Under the leadership of Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, Poland has taken a decidedly nationalist turn, winning high praise among many Western conservatives but scorn among some progressives. Like many of its peer countries in the Visegrad Group and the Three Seas Initiative, Poland sits at the crossroads of the Western European/German-centric hub of pro-European Union sentiment to the west, and the broader umbrella of Vladimir Putin-led Russian influence to the east. Poland under Morawiecki is uniquely positioned as both strongly pro-EU and strongly pro-America.

Newsweek Opinion Editor Josh Hammer and Polish-American journalist Matthew Tyrmand sat down in Warsaw with Prime Minister Morawiecki on May 27. A member of the national conservative Law and Justice party, Morawiecki has served as prime minister of the Republic of Poland since December 11, 2017. The following conversation, which has been lightly edited for clarity, is the first in-depth English-language interview with an American news outlet that Morawiecki has done since taking over as prime minister.

In the interview, Morawiecki details at length the challenges facing the European Union, including how to best ensure that it is an earnest geopolitical "superpower" and not a mere "supermarket." He discusses ways to strengthen democracy—an especially acute issue, given the past century's history of Central and Eastern Europe—by looking to former President Ronald Reagan as one shining example. He is critical of the Biden administration's 180-degree turn on the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which will transport natural gas from Russia into the heart of the EU. Indeed, he is critical, more generally, of the Biden administration's energy policy to date. And Morawiecki takes a nuanced position on China, but a decidedly less nuanced position on the drastic 21st-century challenges posed by Big Tech.

Newsweek (Hammer and Tyrmand): Let's start with the economy. The Polish economy has grown steadily, with barely any contractions since 1989. But new challenges threaten the eurozone economies and those challenges have a high correlation to Poland's economic growth. So how do you see Poland economically positioned, more generally, as we start to emerge from the COVID pandemic?

Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki: To be precise, there was a huge contraction between 1989 and 1991—a huge recession. And then, since 1991, there was steady growth until the COVID-19 pandemic and the recession connected with this. However, our drop, our recession was one of the shallowest in the European Union. That is because of very brave usage of "anti-crisis shields," as we call them, a financial shield. This was in the range of 10 to 12 percentage points of GDP, of this size.

We have preserved jobs. We have the lowest unemployment level in the European Union right now. And we have helped companies go through the most difficult times in 2020. And now they have preserved their market share, they have preserved their capacity to expand, capacity to export and we see a very strong recovery right now.

So I'm happy with regard to the prospects of the Polish economy over the next couple of years. It's very well prepared now in this phase, post-COVID, to build on investment—and in particular, exports and domestic consumption as well.

Speaking of the EU and eurozone, we are five years now after the U.K. voted to leave—and fewer years than that since they actually left, obviously. But the fissures in EU cohesion remain and the heavy-handed harmonization efforts out of Brussels continue to catalyze dissent from national electorates in places like Italy, and even as far as Spain. So can the EU get on a track that is more harmonious and encourages more integration among the nations? Or is the post-Brexit political volatility in continental Europe a permanent feature of European continental politics, and these kind of fractures and fissures are going to remain as the post-Brexit dynamic continues to percolate?

It is quite fractured, but I wouldn't say it must be our weakness. If we want Europe to be a superpower, we should not expect that there will be one "United States of Europe" because it will never be exactly, that in my imagination. There are 27 countries, and several more closely aligned that are not belonging to the European Union, but all of which have strong identities, cultural heritages, languages and traditions. But not only this, they are also having their own natures, so to speak. And in accordance with this, this pride and interest, we are stimulating our own growth and we are going toward a future where different countries are oriented toward their different competitive advantages.

So for Europe to be strong, it has to be a "Europe of homelands." It cannot be one superpower, because if that is the case, there will be frictions and tensions that are going to grow even bigger if those from Brussels, Berlin or Paris would try to push all the others toward such a state. But contrary to just simple thinking, I believe that this is the only way for the European Union to be a superpower, rather than just a supermarket for different goods and services.

We must be able to work out a common strategy toward the external world and the global powers—in particular, those in the east, which do jeopardize our development. And in our common relations with the transatlantic community in particular, as well. So for me, it's a different way of looking at the same problem. We can be a superpower, but without this meaning a one-size-fits-all type of philosophy that some Eurocrats from Brussels seem to believe in.

On the other hand, I am a true believer in the European strategy toward external jeopardies from the Muslim world, from China and from Russia. And for this, we need a very strong alliance with the United States, of course.

Focusing more specifically then on Central and Eastern Europe, how do you see the Three Seas Initiative taking shape to become a more potent political and economic counterweight to Western Europe's more historically developed states? And then, as well, the relationship between the Three Seas Initiative members vis-à-vis the foreboding Putin-Russia threat coming out of your eastern flank, as well?

Contrary to some statements about Three Seas from Western Europe, in particular, I do not see Three Seas Initiative as being in opposition to the unity and to the strength of the European Union policy. The opposite is the case, in my view, because it's the "missing lung," as John Paul II said, of Europe. The western lung is on one side, while the eastern lung is not so well developed.

For it to be better developed, we need north-south connectivity—north-south infrastructure, which is missing. In Europe, we have quite well developed east-west interconnectors, in terms of infrastructure, energy, roads, railways and so on. We do not have the same from Scandinavia down to Greece. And for Poland, which happens to be in the middle of this geography and is the biggest country of all these Three Seas countries and potential Three Seas countries, this is a missing link in the strategic and defense architecture—because this [Poland] is at the same time the eastern flank of the European Union and the eastern flank of NATO, and is thus more geographically exposed and at risk.

By developing this [Three Seas Initiative] and supplementing this with that lacking infrastructure, we are going to strengthen the presence of the European Union in the transatlantic community, which is multi-dimensional, in this part of the world. And this is going to make the whole of the European Union and the Transatlantic community stronger. So it's in the interest of the United States, and in the interest of Western Europe, to strengthen this dimension, rather than fighting against it.

Focusing a little bit more on Russia, what can the EU collectively do about Russian encroachment and the Russian threat, both directly through physical sovereign border breaches and also indirectly—cyberwarfare, disinformation campaigns, spy games and so forth? What can the EU do collectively to stand against the Russian threat, more generally?

We have to be consistent and patient with regard to our Russia policy because the stability of Russian strategic policy is a challenge to us and to the European Union, where governments change much more often than in Russia and where there are different views on Russia. The further from the east, the lesser Russia is perceived as a threat. Notwithstanding this, we were able to work out a common view on sanctions toward Russia for occupying the Crimean Peninsula and the Donbas area, on the one hand. On the other hand, we still try to persuade Russia—or more accurately, dissuade Russia—from being aggressive in their own strategic activity. And from our more strategic view, Russia could be one obstacle for China to further grow and expand its influence and power all over the globe. But for this to happen, we would have to have a truly peaceful non-aggressive Russia, which is not so easy to imagine.

And thus, when you asked about the hybrid wars and cyber-attacks and spy wars and so on, this is a real threat. The recent attack in the Czech Republic and the discovered truth of such an attack in Vrbetice, the munitions store in the Czech Republic, just confirms that Russia is not a normal democratic country. (Editor's Note: Morawiecki is referring to the 2014 Vrbetice, Czech Republic ammunition warehouse explosion, which was recently confirmed to be a Russian operation.)

For this to change, there would have to be a strong will at the top of the Russian elite, which I don't believe happens that quickly. What I believe more likely happens is that Russian society will gradually, year after year, be more demanding for true freedom and democracy and rule of law.

What about Russia using its energy and its energy policy vis-à-vis exportation of energy as a weapon, and how that might affect Central and Eastern Europe?

Well, they're certainly using it this way. In Syria and Libya and other parts of the world, it is a very active instrument of their foreign policy. And this is also the area where we try to collectively tame them, in the context of NATO.

But what about Belarus? Belarus obviously is in the news right now, as the post-election situation there has led to an escalation of implicitly Putin-supported muscle-flexing. What are your thoughts on Belarus and President Lukashenko, and Polish policy on Belarus?

Yes. It was quite an unfortunate development in the post-election period of Belarus. Indeed, I truly admire the Belarusian society for their stubborn and patient resistance towards what is happening in Minsk, and in Belarus. Of course, they are all living very much in the shadow of Russia, and this is why this is so complicated because Lukashenko is not only representing Lukashenko himself, he has strong support from Russia.

Having said that, we have quite strongly and collectively condemned the act of hijacking this airplane—which, by the way, was and is registered in Poland. And there was no country, no member state of the European Union, which hesitated on the sanctions upon which we have all agreed to levy during the last European Council meeting. And on the other hand, we have put on hold the help, the pretty handsome aid package of economic and social assistance for Belarus, until there are pro-democratic changes in Belarus because we don't want to strengthen Lukashenko in any way.

It is going to be painful for the Belarusian society, but from what I hear in Belarus today and from what I know very well in my own experience, with the example of Poland during the 1980s, President Reagan's sanction on the Soviet Union, which extended to Poland back then, was very effective because it slowed and decelerated the spread of technology into Russia and the entire Soviet Union.

It was painful from the social point of view, and after several years, the new democratic attempts started during the Round Table Talks and they've proven to be quite successful. [Editor's Note: Polish Round Table Talks took place in February to April 1989, and the then-ruling communists agreed to new power-sharing and a road map to free elections.] So I just hope for a similar evolution in Belarus, with hopes that this is going to happen more quickly than over the next five or six years, as it took in Poland between 1982-83 and 1988-89.

Let's go back for a second, then, to energy and Nord Stream 2. A lot of U.S. conservatives are somewhere between surprised and just enraged that President Biden has signed off on this while simultaneously blocking the Keystone XL pipeline running from Canada to the U.S. at home. It doesn't make a lot of sense to us in the U.S.

So from Poland's perspective, what can and should be done about this end-around of Central Europe's energy security? It seems like Germany has made kind of a Faustian bargain with Russia at the same time that it's leading a charge for more Europe through devolution of sovereign power toward Brussels, more integration in policymaking and more acting in harmony out of collective self-interest. So what can be done about Nord Stream 2, in particular, which flies in the face of those stated ideals and goals?

We are very disappointed, in Poland, about the recent change of the position of the United States in particular because, over the last couple of years, we have worked hand-in-hand with the U.S. administration to stop or to slow down the development of Nord Stream 2. And it was only recently where the American administration changed their view on this with false hopes that this will help to repair the relations between the U.S. and the European Union. Well, Germany is not the European Union. Germany is Germany, and they have their own interests and it happened that their interests are quite aligned and on the same page with the Russian interests.

But this is not aligned with the transatlantic interests. So Germany is on the collision course with the transatlantic strategy, in that view, regarding its own energy interests. And by this, I don't only mean importing American gas, through which the president of the United States lessens or reduces the chances of doing so, in the U.S. exportation of American shale gas into Europe. That's not really the primary significance here. The primary significance is that by stopping Nord Stream 2, we were trying to not help the Russians accumulate funds for their military developments and aggressive policy. And it was quite successful until very recently. So such a change was very disappointing, and not only for Poland but for many European countries.

Have you or has the Polish government been in direct contact with the Biden administration, to express your disappointment about these developments in particular?

Yes. We've expressed our disappointment quite publicly.

What do you think the Biden administration's motivation for this possibly was? It's a turning of the Trump administration's policy on this issue on its head. And it particularly stands out because this 180-degree turn happened after talking so tough on Russia—at least, rhetorically—and signaling a commitment to a strong transatlantic U.S./pan-European relations. What do you think is motivating the Biden administration to do this?

I think a very simplistic—too simplistic—analysis of the European Union and hopes for repairing relationships with the European Union through Germany. But Poland is much more active, in terms of defending the eastern flank of the European Union—which is, at the same time, the eastern flank of NATO. And also, Poland is probably the only such society and nation in the whole of Europe which is at the same time pretty fully pro-European and pro-American. So we are a natural keystone integrating these two dimensions, which is very important from the point of view of psychology in politics, as well as with the economy. So it was to the detriment of deeper transatlantic unity what has just happened, that now Russia is going to get a strong instrument in their hands to further divide transatlantic interests and to use its weaponry toward Ukraine and Belarus overtly and covertly. Nothing is going to stop them [Russia] now marching deeper into Ukraine, because their gas pipeline system—I mean the Ukrainian one—is going to be redundant pretty soon after the Nord Stream 2 pipeline is completely established and fully operational.

So what is Poland's plan, looking ahead for raw energy—oil and gas sourcing? Is it going to continue to purchase from American producers and bring that in via the Baltic terminal? Are there plans to expand that capacity to perhaps become a re-exporter to other Three Seas nations or other local and at-risk allies?

Yes. We now have our domestic demands just below 20 billion cubic meters. For the next seven years, we forecast another seven billion cubic meters of domestic demand for gas. We have four and a half billion cubic meters of domestic production and we are soon going to have seven and a half billion cubic meters of terminal capacity in the Baltic Sea, and in 12 months' time, we are going to establish where to finalize works on the Baltic pipeline to the Norwegian shelf. This, together with the floating terminal near Gdansk of up to five billion cubic meter capacity, is going to be more than sufficient for Poland. We are concerned about the problems resulting from the suspension of the construction of the Baltic Pipe on the Danish part of the gas pipeline. However, I hope that these are temporary difficulties that we will overcome for Europe's energy security.

So from our point of view, we are going to be independent of Russian blackmail for the first time in our history, and this gun to our head no longer exists in terms of the pricing pressures or threats of closing the tap of gas at whatever entry point into Poland. This is not just about the security of the gas supplies into Poland—it's about much more than this. It's about the integration and common strategy of the transatlantic community vis-à-vis Russia. And this has been put under question by the 180-degree change of policy that just happened by the American administration.

One final question on energy. At the same time that the Biden administration is waiving sanctions on Nord Stream 2, it's cracking down on domestic energy production with respect to drilling on federally owned land, with respect to the Keystone XL pipeline and so forth. So is Poland worried at all about how Biden's domestic actions might lead to dramatic fluctuations in the global prices of oil and natural gas? Is that something that you're particularly concerned about?

We are looking at all the changes and evolutions with high attention, and we are very concerned about these changes. Also, from the point of view of the recent developments in the price evolution of oil and gas in the world, America is signaling its reduction of its strategic interest in this sector.

Let's put it like this: The United States started to be the critical point of oil production just two or three years ago—now even more important a player than Saudi Arabia. And I prefer very much to be under such an umbrella, which is good for the U.S. and is good for the entire globe—it's good for the democratic planet not to be in the hands of the Russians, OPEC and the Arab producers. So by depriving America of this very tool, I think we collectively in the transatlantic community are going to be weakened because the dictators and autocratic regimes, such as many in the Middle East and the Russians and some others, are going to dictate prices. And they will have more money for terrorist activity in the Muslim world, they will have more money for more aggressive military policy and we will be paying more. So our economic growth is going to be weakened.

Coming back toward the broader economic discussion—some political economists refer to Poland as a "nation of shopkeepers," emphasizing small businesses as where the vast majority of Polish GDP is generated. How does Poland continue to foster the creation of deeper pools of capital and the evolution toward larger enterprises to expand GDP? How does Poland, with bigger firms, create more jobs over the longer run and eventually raise the living standards of more citizens, especially those outside the largest cities? Is the Polish government currently recruiting more large-scale foreign direct investment (FDI)? Are there any specific regulatory steps or incentives that your government is doing to foster more capital coming into the country, with these goals in mind?

That's a very valid point because we are to a large degree a country and nation of small- and mid-sized enterprises. And even by Western European standards, our champions are mid-sized companies. And accumulation of capital is therefore more difficult than in many other circumstances.

So there are several routes through which we are going to improve our position from the capital accumulation options point of view. One goal we are working toward is to push our mid-sized companies to be bigger through exports and finding new markets for our companies. Our export policy is in export promotion and pushing our larger enterprises to become Polish champions and also European champions. And also through M&A activities, where we were able to promote this policy with our public companies—and at the same time, our private companies are doing a very good job in this regard, as well. They are more and more often buying their competitors in Western Europe. This is a phenomenon of the last five years, whereas it was very rarely happening before this recent era. And now it's made easier because of our policy to utilize the Polish Development Fund, which is helping these firms with potential and ambition to expand to move toward foreign expansion and an internationalization of their business, so to speak.

In Poland, there are many small- to mid-sized companies that even today are too big for just Polish activity, but they are still too small to compete with the biggest players in their industries in the globalized commercial world. But they are quite appropriate in size to go and compete at a high level on the European stage. So that's one area of our policy in trying to help guide the successful evolution of our competitive private sector enterprises.

Another one is in attracting foreign direct investments in a model similar to Singapore or South Korea. We have created very attractive conditions for technologically advanced foreign companies in different phases of the production. Beginning with research and development, there's a very attractive tax system for those who want to innovate here. I won't dwell too deep into the details unless you want me to, but that's a special package for research and development. And over the last two years, research and development went through the roof to a level never experienced before in our history.

Then we have prototyping, and for prototypes, it's a special set of incentives as well. Then you have beneficial tax structures—for instance, for intellectual property, there are special tax breaks of 5 percent for this type of production related to high value-added products or services. A 5 percent rate is one of the lowest in Europe for this type of activity. And then we have something we call Estonian CIT (C-I-T being the corporate income tax). This type of corporate income tax means that until you recoup your invested money, you're not paying taxes at all. So, zero tax if you do not take your money outside of your company and you continue to reinvest it. You can invest as much as you want and all your profits are not taxed. So this model was proven to be very successful in creating a new industry from scratch, like the electric batteries industry or electric buses—Poland is today the biggest exporter and the biggest producer of electric batteries and electric buses in all of Europe. So we are attracting lots of FDI in these growth industries.

And the third element of accumulating capital was through repairing our fiscal system, our financial system, which was an Achilles heel of Poland for many decades, if not always. We have repaired this, and we were able to provide society with a very generous social policy, having at the same time close to zero budget deficit. Pre-COVID-19, we were able to lower our public debt-to-GDP ratio. And on top of all of this, we were able to accumulate capital for unprecedented public investment—for example for roads, for modernizing railways and so on.

There is even more money from our domestic sources for those investments than from the EU budget. [Editor's Note: Poland is the EU's largest recipient of infrastructure funds from the EU common budget.] And if you asked anybody five or 10 years ago if such a development as this would be possible, I think nobody would agree. Now we are much more independent from EU funds and are able at the same time to accumulate an appropriate amount of money for our own domestic investment.

How did you accomplish one of the European Union's leading progressive social policies with the 500-Plus program (stipends for growing families), the housing policy as in building more affordable housing units as a public program in order to get more people into apartments and so forth without creating a budget deficit?

This was really in particular through applying very modern IT tools in our Ministry for Finance. This was using artificial intelligence and machine learning type of algorithms, which we have then implemented across the board in terms of our tax offices. So it required some training and development of IT, and we have then applied this to the whole system. So not only were we able to dramatically increase tax receipts, but at the same time we have lowered tax rates for businesses. Like for the small- and mid-sized businesses, it's 9 percent, the tax rate. For personal income tax, we have lowered the rate from 18 percent to 17 percent, and now we are going to have a higher tax-free allowance—one of the highest tax-free allowances in all of Europe. This goes hand-in-hand with repairing the fiscal system, which was very much in trouble before.

Shifting gears to the regulatory framework and specifically one area that has become a critically important debate in both the U.S. and the EU—Big Tech. Poland has really led the way here in the last several months. The Polish government, your government, has come out drafting legislation that would impose punitive financial penalties on these globally active American Big Tech and social media firms for censorship that would breach domestic law or the Polish Constitution, which is a constitution committed to free speech ideals. What is the current status of this legislation? When do you expect we might see enforcement occur, given that the censorship has, if anything, accelerated—and those who are not politically aligned with Big Tech are often still purged, banned, censored and de-platformed? The risk this poses to a free and plural society is not going away.

Well today, who sets these rules is really the master of destiny for society and for nation-states. So today, platforms and communication networks and intellectual property are even more important than the land and the buildings and the technology assembly lines and all the materials that go into creating these digital realms. And these dynamics do not make it easier to grasp the elements of the moving parts of the complicated interdependent economic jigsaw puzzle that is our modern age. And this is why it is so much more difficult to understand who sets the rules today, because it is no longer the governments that can have this competence over the setting of the rules. Huge international corporations in the area of the digital world, in particular, are setting the rules very often that are suitable for themselves, which may not always be a social good. This is another form of dominance over the rest of the sectors they operate in, but it may also create dominance over other areas of the lives of citizens in a society. And this is why states should now be very active in eliminating censorship and eliminating monopolistic powers of those companies, as well. And this is one of the reasons we started to work on this anti-censorship regulation.

And this is still being cooked in the Polish parliament, by the Polish government working through the domestic legislature, but we are quite determined for this to work—either together with Brussels, or on our own to go ahead with this if need be. We are in discussion with the European Commission in two aspects of this area. One is vis-à-vis the freedom of speech and eliminating censorship issue. The other one is in taxing companies where they do business—so not letting them go to tax havens like Luxembourg or Cyprus or Switzerland, and not paying taxes at all or very little taxes paid in these other tax haven countries, because I think that Big Tech companies minimizing their tax burden this way is not sustainable for our economies.

Moving onto domestic Polish politics and its relation to the EU in general—Law and Justice, the ruling party, your party, came into power six years ago with the strongest mandate to govern Poland since modern elections started in 1989. Part of this mandate stemmed from a populist distrust of the Polish political establishment that was too often proven to be engaged in fairly deep corruption. Where's the sentiment now, in your view, from the Polish man-on-the-ground on your government and on the ruling party—and also, the relations with the EU, which have oftentimes been fraught since Law and Justice took control of the parliament, the presidency and the government?

We are able to slowly regain public support in the post-COVID circumstances, on the one hand. On the other hand, we have much more quickly than I expected repaired some deficiencies of the first 25 years of post-communist transformation since 1989, and now there are different aspirations in the Polish society. And we have immersed ourselves into those aspirations very deeply—to recognize them, to understand them—and we have done this work for the last nine months. And after nine months, as is the cycle of people being born, our new strategy was one of rebirth. This strategy was presented recently, and it's called the Polish Deal.

This harkens back to the New Deal of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, so as such we call it the Polish Deal. In it we lower taxes for the middle class and for lower-earning people, in particular. We have presented a huge program of investment, a sort of "around the corner" (where people live) type of investment. Not just big investments in scale, but also volume—a number of investments that improve not only standard of living, but also create a platform for productivity growth in particular areas, through education, through broadband connectivity, through promoting exports and promoting small companies to become mid-sized and so on and so forth. So it's a well thought through, interconnected program that we presented just a few short weeks ago.

And so far, so good. It has been well received by the Polish society at-large, by Poles on the ground. I hope that we will be able to again present our very interesting program, which is not so much to fight corruption or the oligarchic system or the lack of some social instruments, because these have been at least to a great degree addressed so far. But we are concentrating now on the third decade of the 21st century, and to catch up with Western Europe in terms of standards of living—and also leapfrogging them, in many instances. My aspiration is to do this, in particular, in the area of the newest technology where the race is kind of on a more equal footing vis-à-vis the older and more mature industries.

It seems to be a part of the Law and Justice mandate to deal with the subject of decommunization, which was an issue during the campaign season, especially with respect to the judiciary. Perhaps some or even most of the country felt that Poland had not adequately addressed this relative to fellow former Iron Curtain Soviet satellites. So how does the decommunization of legacy officials that predate the transformation stand today? Has there been progress on that front?

Not to such an extent as I wished it to happen, but we have done several moves of consequence. For instance, we have acknowledged the role of Solidarity members through financial allowances, and conversely we have deprived the secret communist officers of their very high pensions. Now they have average levels of pension. So those moves, which were critically important for us in bringing back some justice to the society, have already happened.

The judiciary system was not reformed to such a degree as I would have wished before. I expected much more. There's a resistance there supported by misunderstanding of our true intentions from Brussels, which has created an inadequate environment for this necessary judiciary reform to happen in full. So we have made some changes, like random allocation of cases in the courts, which is critically important for the courts to be more independent and objective. We have done this, and the accusations of this being an attack on the judiciary is only in reality a defense of the previous status quo and a defense of these previous incarnations of the judiciary, which most believe requires reform.

Just a couple of final questions on foreign policy and foreign relations, then. Focusing on the Middle East, the current Polish government has stood with Israel many times since Law and Justice took over, including most recently a show of support during the most recent flare-up with Hamas. So how is that relationship currently between the Polish government and the Israeli government, especially obviously given the tense and fraught history with Poland's historical and modern Jewish population?

In 2018, I signed a declaration on behalf of the Polish government with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who signed on behalf of the Israeli government. This was a milestone toward normalizing our relationship, because it acknowledged the complicated past to such a degree and to such an extent as it had never happened before. But since then, there's been election after election in Israel, which never helps in normalizing relationships, I can tell you. Because it's very difficult for those politicians, I understand them, having to be in permanent election mode, to say something positive and constructive toward us given the history, and with the electoral base it's not so easy and sometimes the opposite happens in campaign mode—some politicians want to provoke us, as that plays during campaign season.

So the situation for the Polish-Israeli relationship is in constant flux, and right now is far from being normalized unfortunately. I just hope that these current elections [in Israel] will be the last ones so that we can find some stability in relations, and so that we can bring our economic and otherwise-shared interests to cooperation on a higher level than ever before for the good of our two economies and our two nations.

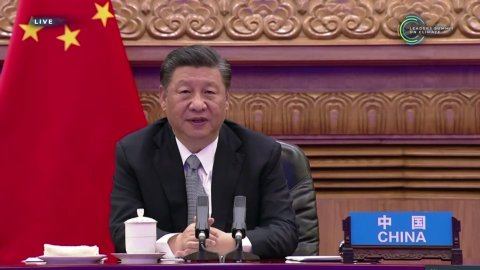

One final question on the geopolitical elephant in the room of all rooms, which of course is China, and the threat posed by the Chinese Communist Party.

It's true.

This is perhaps the most pressing issue of our time. COVID-19 was obviously a gut punch to the entire world, especially the developed world. The Wuhan lab leak theory, after being dismissed by the American media for a year, is now being discussed widely in the U.S. as a viable theory again. And it's becoming increasingly clear that China had no accidental role in either the development of this global calamity—or, at a minimum, they made what was already a bad situation much, much worse via dishonest disclosure and information-sharing with the West.

So in the aftermath of all this, and we're obviously not out of the pandemic in full yet, how is your government examining or reexamining Polish—and more generally, Central and Eastern European—relations with China? There is clearly deep Chinese economic integration and investment in this region as well, given the Belt and Road Initiative and the New Silk Road they are developing, bringing massive capital inflows to the region. And then of course there is Huawei trying to get a foothold in the region, as well. What is the revised viewpoint in this part of the world, and of the Polish government, vis-à-vis China, given all that has transpired?

Well first, I couldn't agree more with President Biden in his attempts to clarify what has really happened. So it's very good that he reverted back to this question, because such a tragic catastrophe as COVID-19 and what it has brought about for the world this past year requires a thorough investigation—a thorough and objective investigation by an international team. And of course, we have to start with Wuhan and what happened there. If China wants to become credible in that regard, they should let this international and objective team in and give them the proper scope for the work that must be done. It is quite obvious to me that this should happen, and I'm pleased with the recent developments in Brussels and in Washington. We have discussed this in Brussels, and on the European Council as well, how to explain all this, what has happened.

On the other hand, we do not want to be less pragmatic than the United States, or Germany or France, with regard to China. And we are going to be very cohesive in a sort of solidarity type of approach with regard to Huawei and some of the other threats emanating from China. But these moves should be made and agreed upon collectively, or at least by the dominant countries. The biggest countries like the United States and the 10 biggest countries of Europe should agree upon a collective strategy vis-à-vis China. But I'm very much a market-oriented and pro-free market politician. So I believe that competition is good and some competition coming from China—not the sort that is subsidized or where there is price dumping or industrial output via slave labor, but outside those abuses, competition is not bad for us. And we are open for the Chinese investments strengthening our intelligence competitive capacities and our abilities to defend vis-à-vis their attacks. I want to be general in this, because we arrested two Chinese spies one or two years ago. So the relationship has been a little bit tense.

But China is such a big, big elephant in the room, as you said, so we have to work together here, the U.S. and the EU, both in terms of trade and investment agreements on the one hand, and then on the other, with regard to the currency manipulation which is happening in China every now and then, and making sure to maintain cohesion with the NATO alliance, which has to strengthen and which has to spend more money on defense and military equipment and work together on these huge challenges such as China.