Earlier on Friday, a suspect was arrested in Salisbury, Maryland, for sending a virtual attack through Twitter to Newsweek senior writer Kurt Eichenwald last December. The suspect, whose name was confirmed by a law enforcement official as John Rivello, sent a GIF of a strobing image to Eichenwald on the social media website that was deliberately intended to trigger a seizure.

The message, sent by an account with the Twitter handle @jew_goldstein, followed Eichenwald's appearance on Tucker Carlson Tonight. Eichenwald has epilepsy, a diagnosis he has spoken about publicly. "You deserve a seizure," the Twitter post containing the image read. The strobe did lead to a seizure, and Eichenwald had vowed to take legal action.

Related: Suspect Arrested, Charged With Causing Writer's Seizure

Despite the apparent ease with which light can trigger a seizure, much about the phenomenon is poorly understood by the average Twitter troll and other nonexperts. The key is electricity, the invisible force that allows our brains to function.

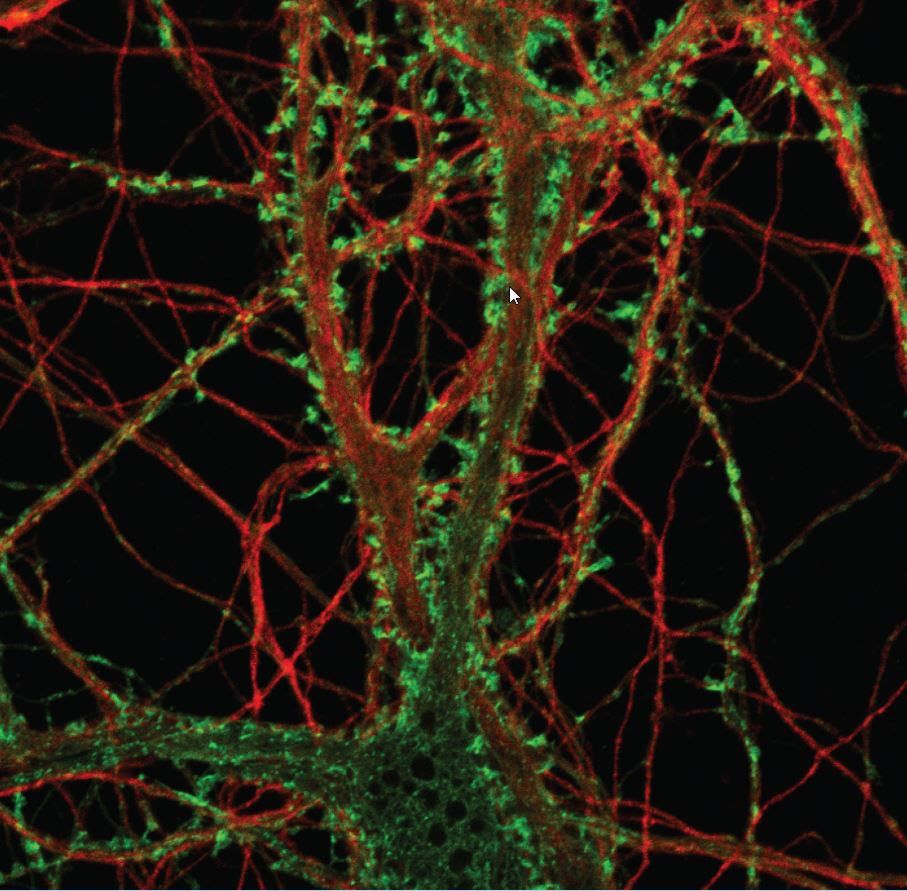

Millions of neurons constantly transmit electrical signals that influence our every move, thought and feeling. The condition called epilepsy renders some people, usually through a genetic predisposition, susceptible to sudden and abnormal discharges of electricity resulting from sensory overload or chemical changes in the body. These changes cause collections of neurons to release a relatively large quantity of electricity all at once, commonly known as a seizure. These bursts are often unpredictable and cannot be controlled while they are happening. An estimated 150,000 people in the U.S. develop this condition each year, making it the fourth most common neurological problem in the country.

In people with photosensitive epilepsy—about 5 percent of all epilepsy cases—light is the seizure-triggering culprit. Specifically, lower wavelengths of light—the flash of a strobe, sunlight flashing intermittently through a picket fence—may trigger seizures. These patterns, says Joseph Sirven, a neurologist with the Mayo Clinic in Arizona, disrupt brain function.

The key is the speed of the flashing. Most photosensitive epileptic seizures are sparked by five to 30 flashes per second. Pulses of light coming at the brain faster do not pose the same danger. The slower the pace, says Sirven, "the more closely it approximates brain function." Although the exact pathway is not clearly understood, this additional electricity entering the brain is converted to a signal that leads to clusters of neurons releasing their electricity all at once.

Sirven explains that the propensity for flashing light to trigger seizures—rather than, say, a strong smell or something touching the skin—may be because the area of the brain that controls vision is confined to the occipital lobe, a discrete area of the brain. The neurons processing information from our other senses, by contrast, are more widely distributed.

A photosensitive seizure does not lead to permanent damage, but a person may experience temporary memory or language loss after one. And a seizure happening while, say, driving could prove very dangerous. People with epilepsy also fear having a seizure in public, an event that could be detrimental socially or professionally. Children may be teased. Interacting with the public as part of a job may worry an employer. "There are consequences," says Sirven. "This is a very stigmatizing condition, and there is no way around it."

Internet imagery is not a specific risk category, but Sirven says he has heard about parents or patients mentioning time spent playing video games or reading material online when they discuss seizures. "It's not uncommon to hear that as an inciting factor," he says. And while the number of people living with photosensitive epilepsy has not changed in recent years, the number of seizures has increased.

"It's hard to know whether people have become more sensitive," Sirven says, "or whether there are more risk factors."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jessica Wapner is the science editor for Newsweek. She works with a talented team of journalists who tackle the full spectrum ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.