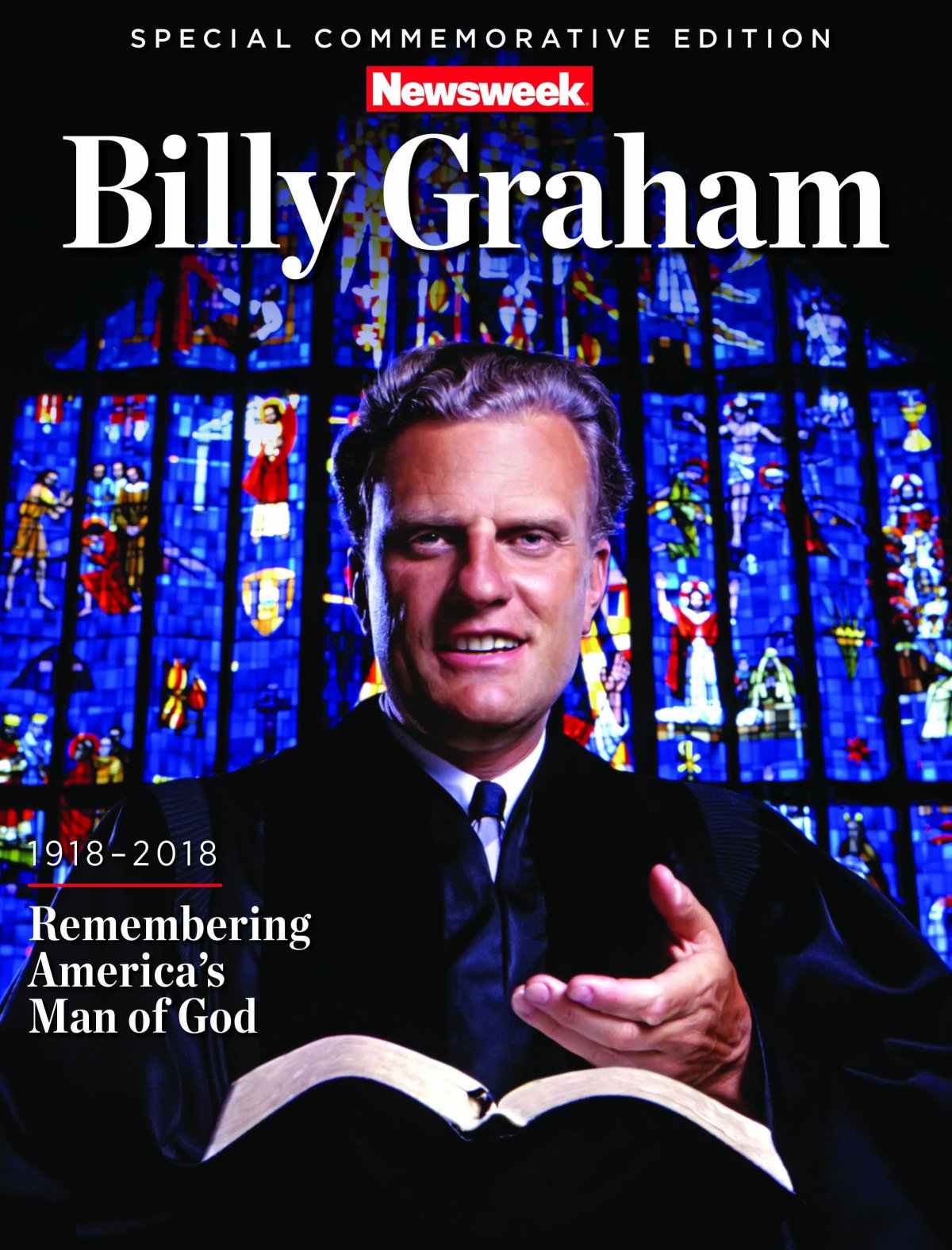

This article, along with others celebrating the life of America's favorite preacher, is featured in Newsweek's Special Commemorative Edition: Billy Graham

At first blush, it would seem hubristic to write yet another biography of Billy Graham, especially one that focuses on his relationships with American presidents. At 88, Graham is, and has been for more than five decades, one of the most celebrated men in history, the subject of dozens of biographies and one excellent autobiography. And the evangelist's own transparent nature and predilection for truth telling make a portraitist's job both too easy and too hard: He is exactly what he seems to be. For all these reasons, you might imagine there's nothing new to say about him.

How wonderful, then, that the authors of The Preacher and the Presidents: Billy Graham in the White House approach their task with such passionate inventiveness. Nancy Gibbs and Michael Duffy, both veterans at TIME magazine, have that peculiar gift among newsmagazine writers for being able to shape masses of complex and contradictory information into a compelling narrative. Even better, they have sifted through all the source material—including never-beforepublished memos by TIME correspondents—and packed their story full of details so delicious that even if you've read them before you're happy to read them again. They also had access to Graham himself, and though their interviews are not revelatory, they do show a lion in his winter, turning over the events of his extraordinary life sweetly, with pride, puzzlement and remorse.

The Preacher and the Presidents gives you Lyndon Johnson lying in bed, watching three television sets and refusing to sleep until he finishes all the newspapers stacked on his nightstand. When Graham enters the room, the president kneels in his pajamas. You see Nixon, joining Graham at a 1970 Crusade and then, when the offering plate comes by, realizing he has no cash. In one of the book's most poignant passages, you see Reagan, post-presidency and already in the advanced stages of Alzheimer's disease, telling the visiting evangelist that before they can pray, they have to wait for the arrival of Billy Graham.

It is easy to be sentimental about Graham, but Gibbs and Du y are clear-eyed about his faults: a consuming passion for politics and a love for power that could undermine his neutrality and his authority as a Gospel preacher. They show him advising, kibitzing and fl attering presidents and would-be presidents. He boasted during the 1952 election that he could swing 16 million votes, and throughout his life begged politicians to invoke God more frequently in their speeches. It is in part thanks to Graham that Eisenhower inserted "under God" into the Pledge of Allegiance and stamped "In God we trust" on our bills. Jerry Falwell has been credited (or blamed, depending on your point of view) for bringing religion into the political sphere, but Graham was there long before him.

The heart of the story is the inexplicable friendship with Nixon, an episode that shows Graham at his worst and at his best. With Eisenhower and Johnson, Graham was the righteous soldier of the Lord, using his access to the Oval Office to fight relentlessly for an American spiritual revival. But in his enthusiasm, Graham, whose best quality is the ability to see the best in others, imagined a goodness and conscience in Nixon that, finally, wasn't there. Graham fought harder for Nixon than for anyone else—and more publicly. To some extent, Graham was complicit in Nixon's disgrace, and the evangelist's reflections on his own shameful participation in Nixon's paranoid anti-Semitic imaginings (Graham's contributions were captured on tape and made public 30 years later) sound like the bewildered reminiscences of a spurned lover. "I don't understand it," he told Gibbs and Duffy earlier this year. "I can't even remember it. I never felt that way. I never thought that way, and I was just trying to agree with what he said or something." In 1973, as Watergate threatened to bring the president down, Nixon returned few of Graham's calls. The next year, after Graham read the transcripts of the White House tapes, he became sick.

After Nixon, Graham befriended and even loved presidents and their families—the Reagans, the Bushes, the Clintons—but he never again flew so close to the flame. At the end of his life, Graham, who is not given to introspection but has clear hindsight, tells Gibbs and Duffy that he had been blessed with a character devoid of jealousy or hate. "That was a gift from the Lord," he told them. "Jesus…loved sinners, people who didn't deserve it, that's what grace is. It means God gives us forgiveness that we don't deserve. And to me that's a wonderful thing." Admirers frequently called on Graham to run for president, but no president ever loved his people as deeply as this pastor did.

From the Newsweek Archive, 8/27/2007, By Lisa Miller

This article, from the Newsweek archives, was excerpted from Newsweek's Special Commemorative Edition: Billy Graham. For more on the legacy of America's man of God, pick up a copy today.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.