To date, scientists have confirmed the existence of 3,564 planets orbiting distant stars. That number is only ever going to go up, and a new instrument is all ready to do just that, according to its host, the European Southern Observatory.

The instrument's full name is the Echelle Spectrograph for Rocky Exoplanet and Stable Spectroscopic Observations—ESPRESSO for short. It's not so much a telescope itself as a room-sized device that pulls together data from four existing telescopes, creating a much more detailed picture of target stars. That will help the device narrow in on small rocky planets like our own, rather than being limited to less homey gas giants.

Most exoplanets are found by what scientists call the transit method. A telescope stares at an individual star, measuring precisely how much light it is emitting, then looks for slight periodic dips in that light. Those dips suggests that a planet circling the star has blocked a small portion of its light. NASA's Kepler missions, which have single-handedly identified 2,515 exoplanets, use this technique.

But there's a second approach scientists can use to spot these distant worlds, and that's what ESPRESSO is designed to use. The instrument is based on previous devices like the High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher, run by the same group, which recently identified a planet about the size of the Earth that may have a more hospitable star than many other exoplanets.

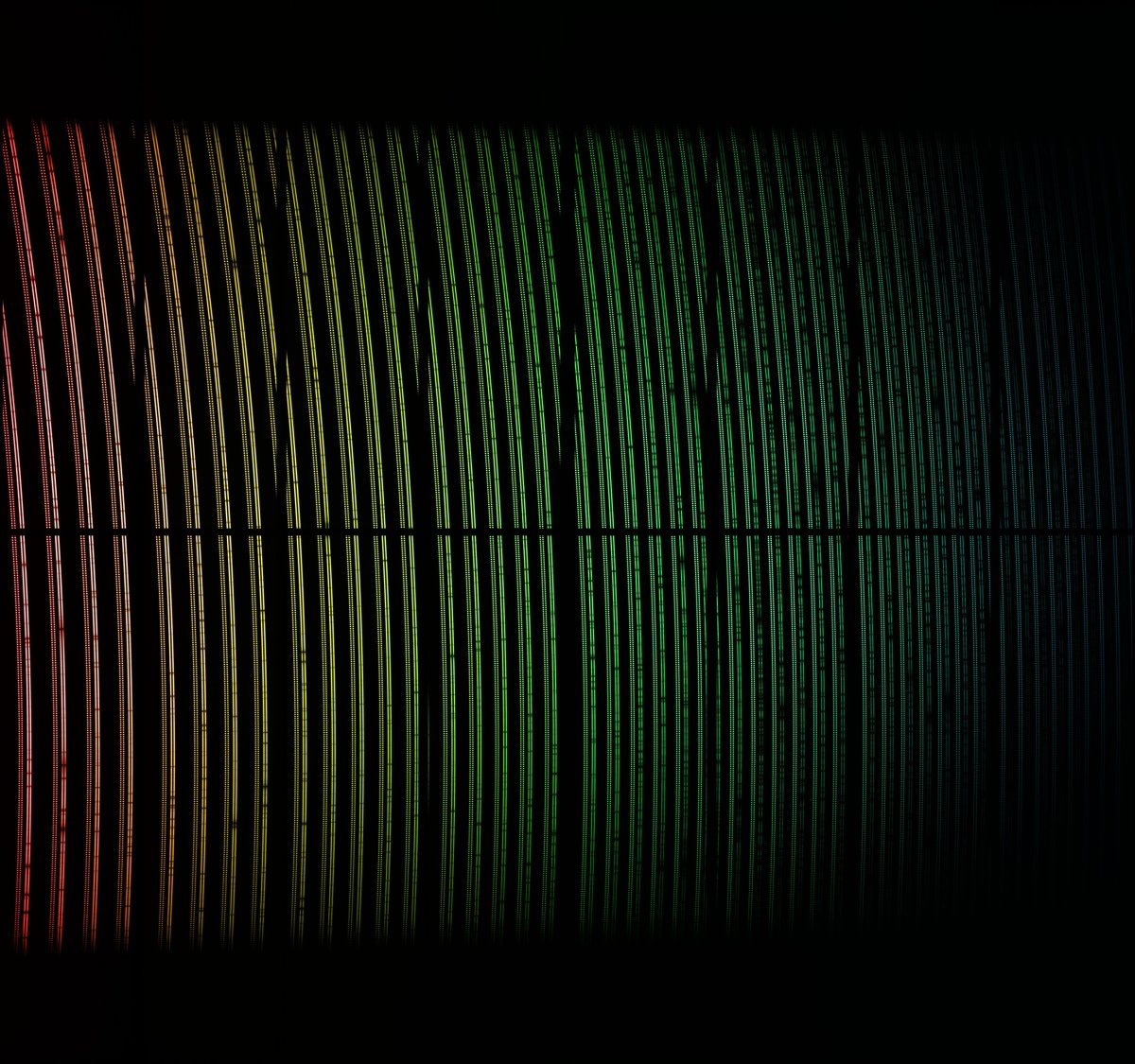

Both of these devices are echelle spectrographs, which take highly detailed measurements of the amount of different types of wavelengths of light coming from stars and planets by sending red and blue light in opposite directions. That, in turn, lets scientists measure tiny wobbles in a star caused by its interaction with a planet's gravity.

ESPRESSO is designed to give the best possible look at quiet medium stars—the stars most like our own sun. So far, more than 500 planets have been spotted using this technique. While ESPRESSO will be focused on its own new finds, it will also investigate possible exoplanets spotted by Kepler and other transit methods.

Related: Ross 128 b: Potentially Habitable Alien Planet is Hurtling Toward Us

In addition to studying exoplanets, ESPRESSO is also designed to help scientists understand whether some of the two dozen traits they currently consider constants are, embarrassingly, not actually quite constant after all, possibly changing a little since the universe's birth.

Last month, scientists working with ESPRESSO tested it against a set of well-studied stars and planets to make sure everything was working properly. Now, they say, it's ready to start doing real science.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Meghan Bartels is a science journalist based in New York City who covers the science happening on the surface of ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.