In 2008, Mike Campbell was abducted by militiamen in Zimbabwe along with his wife and son-in-law. Savagely beaten by their captors—believed to be loyal to Zimbabwe's then-President Robert Mugabe—the family were dumped by the edge of the road.

Campbell's crime, as his captors saw it, was being a white man that owned land in Zimbabwe. Eight years earlier, Mugabe had instituted controversial reforms that empowered black Zimbabweans—often Mugabe's cronies or members of the ruling ZANU-PF— to forcibly repossess white-owned land.

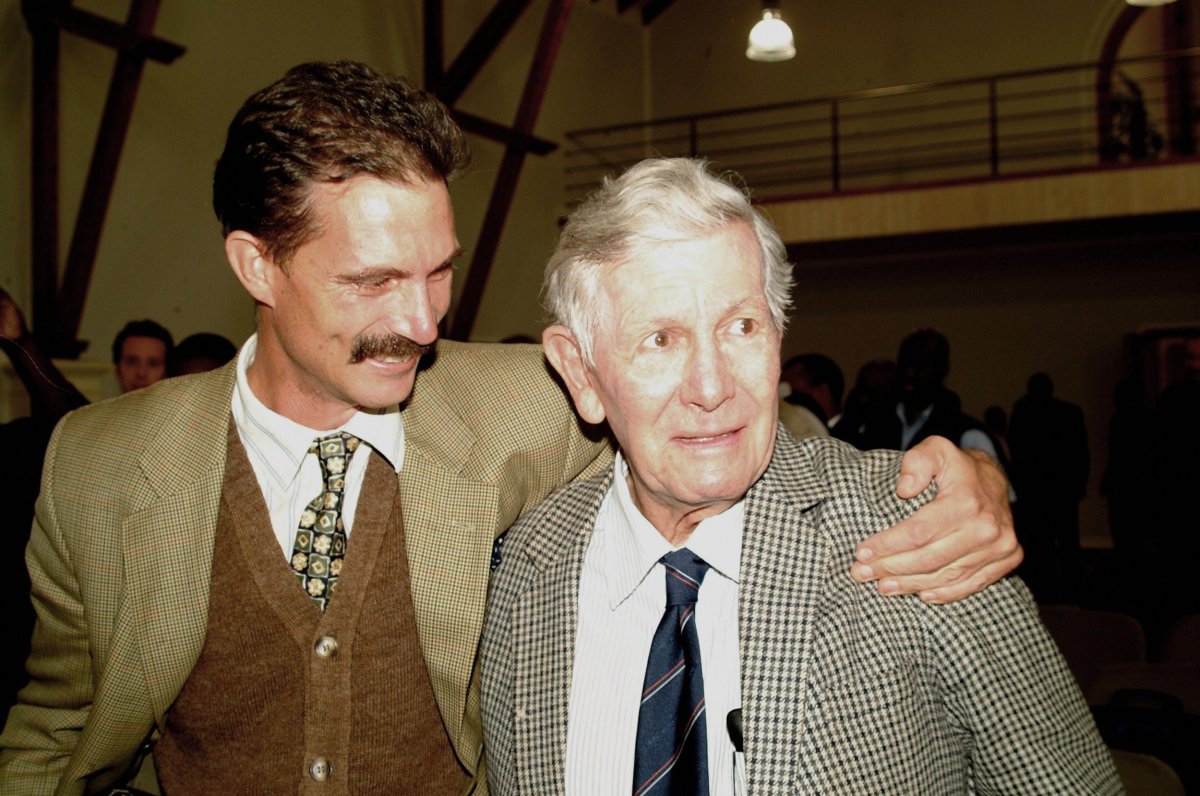

Campbell had opposed the reforms and took Mugabe to court, eventually resulting in a November 2008 ruling by a regional tribunal that ordered the Zimbabwe government to protect farmers' rights. The ruling was ignored by Mugabe and three years later, in 2011, Campbell died as a result of the injuries he suffered.

A further six years later and it is Mugabe that has now gone, resigning on Tuesday less than week after the Zimbabwe military seized control of the state broadcaster and placed him and his family under house arrest.

But Campbell's son-in-law, Ben Freeth, 48, says he doesn't hold out much hope that Mugabe's successor— former vice-president Emmerson Mnangagwa, who was inaugurated on Friday—will do much more for the country's embattled and exiled white farmers.

"No, I don't think I would have any confidence in Mnangagwa, because Mnangagwa has been part of it all the way through," says Freeth, speaking to Newsweek from Harare on November 15, before Mugabe's resignation and Mnangagwa's inauguration.

"But I don't believe that Mnangagwa would be able to hold things together in quite the same way as Mugabe has, certainly on the international front and also on the local front."

In his inauguration speech on Friday, Mnangagwa said that while land reform could not be reversed, his government would seek to compensate white farmers.

Read more: Is the Crocodile a fresh start for Zimbabwe, or a new Robert Mugabe?

When Mugabe's land reform policies came into force, there were around 4,00 white-owned farms in the country. After years of land seizures, there are now less than 100 remaining. In some cases, white farmers have been killed and their homes torched.

Mugabe remained unrepentant about land reform, saying as recently as August that he would not prosecute those responsible for killing white farmers during land seizures.

The policy has been a disaster for Zimbabwe's economy. International bodies and Western countries slapped crippling sanctions on Mugabe's regime after the reforms, and while the seizures may have benefited some black families, many of those who took the farms were incapable of running them. As crops rotted in the fields, Zimbabwe's economy collapsed in the late 2000s after one of the worst periods of hyperinflation ever seen.

In 2017, the country remains in economic crisis, with high unemployment and dwindling foreign exchange reserves that have led to the central bank printing a pseudo-currency known as "bond notes", which have no value outside the country.

"We've had 37 years of a country that was the second most developed in Africa descend into becoming one of the smallest economies in Africa, where a quarter of the population has fled, where tens of thousands of people have been killed, where hundreds of thousands of people have left their homes...there's no one going to be unhappy about the end of an era that's brought so much suffering and destruction, but it's just what takes its place that worries us," says Freeth.

Freeth now heads up the Mike Campbell Foundation, which works to obtain justice for people who have been beaten, wrongly detained or had their land taken by Mugabe's government. In August, Freeth was part of a group that served formal notice to Mugabe, three ministers and the Zimbabwe government collectively for international legal proceedings under the auspices of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) to obtain compensation for dispossessed farmers.

And Freeth says that he is confident that his family and others affected by the farm invasions will eventually get justice, even if it comes from outside Zimbabwe.

"The wheels of justice often take a very, very long time to turn, but I think that if you are in the right—which we are—if you continue to document and pursue justice, eventually those wheels do turn," he says.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Conor is a staff writer for Newsweek covering Africa, with a focus on Nigeria, security and conflict.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.