Proximity flying – like many of life's other challenging distractions, such as rodeo, fire-eating and crack cocaine – is never going to be for everybody. Neither, as I suggest to elite wingsuit flier Ellen Brennan, is it the kind of recreation that anyone is likely to embrace on impulse, in some fleeting moment of bravado.

"This," she replies, "is not something you can dabble in. This is not simply a sport. This is a different way of living your life."

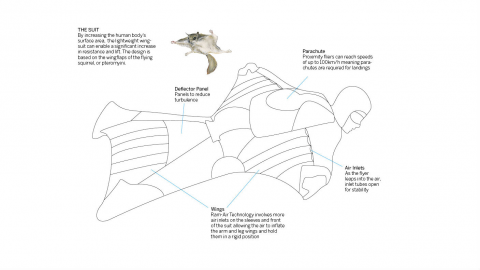

We're standing at 3,840 metres, just below the summit of Mont Blanc, a position we have reached by cable car from the town of Chamonix. Today the peaks are wreathed in cloud and the light snowfall is ruffled by southerly winds; conditions that mean that the 26-year-old American is unable to opt, as she often does, for taking the quick way down. She points out the nearby ledge, or "exit point", from which she normally jumps, in a suit cut from light paragliding material that gives the wearer the appearance of a flying squirrel.

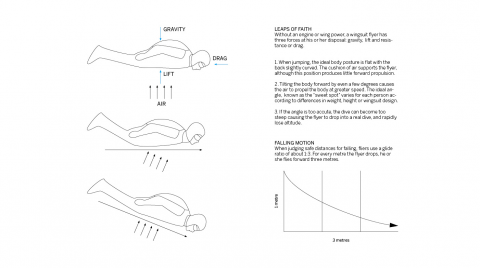

"For the first two seconds," she says, "there is this perfect quiet. That feeling is wonderful. Then you hear the rush of air. You fall for about 80 metres before the suit inflates and starts flying. The more speed you have, the further you're able to glide." When leaving a cliff, she says, attention to wind and other climatic factors, some imperceptible to a novice, is vital. "People who don't pay attention to these things tend to get hurt," she says. "And most of them die."

Brennan is one of the world's leading practitioners of a discipline that, in its current form, began less than 20 years ago. The design of the custom-made wingsuits, which typically cost around £1,500, has evolved to the point that experts can now fly between trees or rocks with a clearance of no more than a couple of metres on either side, at a typical speed of 193 km/h, before deploying a parachute to make a safe descent. Make a mistake, she concedes, and "the chances are that the emergency room is not going to be able to help you".

There is a famous saying in the world of freefall parachuting that "altitude is safety". Even so, I tell Brennan, just the idea of having to clamber across to her exit ledge is making me feel queasy.

"Most of the crucial demands of wingsuit flying are mental," she says. "The skill set is one that anybody can learn. But you have to be calm when you jump. If you're stressed, a jump is not going to go well."

Proximity flying developed from base jumping: the art of freefall parachuting in dangerous proximity to cliffs, buildings, or other elevated sites. Other mountain ranges, notably in Utah (where Brennan grew up), Colorado and Norway are popular with wingsuit fliers, but no region attracts the elite practitioners more than this area of the Alps. Here, the terrain allows them to leap from altitude, then fly very low over elevated plateaux before emerging over much lower ground, at which point (after a flight time of around three minutes) it becomes possible to land safely with a parachute. Ellen Brennan moved here in 2012 with her boyfriend, Laurent Frat, another star proximity flier, so as to become intimately familiar with this unforgiving terrain.

The practice of wearing helmets equipped with cameras, then posting the resulting footage on YouTube, has encouraged some fliers to take ever more alarming risks. They have filmed themselves negotiating narrow ravines and rocketing through gaps in stone outcrops with an apparent recklessness that suggests their worst fear would be the words "Game Over" appearing on the skyline.

One of the most popular internet clips, with over 3.5 million views, shows Brennan's fellow American Jeb Corliss flying below the 1053 foot Royal George Bridge in Canon, Colorado just as his best friend, an Australian named Dwain Weston, was attempting a synchronised flight above it. Weston hit the bridge, severing his torso. Corliss landed soaked in his friend's blood, having been obliged to take evasive action because of what he described as "stuff" in the air. The first thing he saw on landing was the Australian's severed leg. What remained of Weston's lifeless body drifted gently down to earth; the collision had caused his parachute to deploy.

The question of whether such footage should be posted on the internet is debated with some warmth in the wingsuit community. What is indisputable is that these deaths are not of the kind that can be sanitised with phrases such as the American euphemism, "to pass".

Corliss, not a man plagued by self doubt, became internationally famous after making illegal base jumps from buildings including the Eiffel Tower, and is a showman of the old school. Brennan, who is 5ft 2in (157cm), softly spoken and a qualified nurse – a job she does in order to fund her main passion – seems a less likely recruit to so hazardous a pastime. Even though upper body strength is an advantage in wingsuit flying, she was one of 16 elite fliers recently invited to an international competition in China, and regularly finishes in the top four in such mixed contests.

Fatality rates in the sport may not have reached those endured by some First World War allied aircraft squadrons, where death was so common as to inspire jokes such as "Don't start any long books," and "Don't buy any green bananas," but a 2012 study by Dr Omer Mei-Dan, wingsuit enthusiast and assistant professor of orthopaedics at the University of Colorado, indicated that 72% of fliers had witnessed death or serious injury, and 76% had experienced what they categorised as a "near miss". Known fatalities are running at about two dozen a year, a number that has been steadily increasing as more skydivers (newcomers are required to have made a minimum of 200 freefall jumps) are attracted to the sport. Mark Sutton, the ex-army officer who parachuted into the opening ceremony of the London Olympics dressed as James Bond, died in a wingsuit accident close to Chamonix in August last year, aged 42. In the summer of 2012, death rates were such that the town introduced a ban on all wingsuit flying, an unpopular measure which was withdrawn after a couple of months. The average active career of a proximity flier has been estimated at six years, after which it is generally curtailed by death, injury, or prudence.

Brennan doesn't need statisticians to remind her of the dangers of wingsuiting. Just a couple of months ago, three friends, including her close collaborator, French cameraman Ludovic Woerth, died after jumping from a helicopter in the Lütschental valley, just across the border from here, in Switzerland.

Brennan won't comment on the causes of the crash, in which Woerth and New Zealander Dan Vicary died instantly. The third flier, American Brian Drake, survived for more than a week in a coma. The highly-respected Croatian wingsuit designer Robert Pecnik says that the incident appears to have been the result of human error: the victims were either too low when they jumped, or had chosen the wrong line of flight across the valley, so that they found themselves with insufficient elevation and, having no option but to fly on, ploughed into the ground.

The entire flight was captured on cameras worn by the dead men, though the images have not been made public. Brennan, who has seen the footage, says that she hopes that, once it has been fully scrutinised in order to reveal the reasons for the accident, all film will be destroyed for the relatives' sake.

THERE WILL BE BLOOD

Limited though the impact of proximity flying may have been on mainstream culture – many people I spoke to had never even heard of the sport – it would be hard to overstate its significance in the context of the long and troubled history of man's attempts at unpowered flight. David Darling's entertaining study The Rocket Man, published in 2012, examines the history of eccentrics like the American Clem Sohn, who was jumping out of planes at 18,000 feet with homemade canvas wings as early as the 1930s. A crowd of 200,000 saw Sohn die at the Paris Air Show in April 1937, after his parachute malfunctioned. He was 26.

The modern wingsuit was developed largely through the efforts of two Frenchmen: Loic Jean-Albert, and Patrick de Gayardon, who met when each was a member of the French skydiving team, based in Gap, in south-eastern France. The latter, who once predicted that arthritis would end his career, died in 1998 in Hawaii, while testing what he had assumed would be an improvement to his parachute. Jean-Albert, widely regarded as the father of proximity flying, retired from participation after breaking his back in two places in 2007. "You have a lot of friends who die," says Jean-Albert, who recently moved to the island of Réunion. "Skill does help, but skill can never eliminate risk".

"Loic Jean-Albert made the first wingsuit that was available to the public," says Brennan. (Jean-Albert unveiled his "CrossBow" suit in 1998). "That was huge because, before that, everybody was literally dying, trying to do it."

A recurring figure in both Rocket Man and Matt Sheridan's seminal 2012 documentary on the history of wingsuiting, Birdmen, is Corliss. Apart from his nightmarish flight below the bridge in Colorado, the 38-year-old has had several other unenviable experiences of his own, notably when he slammed into the rock face behind Howick Falls in South Africa in 1999, an accident he barely survived. Two years ago he was seriously injured while proximity flying off Table Mountain in South Africa.

I spoke to Corliss at his home in Marina del Rey, Los Angeles, where he was about to undergo surgery on his anterior cruciate ligament, an operation that will require six months of rehabilitation. "How many friends," I ask him, "have you lost?"

"A lot," he says. "I'm not sure about the number. Of my close friends, I would say 50%."

Corliss is regarded as something of a loose cannon by some in the wider wingsuit community: unfairly, says Brennan, because "he is extremely highly skilled and, behind it all, he is a very smart guy". Brennan got into free-fall parachuting at 18 with the encouragement of her father, Frank, also an enthusiast. Corliss, who was born in New Mexico but travelled widely as a child, has been diagnosed by one psychiatrist as suffering from counterphobia, defined as a pathological desire to confront one's fear. Talking to proximity fliers, it is difficult to identify a single personality type, though most assert that the extreme demands of the sport help to put the stress of everyday life into some perspective.

If Brennan and Corliss have anything in common, it's that, when filmed at altitude, each has the unflinching expression that former Manchester United manager Alex Ferguson once described as "the glazed eye": a characteristic that, the Scotsman believed, was an indication of a sportsman's capacity for courage under duress. Courting popularity has never been a priority for Corliss. "Listen," he tells me, "I talk about the deaths. I talk about the disasters."

"And if you die?"

"If I die, I want that footage on TV the next day."

"Why?"

"Why? Because this is not chess. This is not backgammon. This is not . . . " (Corliss racks his brain for a yet-more-contemptible pastime, and finds one) "golf. This is dangerous. I believe that footage of fatalities is way more important than film of some guy flying across a beautiful meadow. What we are doing here is very important. I believe that flying is what evolution is about. Think of the squirrels."

"OK."

"At the beginning, there were probably only a very few squirrels that even contemplated flying from tree to tree. The other squirrels thought they were crazy. I imagine hundreds of them died in the attempt. But then, in the end, one of them managed it. Now that, to me, is evolution. And now we are evolving, through technology and through skill. I liken what we're doing in proximity flying to the first animals that left the water. We are evolving and growing. And becoming stronger. What else," he asks, "is the purpose of life?"

I mention the Norwegian base jumper Karina Hollekim, a friend of his, who, after suffering serious spinal injuries in 2006, became the subject of a documentary called Twenty Seconds of Joy, released the following year. "At one point in that film," I remind him, "she says that she has decided to stop jumping and devote her time to 'something less selfish'."

"Well," Corliss replies, "that all depends how you define 'selfish'. I think that there's nothing selfish about following your dream. Karina was trying to turn her dreams into reality. That isn't selfish. A lot of people don't seem to grasp quite what it means to be able to fly. This is something we have all dreamed about – all of us – for centuries. Would you ask a bird, 'When are you going to give this up?' Any human being that has ever flown [in a wingsuit] and who knows that feeling, I don't believe that they are going to give it up."

Corliss once posted on Facebook that "My death shall be violent, brutal, and there will be blood," which would indicate to me, I tell him, that he probably doesn't expect it to happen in bed.

"Do you want to die in bed?" Corliss replies. "Is that really what you want? If it is, you can't have spent much time around old folks' homes. I watched my grandmother die from cancer – in bed – and it was horrific. I can't imagine anything worse. What is important is how you live. Death is inevitable. I don't care how or where I die. Those details are not relevant. And who knows, death might just be one of the most beautiful things that we get to experience."

THE GREATEST REWARD

While Corliss's claims of kinship with maverick rodents might strain the credulity of some readers, it is undeniable that advancements in wingsuit design mean that the sport's limitations are receding rapidly. Suits have developed to the point where the best proximity fliers can manoeuvre in a way that mimics the instincts of birds: sensing and exploiting thermal currents and, in the right conditions, rising in the air.

The next obvious goal for wingsuit enthusiasts is the ability to land without the benefit of a parachute. A few, including Corliss, have achieved this accidentally, but always at the cost of spending several months in plaster. A viral video on YouTube purports to show a young man landing on a lake in Northern Italy, but this footage was simulated.

In May 2012, a British stuntman named Gary Connery jumped in a wingsuit from a helicopter at 732 metres above Oxfordshire and landed unscathed, using no parachute, on a pile of cardboard boxes 106 metres by 14 metres wide. Robert Pecnik asserts that, in a hundred years' time, the safety and popularity of wingsuiting will be such that news of fatalities will raise no more public interest than a death in a motorcycle race.

On my last day in Chamonix, I meet Brennan in a café at the foot of Mont Blanc. Isa, her Australian shepherd puppy is lying at her feet. "Did I dream it," I ask her, "or did a dog lover once say that gravity was man's second best friend?"

"Well, I definitely like gravity," she says. "These things are hard to explain to people who have never done what we do. I love the feeling of a long hike up the mountain, against gravity, before a jump. That could take five hours or more. I like that feeling of pushing my physical limits, on the ascent. Because when you finally do jump, and you're flying at the very limit of your capabilities, that's when you get the greatest reward."

"Is it addictive?"

"Very. When you land, you have all these endorphins coursing through your body. The greater the risks you've taken, the more you feel that. And you establish close connections very quickly with people in the wingsuit community," she says. "I've tried dating people who don't jump. It never works."

The proximity flying community, as with most families, is never closer than when it loses a member. How did she cope in the aftermath of the deaths of her three associates, of whom one, Ludovic Woerth, was a particularly close friend? Accompanied by other proximity fliers, including her boyfriend Laurent, she "went to the site [of the accident] to try to understand exactly what happened. We found the impact points in the ground." The film from the dead men's helmet cameras, she adds, was "very hard to watch. Those images are no longer the first things I see when I wake up in the morning. When you have a friend die," she says, "and you next go out and make a jump, once you are ready, it is huge. It helps clear your mind. You just go out there. You just go out there and fall."

At Woerth's funeral, the wingsuit community gathered to make what they call an ash jump. "There were 22 jumpers," Brennan remembers. "And they scattered his ashes over the valley. I waited at the bottom. I still wasn't ready to fly again. It was very moving. And that is what we do," she adds, "when people die."

Proximity fliers, in common with goalkeepers, infantrymen, and others whose lives involve the anticipation of possible catastrophe, tend to be superstitious. There was a fourth flier who had intended to jump with Ludovic Woerth and his two friends. Dressed in his wingsuit, ready to board the helicopter, he pulled out because he "just wasn't feeling it". Before Dwain Weston (a veteran with a reputation for absolute fearlessness) made his fatal jump, Jeb Corliss had noticed how, in the plane, "he seemed a little bit scared. He grabbed my hand and said, 'Just remember, whatever happens, happens'. We had done a lot of hardcore jumps together. He had never said anything like that to me before."

Brennan tells me how she used to carry a lucky penny when she jumped. "I stopped doing that," she says, "because I started to wonder how I would react if I ever lost it."

"We've talked about other people getting into difficulties. Have you ever felt: hang on. I'm in serious trouble here?" I ask her.

"Once, in 2009, which was my first season. I was here in France. It had been a two and half hour hike to the exit point. It was in the evening. I had no headlamp with me. It was windy. At that spot, you had to jump with your left foot. I push off with my right. So already I'm not happy. I'm tired. I'm pushing off with the wrong foot. It was an early wingsuit. With those, if you lost your speed, which I did, you never got it back. I passed over this huge forest and I realised I had to pull [the parachute cord]. Then I felt myself being drawn back," she says. "Not towards the landing area but towards these tall, tall trees. And I ended up landing on top of them. They tell you to spread your parachute, which I tried to do, but I just kept falling. When I stopped and looked down I was literally a foot off the ground. That is the most dangerous situation I have ever been in. It could have been much worse. I didn't break any bones. The important thing," she says, "is to learn from it".

"Learn from it? As opposed to what?"

"As opposed to concluding that you are invincible."

"Do people do that?"

"Some do," Brennan replies, adding, with a mischievous look, "Russians, usually".

On my way to meet her, I mention, I passed a woman of about her age driving a people carrier decorated with a sticker that read, Baby on Board.

"Is there anything that would stop you from flying? Children?"

"I don't think that I could stop doing what makes me happy. Not entirely. If I had children I probably would not proximity fly. I would do nice scenic flights. But quit altogether? I honestly don't think I could. Even now, if I don't jump for a few weeks, I become . . . a person that I don't like."

"Is there anybody telling you to stop right now?"

"My mom. She hates it. But then don't you think this all comes down to the question of what you want from your life?"

And then, just for a moment, Brennan starts to sound a little bit like Corliss: "Do you want to go to school, leave, find a husband, buy a house that is way too big, buy too many cars that are way too big, make babies, live in debt, work your ass off, never get out of that hole and exist knowing that this is all that you'll ever have, apart from maybe two weeks vacation in Florida every summer? Because that's not what I want. I want to see the world. I want to do things that people tell me I can't do. And that domestic grind, to me, is not life. And personally . . . " Brennan pauses, as if searching for a way to justify her perilous vocation in a single phrase, "I want to live."