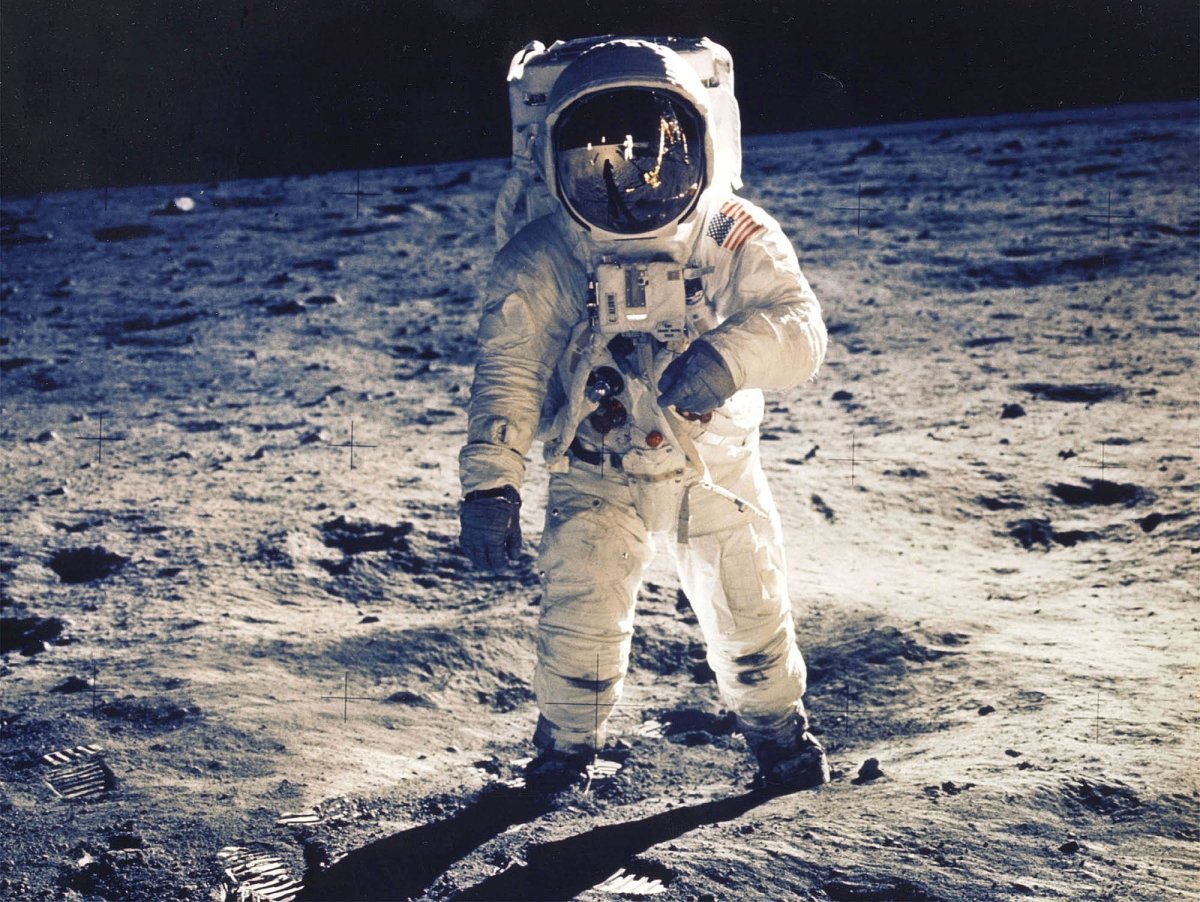

When NASA was preparing to land humans on the moon for the first time in the 1960s, the agency expected plenty of challenges. A surprising one was the pervasiveness of moon dust, which quickly proved capable of getting everywhere, interfering with the airtightness of sample boxes and damaging spacesuits.

Now that the agency has its sights set on returning to the moon in the next decade, scientists want to better understand the havoc lunar dust wreaks. A new paper published in the journal GeoHealth last month tackles that by creating mock moon dustand exposing human and mouse cells to it. The results are worrying: The imitation dust killed cells and damaged the DNA they contained.

Of course, that's not the same as real humans or animals exposed to real moon dust, so it may not be an entirely accurate reflection of the risks of lunar landings. To try to cover their bases, the researchers used five different recipes for fake moon dust. Until we return to the moon, it's the best scientists can do to evaluate the risks of moon dust.

Related: NASA cancels Rover meant to mine water from the moon

Dust is a bit of a misnomer. The terrestrial stuff is made of dirt, skin cells and particles shed by furniture and the like. Moon dust is essentially tiny particles of glassy rock formed when things crash into the lunar surface and briefly melt the rocky crust.

That makes for much more threatening dust bunnies, hence all the problems the first moon visitors experienced. (One astronaut called his seeming allergic reaction to the dust "lunar hay fever.")

Previous studies have exposed rats to imitation moon dust or tried to extrapolate lunar conditions from studies of people living near certain types of volcanic eruptions, since volcanic ash is also essentially pulverized and melted rock.

The new study took a different approach, exposing cells to moon dust and seeing how long they survived, then studying the DNA they contained. There were variations in cell death rates, depending on the precise imitation moon dust used and the concentration cells were exposed to—but in general, the majority of cells died. Nuclear DNA, which encodes instructions for most of a cell's functions, also fared poorly.

The team wrote that they hope to get their hands on actual moon rock samples in order to see how closely their results match.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Meghan Bartels is a science journalist based in New York City who covers the science happening on the surface of ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.