Poring through the post-mortem of the man federal prosecutors have called the most egregious fraudster in the history of the United States, it's hard not to be shaken by the crimes of Dr. Farid Fata, the former hematologist and oncologist whose licenses have now been revoked.

Once one of Michigan's most respected doctors, with a sprawling practice across seven cities that had served over 16,000 patients since 2005, Fata was sentenced July 10 to 45 years in prison. Last September, he pleaded guilty or no contest to 23 counts of health care fraud, two counts of money laundering and one count of conspiracy to pay and receive kickbacks—but even all that fails to capture the depths of his evildoing.

In anticipation of Fata's sentencing hearing that began on July 6, the government released a 100-plus-page memorandum to the public in May, detailing what it discovered about his scheme to defraud Medicare and other insurers by exploiting patients. Federal prosecutors allege Fata intentionally prescribed over 9,000 unnecessary injections and infusions to at least 553 patients over a six-year span. These treatments amounted to nearly $35 million in insurance billings.

Fata lied to patients about their cancer prognoses by claiming they required chemotherapy when they simply needed observation; he hoodwinked others into the infusion chair by telling them that they had to receive "maintenance" chemo to stave off cancers already in remission; and perhaps most ghastly, he implored those he knew to be terminally ill to remain under his care as he pumped poison into their soon-to-be lifeless bodies.

But it would be a mistake to look at Fata and see only a heartless and greedy monster. His actions, appalling as they were, were not performed in isolation; they are emblematic of systemic issues that have plagued the medical community since long before he ever completed his prestigious residency at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in 1999.

"It's one of the most extensive cases of fraud I've heard of," says Nicholas G. Evans, a medical ethicist at the University of Pennsylvania. "But it involves common problems known about in the field of medical ethics."

To step into an oncologist's office is to put your life in someone's hands. "Patients develop an almost religious connection to these doctors," says Jeffrey Stewart, an attorney who is representing two former clients of Fata's.

According to the testimony provided by Fata's victims, the doctor repeatedly took advantage of this connection, as well as fear, to obscure the uselessness of his medical treatments. "He stated that [my mother] had a very aggressive cancer that would become untreatable if she stopped chemo and then he wouldn't be able to save her," wrote Michelle Mannarino, the daughter of a Fata patient, in an impact statement gathered by the prosecutorial team. "Several times, when I had researched and questioned his treatment, he asked if I had fellowshipped at Sloan Kettering like he had."

At seemingly every stage of cancer (including no cancer at all), Fata promised his patients that remission was 70 percent likely, but only if they were completely loyal to him. One terminally ill woman spent the last few moments of her life angry with her family for questioning the wisdom of declaring bankruptcy to continue paying for Fata's care. "She kept putting things off, thinking that she would have time 'when she got better'.... [Our mother] was never able to accept that she was dying because Fata convinced her she was not," the family's impact statement says.

Fata also bamboozled patients into receiving additional doses of the immunosuppressive drug rituximab even after they were successfully treated for their lymphoma—in some instances, for as long as three years. By the time Fata was arrested, their immune systems had been permanently devastated. Others were left with decaying jaws and never-ending bouts of intense pain by the bone cancer–fighting drug Zometa.

He deflected suspicion from the rituximab patients and medical staff by claiming that it was a part of a revolutionary "European" or "French" protocol, even going so far as to forge a medical paper after his arrest that supposedly proved the value of rituximab. Elsewhere, he kept a tight leash on information by denying patients access to their full medical files—preventing them from being able to effectively seek a second opinion.

IT TAKES A WHISTLEBLOWER

Angela Swantek, an oncology nurse with 19 years of experience, told The Detroit News that she went in for what she thought would be a routine job interview with Fata in the early spring of 2010. By the end of it, she left dismayed over the medical care she saw being administered to patients.

For example, Swantek saw people hooked up to infusion chairs being slowly pumped full of drugs that were meant to be given via a quick IV injection, and other treatments like Neulasta, a human growth factor, being administered immediately after chemotherapy, instead of after 24 hours, as recommended. Any trained professional should have instantly seen these procedures were inappropriate and even dangerous, yet when Swantek brought it up, all she got from the nurse on staff was indifference. "That's just the way we do things here," she recalls being told.

Swantek reported her suspicions to Michigan's Bureau of Health Professions that March. More than a year later, in May 2011, she received a letter from the state-run Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs (LARA, which manages the bureau) telling her that an investigation had cleared Fata of any wrongdoing. But, Swantek says, the state never reached out to her.

LARA maintains that it interviewed Swantek and conducted its probe to the best of its ability, but attempts by Swantek and The Detroit News to obtain the file of the investigation were denied, with the state claiming it could not release any information because of privacy laws surrounding the state investigation of a medical professional.

That obliqueness is baked into every layer of self-regulation within the medical field, says Brian McKeen, an attorney who is representing several of Fata's former patients in pending civil court lawsuits filed against him. McKeen cites the practice of medical peer review, which allows professional organizations like the American Medical Association and hospitals to conduct internal reviews of their members and staff without the possibility of scrutiny. In Michigan, even though reports conducted by a review entity, such as the AMA, can be released to the public, they are, by state law, under no circumstances allowed to reveal the identity of anyone involved in the investigation. That information also cannot be disclosed to lawyers like McKeen who seek to demonstrate a pattern of negligence by a specific medical professional.

The policy is ostensibly meant to safeguard those who seek to report doctors from retribution or liability, but it also means that the public has no way of knowing about a physician's past brushes with charges of negligence. None of the patients who entered into Fata's care could ever have been made aware of the 2010 allegations against him or if the state was indeed justified in finding him free of wrongdoing. It also means that any third-party attempts to verify whether an institution actually did its due diligence in investigating a medical professional will be virtually impossible.

Meanwhile, there are scant resources and manpower available to investigate medical negligence, both at the institutional and state government level. "There's really no medical police around to catch corruption," Evans says. "It often takes a whistleblower."

From the time Dr. Soe Maunglay began working for Fata's practice, Michigan Hematology Oncology, in mid-2012, their relationship had been rocky. Soon after he arrived, Maunglay requested that a physician be present anytime one of his patients was undergoing chemotherapy; in response, Fata assigned Maunglay to a location and hours that kept him far away from his own patients. Maunglay's suspicions further developed after he caught Fata lying in 2013 about MHO having already obtained certification from the Quality Oncology Practice Initiative program when it actually hadn't. His growing frustration with Fata led him to tender his resignation for that August.

Around the weekend of July 4, 2013, Maunglay was looking in on patients at the Crittenton Hospital Cancer Center, where Fata operated a private clinic, when he came across Monica Flagg, who had broken her leg. Only a few hours earlier, she had received the first of many planned and costly chemotherapy sessions. Looking at Flagg's medical chart, Maunglay soon realized that Flagg was likely cancer-free, and later that weekend he urged her to get a second opinion.

Horrified by the incident, Maunglay began to look at Fata's other patient files. He got in touch with George Karadsheh, MHO's practice manager, about his concerns. Afterward, Karadsheh formally reached out to the FBI with Maunglay's findings, starting the cascade of events that would end in the FBI raiding Fata's offices and arresting him.

TOO PROFITABLE TO JAIL

Perhaps the biggest reason Fata had gotten away with his crimes for years was the simplest one: He was too profitable to tattle on. According to the federal investigation, by the time Fata was apprehended, his practice purchased $45 million worth of drugs annually for a staff of three doctors. The median amount spent by a full-time oncologist is between $1.5 million and 1.9 million, according to a 2015 report on oncology trends. He branched out with an in-house pharmacy, Vital Pharmacare; a radiation treatment center, Michigan Radiation Institute; a diagnostic testing facility, United Diagnostics; and his very own charity, Swan for Life.

He accomplished this growth largely by treating his patients as if they were actors at a cattle call, lining up 50 to 60 a day to hand off to unlicensed doctors before spending five to 10 minutes at the end of each visit seeing them personally. Then he pushed for longer or unneeded treatments, overdosed patients so he could use up the entire containers of medication he had billed for, harangued the dying (when he couldn't convince them to keep taking treatment) into staying at the hospice he received kickback money from and pressured others to only use the services of businesses he owned. Given the choice between making his patients healthier and making himself wealthier, Fata always chose the latter.

Fata's merciless profiteering was certainly at the extreme end of the spectrum, but Evans says it's a choice many doctors make. "There are contradictory demands on the health care system," he says. Many doctors, even unknowingly, bend their treatment decisions toward making the most money possible. Rarely does this lead to outright fraud, but often it is enough to get in the way of the principal precept of bioethics: first, do no harm.

In one of many examples, Evans cites a 2013 study from The New England Journal of Medicine that found that urologists who owned an intensity-modulated radiation therapy service, a cancer treatment with a high reimbursement rate, were more than twice as likely than urologists who didn't own IMRT service to prescribe it to their patients. "The conclusion here is that ownership of expensive-to-access medical services constitutes an incentive to prescribe those services to patients, regardless of whether those patients would benefit more from that service than some other, cheaper therapy," he says.

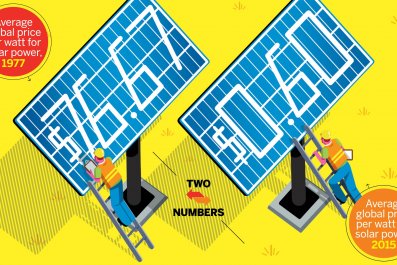

The expansion of Medicare's Part D, which subsidizes prescription drug costs with federal dollars, has similarly incentivized doctors to run up the bill. A report conducted by the Department of Health and Human Services released last month found that Part D spending has more than doubled since its beginning in 2006, from $51.3 billion to $121.1 billion, and that more than 1,400 pharmacies had engaged in "questionable billing" for drugs available through Part D in 2014 alone.

A LITTLE BIT OF SUNSHINE

On July 10, 2015, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan sentenced Fata to 45 years in federal prison. Fata reportedly wept openly in court and apologized. "I misused my talents," Fata said before sentencing "because of power and greed. My quest for power is self-destructive." Later, he added that he was "horribly ashamed of my conduct" and prays for repentance. Fata also has agreed to forfeit $17.6 million.

Referencing notorious frauds like Bernie Madoff, prosecutors say that because of the lifelong destruction he has inflicted on so many, only a commensurate sentence of life in prison could come close to enacting some degree of justice. At 50, Fata is likely to live out the rest of his life behind bars.

But lawyers like McKeen and Stewart both note that the potential money available to his former patients in civil litigation is fairly low, thanks to Michigan's medical malpractice cap of about $450,000 for punitive damages such as pain and suffering (no such cap exists for economic damages like medical bills, loss of wages and future earnings).

Though there could be a joint venture by Fata's patients to recoup money from his personal earnings, according to Stewart, as of now, that money has been seized by the government. He believes that there are more than 40 civil cases pending against Fata, and that without such group efforts, it may take years before any money is awarded through litigation.

In the two years since Fata's scheme was finally brought to a halt, the government has made earnest attempts to patch up some of the holes that enable medical corruption to fester unnoticed. With the implementation of the Affordable Care Act came the Physician Payments Sunshine Act in 2014, which requires drug and medical product manufacturers who are reimbursed by federal health care programs like Medicare to report any financial payments or services they provide physicians and teaching hospitals. It's a valuable resource that allows everyone, patients included, to look in and determine if a doctor or hospital is beset by potential conflicts of interest, according to Evans.

But most think much more is needed. McKeen says that removing punitive damage caps and allowing for more transparency during internal investigations will discourage potential Fatas from stepping over the line. Swantek believes there has to be more dedicated manpower devoted to these investigations. "We shouldn't rely on the FBI to police our doctors," she says.

But any solutions will be too late for the several hundred people Fata victimized. Even after he's escorted to prison, their crippled bodies and agonizing deaths will forever serve as a testament to Fata's unchecked avarice and our institutional failure to prevent it. Asks McKeen, "Where were the checks and balances here?"

A version of this story first appeared on Medical Daily. Follow Ed Cara on Twitter @EdCara4.