Every monument at the National Memorial for Peace and Justice has a duplicate, and the mission of the Equal Justice Initiative is to get all of the over 800 counties implicated in racial terror lynchings to claim their monument. So far, close to 300 counties have expressed interest in doing so. "It's been surprising and encouraging," says Bryan Stevenson, director of EJI. "We're very energized by that."

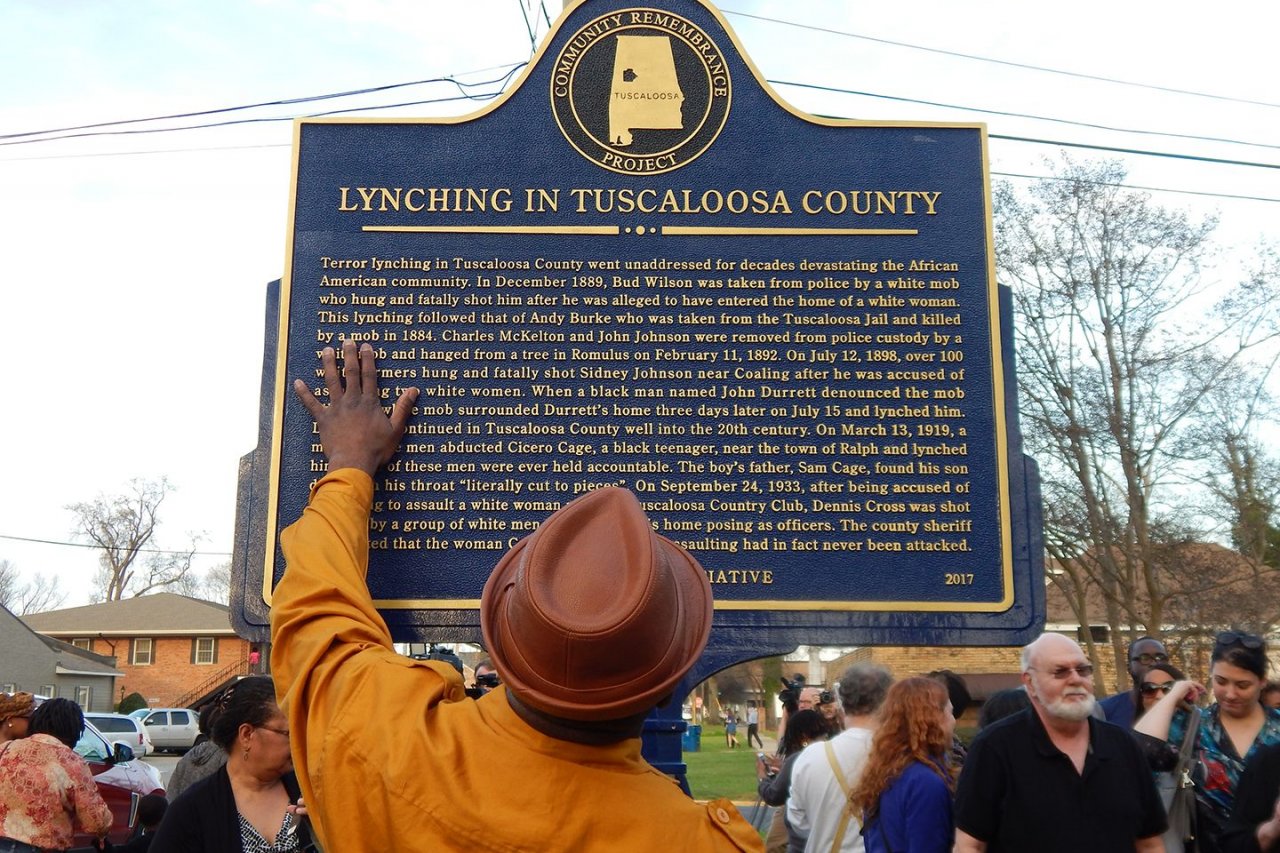

EJI is insisting on a deliberate process to make the event as meaningful as possible. "Everybody wanted to just come grab their monument and say, 'We did that,'" he says. Instead, counties are asked to first erect historical markers for each lynching. "The idea is to build up a consciousness, to truly understand the legacy of lynching before you claim the monument."

That process includes an EJI-sponsored contest for high school students in the community, who are asked to write an essay on racial injustice (the winners receive a scholarship of $3,000.00). At the end of each ceremony, soil is collected from the site of the lynching, part of the nonprofit's Community Remembrance Project.

Since October, EJI has sponsored a ceremony a week in counties in Mississippi, Florida, Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee. On October 27, close to 500 people gathered in Lafayette County, in Oxford, Mississippi, to celebrate the life of Elwood Higginbotham, who was lynched on September 17, 1935. The 28-year-old tenant farmer was hanged by a mob of 50 after he shot his landholder in self-defense. No members of the mob were prosecuted.

RELATED: America is Racist. So what do we do now? Activist lawyer Bryan Stevenson has some answers.

April Grayson, director of community building for the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation, helped organize the event. "There were a total of seven people lynched in the community, and Elwood was the first step in the process," says Grayson, who adds that Lafayette County officials have been very open to claiming their monument. "We only encountered resistance from one business owner, who felt it was stirring up old injuries," she says. "We have the University of Mississippi here, and there's a sizable number of people in the community, elected officials among them, who recognize the value in reckoning with painful histories."

The day of the ceremony, she says, "was a real picture of the wider community," a multiracial crowd that included 40 members of Higginbotham's family, including his son, E.W., who was 4 when his father was lynched. "To publicly say that this act of white supremacy is not what we want to represent our community was healing."

The first public mention of Higginbotham's lynching, since the 1935 event, was in a local newspaper five years ago. "I've lived here for a number of years, and I work along these issues, and I wasn't familiar with any of the history of lynching in Oxford before then," says Grayson. "The [marker ceremony] was the first big public discussion of it. It's impossible to deny the impact racial terror and violence had on African-American families—on their health and their livelihood; they lost land, connection to extended family and opportunity."

The iconography of white supremacy is everywhere in the South. For Grayson's community, the marker and eventual establishment of the monument (expected in 2019) present an important counter to those symbols of segregation. "But I expect many communities won't feel as ours did. For them, a monument would feel like a challenge."

"Healing requires acknowledgment," says the Reverend Iva Carruthers. Communities that are reluctant to claim their monuments, she says, "don't want to acknowledge the harm that was done. If you acknowledge the harm, then you have to acknowledge your complicity with it."

Carruthers attended an October 19 marker ceremony for Anthony Crawford, a 56-year-old planter lynched by a mob in Abbeville County in South Carolina, in 1916; he had argued with a white merchant over the price of cottonseed. No one was prosecuted, and most of the surviving Crawford relatives fled north.

Carruthers was a close friend of Crawford's great-great-granddaughter, the late Doria Johnson, who was instrumental in moving the casket of Emmett Till to the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture. In a show of support, members of Till's family attended the Crawford ceremony. "It was a very high day," says Carruthers, one that included "liturgically dedicating the land, the marker. It included a ritual of celebration and renewal, and a ritual of consecration. This symbol of reckoning," she adds, "is also a symbol of reconstituting the history of this country."

There is always fear of vandalism. In 2016, Till's marker, in Money, Mississippi, was riddled with bullets. Grayson has driven by the Higginbotham marker several times since the ceremony, and so far so good. "It moves me so deeply every time," she says. "A lot of people have reached out to say how grateful they are.

"I think more communities will claim their monuments," she adds, "as people see these markers become examples of positive bridge building and healing." —Additional reporting by Anna Menta

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.