avoid it."

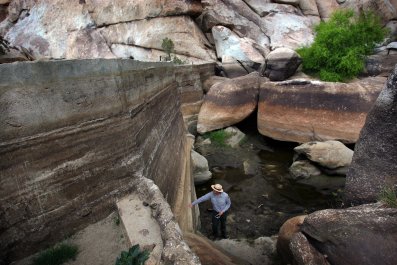

She's far from alone—as more EHS sufferers decide to leave the Wi-Fi world, communities are cropping up out in the country. There is an independently run "EHS refuge zone" in Drôme, France, nestled deep inside a nature reserve, where electromagnetic radiation emitters are banned, keeping background levels down to 1 or 2 microwatts per square meter. Green Bank, West Virginia, has become an adopted home for some EHS sufferers because of its location in the National Radio Quiet Zone, where all kinds of radio signals are banned to prevent interference with the nearby National Radio Astronomy Observatory. An EHS sufferer in South Africa runs an EHS-friendly farm, with accommodations, in the Western Cape. A smattering of similar communities and communes dot the globe.

Carpenter says that EHS today is in the same position as illnesses like chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia and Gulf War sickness were before being accepted by science. "For none of those diseases do you have a blood test that will allow you to diagnose definitively what is wrong. In the meanwhile, the people who have this syndrome are really abused by society," he says. "Are we going to accommodate people that have this rather unusual syndrome, or is it just up to them to find a remote place they can survive without being ill all the time?"

Rubin, who does not think that EHS is real, agrees. "We've spent an awful lot of time and money testing whether electromagnetic fields cause symptoms. And what we haven't done is work out how we can treat these patients," he says.

EHS sufferers often say that if only everyone could see Wi-Fi, pulsing and throbbing across boulevards and down highways, zipping out of storefronts and around corners, they'd understand. Fry carries a meter that measures the strength of such signals. It's small and inconspicuous, and people often mistake it for a cellphone. "In the average busy McDonald's or Caffé Nero," she says, "if everybody is on their laptops and mobile devices, my meter goes off the scale."