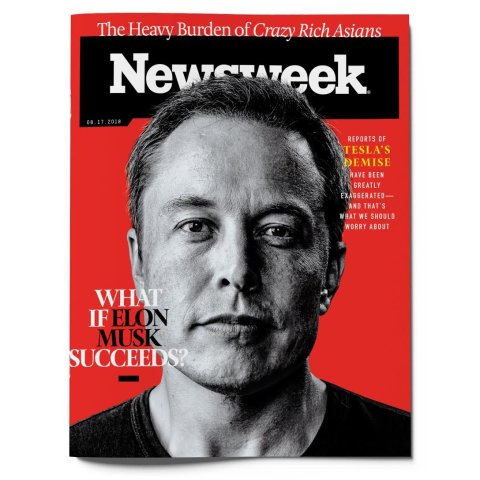

Elon Musk wants to save the planet, and in July that meant a boys' soccer team trapped in a flooded cave in Thailand. One diver had died on the treacherous route, and as monsoons approached and oxygen dwindled, time was running out.

Musk tweeted solutions—perhaps a nylon tube inflated like "a bouncy castle" could "create an air tunnel underwater." The tech billionaire sent 10 engineers to Thailand; he traveled to the cave himself; he posted video of teams from SpaceX and the Boring Company (two of his businesses developing a "tiny, kid-size submarine" and delivered the vessel to the scene.

But the rescuers, rejecting the invention as impractical, developed a Musk-free plan to save all 12 boys and their coach. British diver Vern Unsworth, who played a key role in the rescue, dismissed the mogul's efforts as a "PR stunt," telling CNN that Musk could "stick his submarine where it hurts."

Musk snapped. He inexplicably called Unsworth a "pedo guy"—as in pedophile—and then doubled down amid a Twitter backlash. "Bet ya a signed dollar it's true," he wrote, with no evidence.

Musk later took back the unfounded accusation and apologized. But he's making a habit of being shocking. Tuesday afternoon he tweeted that he was ready to take publicly held Telsa private, having secured funding that would buy back outstanding shares of stock at $420—a 15 percent premium over its then-price of $366. The stock quickly climbed but trading had to be halted as everyone from investors to the SEC tried to figure out if the Tweet was a weed joke (given the 420 reference), a potentially illegal effort to manipulate stock price, or a genuine financial disclosure of unheard-of magnitude and form.

Am considering taking Tesla private at $420. Funding secured.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) August 7, 2018

During a conference call with Wall Street investment analysts in May, Musk, who declined to be interviewed for this story, had refused to answer basic questions about Tesla's faltering financial prospects. "Boring, bonehead questions are not cool," he said. Investors responded by lopping 5.6 percent off his company's stock price the next day.

A few months before, Musk treated his 22 million Twitter followers to harassing rants against reporters who published critical pieces about Tesla, accusing them of bias, conflicts of interest and outright fabrications—also without evidence. He threatened to start a news site that evaluates the accuracy of news articles, tentatively called Pravda—the Russian word for "truth," but better known as the propaganda newspaper of the Communist Party in the former Soviet Union, and now of Russia.

Critics and allies alike began asking: What happened to Elon Musk, the hero of Silicon Valley, the high-tech visionary who was going to save the planet with electric vehicles?

But if you're focusing on Musk's "bad manners," as he called his meltdown, you're missing the point. His plan to transform the car industry is picking up speed. Along the way, it could put tens of millions of people out of work (and that's not a bug, it's a feature), dismantling what has been a foundation of the nation's social and economic life for a century. And it's happening in the service of plying the wealthy with cooler cars.

"Technological innovation has throughout history increased total wealth," says Ryan Lackey, a founder of cybersecurity company ResetSecurity and a veteran Silicon Valley entrepreneur. "But it's often said the gains are going to a smaller and smaller subset of the population."

So the worrisome future may be one not where Musk fails but where he succeeds.

'What the Future Looks Like'

"There's a savior mentality in Silicon Valley," says Lucie Greene, worldwide director of the Innovation Group at advertising and marketing giant J. Walter Thompson and author of the forthcoming book Silicon States, about the growing influence of high-tech companies. "Because these companies can attract so much money despite not having to succeed by traditional metrics like profitability, they're able to position themselves to define what the future looks like."

For Musk, that means transforming the auto industry through innovative manufacturing built around leading-edge robots, advances in batteries and a unique approach to sales that cuts out the need for car dealerships. Tesla has almost single-handedly energized the electric car industry by bringing out sleek, fast, luxurious vehicles that can travel over 300 miles between charges—a welcome development on a planet devastated by our over-reliance on fossil fuels.

Tesla's revenues are climbing as shipments of its first mass-market model start to take off. The company has already taken deposits on the car from half a million apparently eager buyers, and Musk announced in August that Tesla is poised to turn a profit for the first time in the next six months. There's a consensus among analysts that should Tesla burn through the nearly $2 billion it still has on hand—the company incinerated a billion dollars in the first quarter of 2018 alone—Musk can raise the funding he needs to keep going, in part because Tesla may have already become too big to fail.

"The company has a market value of $60 billion, so investors will give him more money," says Colin Rusch, lead analyst on sustainable energy for Wall Street investment company Oppenheimer. Even with the beating Tesla stock has taken recently, the company is still worth more than Ford.

To be sure, high-tech companies have long boasted of disrupting industries with innovative products and new ways to do business. They've unleashed vast improvements in information access, communications and productivity while creating incredible wealth for investors, entrepreneurs and key employees. What Musk represents is the problematic Silicon Valley Effect—the troubling contradiction between tech companies' loudly proclaimed dedication to making the world a better place and their quieter dedication to making products for the rich at the expense of workers.

Just as Amazon's rise has been a disaster for many of the 12 million American workers in the retail industry, Tesla's ascendance could decimate U.S. manufacturing—and not just the automobile industry, which at last count employed 7 million people and supports the livelihood of many millions more.

The catch to building world-changing companies, of course, is that they eventually have to turn a profit. That pressure to make money tends to push even leading-edge companies to focus on those who can afford premium, higher-priced products, and to slash labor costs through automation and squeezing fewer workers to do more for lower wages. Tesla is not exempt from the laws of financial gravity. The cheapest vehicle that the company will currently accept an order for is a $49,000 version of its newest model, the Model 3—a car Musk has long bragged would have a starting price of $35,000. That's essentially the average price for a new car in the U.S., but there are plenty of models priced under $20,000.

His disputed claim—that Tesla can make money selling a $35,000 car to millions of people—has come to sound like the practice Silicon Valley fondly calls "fake it till you make it." That is, a disruptive new company that has a lot of kinks to work out needs to drum up a certain amount of hype to pull in the investors, talent and customers it needs to sustain itself while it tries to make a profit. And then it has to figure out how to deliver on that hype before everyone notices.

Musk had a good run of living up to his hype, until his ability to deliver the Model 3 slipped well behind his promises to start shipping in the beginning of 2018. At present, no cheaper Model 3s will be rolling off the assembly lines in the hundreds of thousands anytime soon. And according to some reports, the lower-priced versions won't reach customers until 2020. That's a problem, because most analysts agree Tesla's survival is pegged to its ability to deliver a $35,000 car in big numbers.

Making matters worse, a growing litany of complaints and safety concerns have dogged the company. The much-touted Autopilot driver-assist system has been implicated in several crashes, a few of them serious and one of them fatal. Earlier this year, Consumer Reports rated the Tesla Model 3 one of the worst-braking cars it had ever tested. A software update to the car—which, like Tesla's other models, is available with the Autopilot system—apparently helped, but concerns recently rose again when Tesla dropped a standard factory braking test, apparently to boost lagging production rates. (The company has claimed it thoroughly tests braking in other ways.)

Meanwhile, Tesla's highly regarded top engineer, Doug Field—a former Apple executive considered among the most influential in the valley—left in early July amid the struggle to fix production woes, the latest in a long string of management departures over the past few years. And a former employee has turned whistleblower, alleging Tesla shipped cars with dangerously damaged versions of its potentially highly flammable batteries, drawing a $1 million lawsuit from the company over what it says are false claims. It doesn't help that a federal tax credit that effectively knocked $7,500 off the price of a Tesla is phasing out.

Even some of Tesla's customers, whose loyalty is the stuff of legend—500,000 buyers have plunked down $1,000 deposits on the Tesla 3, sight unseen—may be getting tired of the delays and bad news. One financial analyst estimates that about a quarter of those advance orders have been canceled. Wall Street is growing increasingly dubious as well. Investors have shorted more than 35 million shares of the company's stock—essentially betting the stock price will dive—saddling it with the distinction of being America's most shorted.

The stock price recently spiked 15 percent in one day on a less-grim-than-expected quarterly earnings report that included the company's prediction it will be profitable by year's end. But that still leaves the stock down $35 from mid-September last year. In March, Moody downgraded Tesla's credit rating, flipping the company's outlook from "stable" to "negative."

'Ahead of the Industry'

Musk has amplified the damage by becoming publicly defensive, surly and just plain weird. But for all the bad press and unforced errors, Mr. Teflon and his company still have plenty of fans. "Betting against Tesla is total stupidity," says Trip Chowdhry, managing director of equity research at Global Equities Research. "Show me any company in the world in any industry where people sign up for a $50,000 product without seeing it first. Whether the company makes 5,000 cars a day this month or next quarter doesn't matter; it's still 500 times ahead of the rest of the industry."

Chowdhry notes that Tesla's edge over the electric car competition includes better batteries, efficiency-boosting manufacturing software and the cost advantage of direct sales without dealers or advertising, as well as a national network of high-speed charging stations. Oppenheimer's Rusch has a more mixed view of the company's prospects but agrees it can raise whatever cash it needs to allow it to keep going for at least a few more years.

Musk is lauded for his engineering prowess and vision, for good reason. But his ability to inspire enough confidence to attract massive investment may be his greatest advantage over major competitors. "If Mercedes-Benz owned Tesla, the board would get impatient and pull the plug on it after it spent a few billion dollars," says Noah Kindler, an executive at hot Silicon Valley electric vehicle startup Evelozcity.

And there are competitors. Jaguar Land Rover, owned by India's Tata Motors, is about to roll out the Jaguar I-Pace, an electric luxury-performance car that early reviewers suggest may be a real contender in the high-end electric vehicle market. Volvo's hybrid and electric vehicle division, called Polestar, has also reportedly been readying an impressive all-electric car. Still, none has come close to garnering the attention and excitement of Tesla products.

Sales of the company's luxury models look solid: It delivered 50,000 of its pricey Models S (starting MSRP: $74,500) and X ($79,500) in the U.S. last year. And when the Model 3 production got off to a rocky start, the company responded at warp speed to fix a raft of manufacturing glitches—Musk led the effort himself (sleeping on the factory floor). It is now producing the Model 3 sedan at an impressive rate of 6,000 a week; the company claims it will deliver 100,000 by the end of this year.

Musk's defenders are confident he'll overcome his current troubles. "Even if Musk can't do it in the time frame he talks about, he'll do it within five years," says Jason Freedman, a highly regarded Silicon Valley insider who just sold his third startup. "People shouldn't pay attention to his debt or schedule; they should just pay attention to the quality of his product. The pace of innovation of a Musk company is way ahead of anyone else."

Tesla recently struck a deal to manufacture 500,000 cars a year within three years in China, the world's largest electric vehicle market. A European plant won't be far behind, the company says.

The High Cost of Success

Even if Musk fails to turn Tesla into a mass-market carmaker, its profits in the luxury market and its many innovations may serve as the catalysts for an ecosystem of new transportation companies and initiatives that will go on to thrive and flesh out his vision for a worldwide conversion to electric vehicles.

"Thanks partly to Elon, the supply chain and consumer acceptance are maturing," says Evelozcity's Kindler. "Because of that, it's a safe bet that electric cars are coming to the masses."

The rub, of course, is that the better things look for Tesla, or companies that pattern themselves after Tesla, the worse they look for the future of American manufacturing jobs. Musk has made clear he's aiming to do away with workers. He's publicly referred to his goal of turning Tesla's factories into "a machine that builds machines," adding that he's going to keep piling on the automation until the assembly line looks like "an alien dreadnought." He promised last year to speed up his production rate by a factor of 20—not by hiring but by doubling the number of robots in his factories to nearly 1,000. According to analysts, Tesla, on average, has already invested twice as much in robots per car produced than other car manufacturers.

And the robots he's buying are far more sophisticated than those you typically find in auto factories, which do the same simple action over and over again. Tesla's bots can be programmed to perform a number of different, more complex tasks, even working together in groups as large as 15 on a single car. It is the first automaker ever to let robots handle final assembly of the cars, a complex set of tasks that is the last bastion of human labor in auto factories. Analysts have pointed out that at the assembly line speeds that Musk has said he's shooting for, the presence of even a single human would be a hindrance, if not an outright hazard.

So far, the effort to hyper-roboticize Tesla's factories has been bumpy. Automation glitches are largely behind some of the big delays in Model 3 production. "Humans are underrated," Musk said after failing to hit targets earlier this year. Which is not to say that there is any chance he will give up on his longer-range goal of eliminating workers. It's no mystery why: Volkswagen has calculated that its robots work for less than $6 an hour, with all costs figured in, compared with $47 an hour in total costs for a human worker.

If Musk succeeds in getting rid of humans in the car factory, he'll likely be able to leverage that achievement, doing the same for the production of the semitrucks he's starting to build, as well as for his already heavily automated battery, solar panel and space ventures (plus any future industry-killer companies that he has yet to dream up). And Tesla's self-driving cars could mean the loss of another layer of employment opportunities: human drivers, a job currently held by roughly 3 percent of the American working population, including 3.5 million truck drivers.

One would think that as high-tech companies excised workers from the economy, they would at least treat those they continue to employ with some consideration. But Silicon Valley's famous table tennis and smoothies perks don't extend to the blue-collar jobs in the region. Reports have detailed how Tesla workers have faced safety risks (including injuries that the company didn't properly report), excessive hours (Red Bulls were reportedly handed out to workers to keep them on their feet) and filthy conditions (some workers allegedly had to move through a raw sewage spill to keep the assembly lines going). The United Auto Workers has accused Tesla of union-busting tactics, and in March the National Labor Relations Board filed a second complaint against the company.

Such erosion of labor standards and job displacement is a concern across all of America's industries, of course. But high-tech companies are making the displacement of humans a central mission and executing it with stunning efficiency. "Silicon Valley could be a big contributor to a manufacturing rebirth in the U.S.," says Chuck Darrah, an anthropology professor at San Jose State University in the heart of valley who studies the region's high-tech industry. "But so much of it now is about automation, and the price of robots in the U.S. is pretty much the same as in China and Mexico."

In other words, labor may be cheaper overseas, but robots aren't, so why not just replace workers with smart machines and build it here?

So where does that leave American workers who lose their jobs? Many of Silicon Valley's successful insiders favor a "universal basic income" scheme, in which the government would send everyone in America a monthly check for around $2,000. "People here understand that if they can't find a solution to the job loss they're causing, they could face a civil uprising," says ResetSecurity's Lackey. "They're so worried about it that they're also buying houses in the middle of nowhere, like New Zealand or Wyoming."

One influencer who has publicly predicted that universal basic income will be the only way out for most of today's workers is Elon Musk. "It's going to be necessary," he reportedly told a conference. "There will be fewer and fewer jobs that a robot cannot do better."

Let's say Silicon Valley's growing influence and success is worth the high cost to worldwide labor. Maybe Musk will ignite a green transportation movement that slows or even halts climate damage—or pave the way for colonies on Mars if the planet is beyond repair. Maybe these high-tech companies really are, as they claim, nurturing the seeds of a better health care system, a healthy food revolution and an education system capable of affordably serving most students—and not just those from affluent communities or those who are academically gifted—all the way through a good college education.

Technological change causes economic and social upheaval—that's a given. We ride it out, hoping for the best. "You must remember that every invention of this kind which is made adds to the general wealth by introducing a new system of greater economy of force. A great invention which facilitates commerce enriches a country just as much as the discovery of vast hoards of gold."

That's Thomas Edison in 1895, telling a skeptical, uneasy public that "the horseless vehicle is the coming wonder."

Human innovation is always in the driver's seat—even if humans won't be.