Scott Davenport, a 38-year-old father and restaurant worker from Greenville, South Carolina, was, like hundreds of thousands of Americans in 2016, addicted to heroin. And his story of addiction—cycling in and out of treatment centers for years, relapsing, finding it difficult to stay sober each day—was like that of many across the country. Until it wasn't.

In 2015, Davenport had been clean for two years and was holding down a new job in a new city with a new girlfriend.

"It looked for the first time that he had turned the corner," Scott's father, Roy Davenport, tells Newsweek. "For the first time in years, things were looking up for him."

But then in March 2015 something happened. Davenport didn't just relapse. He decided to shoot heroin again and instead was sold a dose of fentanyl, the lethal opioid that can be 50 times more potent than heroin and is increasingly being sold as heroin by street dealers.

"For whatever reason, he decided one last time to go back and do what his drug of choice was, heroin, and I'm sure he thought he was buying heroin and somebody sold him 100 percent fentanyl," Roy says. "I got that phone call no parent ever wants to get. Someone from the restaurant where he was working called and said, 'I hate to be the one to call you, but we just found your son unconscious in the bathroom.'"

Scott was killed almost instantaneously by the dose of fentanyl, Roy says. His death in March 2015 was one of the early signs of a lethal new chapter in the United States' surging addiction to opioids.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opiate originally used in hospitals as a legitimate painkiller, particularly after surgeries. It began showing up laced in heroin around 2014, ostensibly to boost the high, according to intelligence provided to Newsweek by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. By 2015, traffickers were selling pure fentanyl but calling it heroin, according to the DEA.

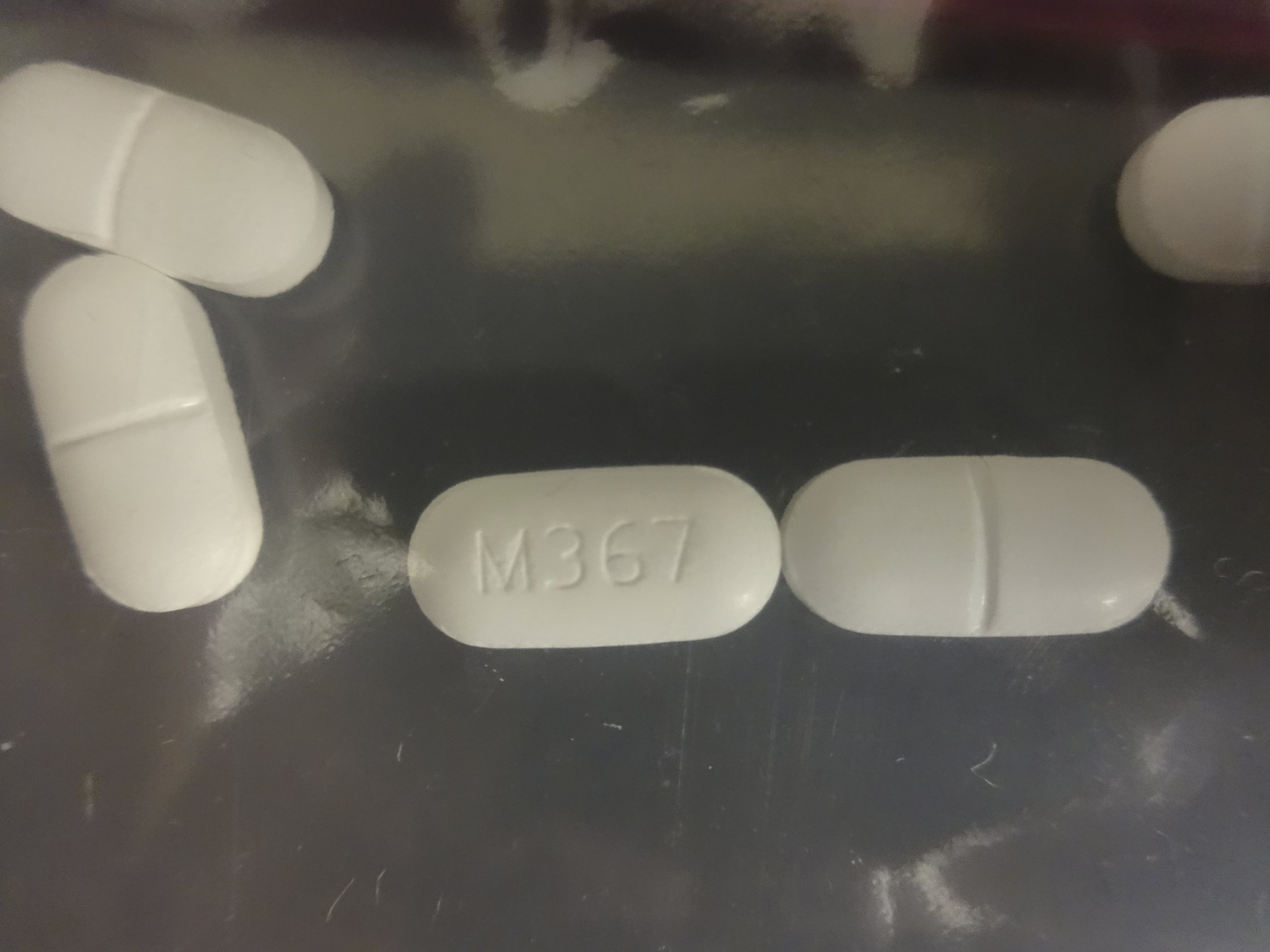

Now, fentanyl is showing up on the street in counterfeit pills being passed off as oxycodone or even Xanax, and buyers have no idea they are purchasing a synthetic painkiller more powerful than most street drugs, according to DEA spokesman Rusty Payne.

This week, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a warning about a recent rash of overdoses in Sacramento, California, and the San Francisco Bay Area that were caused by fentanyl pills sold as the painkiller Norco, an addictive pain medication that, like Vicodin, is composed of a combination of hydrocodone and acetaminophen and prescribed to treat moderate to severe pain.

Sacramento County has treated 52 patients for Norco poisoning since late March, with 14 deaths in the region, while seven people have been hospitalized in the Bay Area, according to the Associated Press.

The DEA is currently investigating the counterfeit Norco pills. According to Payne, most fentanyl-laced drugs being sold at the street level are coming into the U.S. through traditional smuggling routes from Mexico, run by the same Mexican drug cartels that ship all sorts of drugs into the U.S.

The Department of Justice announced charges earlier this month against one alleged smuggler accused of trying to cross the U.S.-Mexico border near San Diego with 1,200 pills labeled as oxycodone that were actually 100 percent fentanyl, as well as 5.4 grams of powdered fentanyl.

"It can go so much farther than heroin, and the traffickers are starting to figure this out."

Prior to being smuggled into the U.S., the fentanyl pills, powders and patches are being created in labs in Mexico or China. According to the DEA, there are "thousands and thousands" of chemical manufacturing companies in China that produce raw chemicals as well as designer synthetic drugs such as cannabinoids, cathinones, phenethylamines and fentanyl analogues, as well as chemicals for meth production such as ephedrine and pseudoephedrine.

The labs, mainly located in port cities like Shanghai, operate legitimately by fulfilling chemical orders for pharmaceutical and industrial buyers, but are able to also sell drugs to traffickers due to lax oversight and regulation by the Chinese government, according to The Guardian, which found that local officials can be bribed to look the other way and the Chinese government is not concerned with drugs being shipped abroad.

"As [the labs] have recognized this massive opioid epidemic here, we've seen a huge increase in fentanyl seizures, overdoses and abuse, just like the designer synthetic drugs," Payne says.

Once in the U.S., they are sold as tablets for $15 a pop in places like Albany, New York, or in powdered form for $40 to $65 a gram in New York City, prices that are comparable to heroin—though fentanyl is much more powerful, Payne says.

"The Mexican cartels see a huge profit margin," Payne says, noting that a kilo of fentanyl cut and sold in small amounts can generate more than $1 million in profit, compared with a $50,000 to $100,000 profit for a kilo of heroin. "It can go so much farther than heroin, and the traffickers are starting to figure this out."

The current surge of fentanyl into the street drug market first showed up in 2014 in New England states including New Hampshire, Vermont and Massachusetts, which have all wrestled with high rates of heroin addiction in recent years, Payne says. Only more recently has it arrived in California—and both California health officials and DEA officials are now investigating why. In October, the San Francisco Department of Public Health issued a warning about fentanyl-laced counterfeit Xanax being sold on the city's streets.

Fentanyl has also made it into the Canadian drug market. Authorities in British Columbia declared a public health emergency this month, citing more than 200 fentanyl-related deaths so far in 2016, according to the National Post.

Payne says that the DEA's current plan to fight the fentanyl surge is to use traditional methods to disrupt cartel operations. These include launching investigations to identify smugglers, dealers and routes, and then making arrests.

The agency also wants to warn more American drug users about the dangers of fentanyl. The DEA hosts a national pill take-back day every six months that Payne says has been "quite successful," both in urging Americans to get rid of their addictive pill supplies and as a platform for educating the public about the dangers of pills. The agency is also trying to communicate with the medical community about the dangers of prescribing the pills, he says.

In March, the CDC issued initial guidelines for limiting opioid painkiller prescriptions in light of the opioid addiction "epidemic" in the country, urging medical professionals to rely on non-opioid painkillers if possible and limiting the number of pills in opioid prescriptions.

"We're doing everything we do in terms of going after traditional drug trafficking networks. That's really what we do," Payne says.

Roy Davenport says that after his son's death, he hopes there are other measures the government can take too. He and his daughter have been pushing lawmakers in their home state of South Carolina, where Scott died, to pass legislation known as Scott's Law, which would make it possible to hold drug dealers accountable for users' overdoses. Davenport says that when he found out his son's dealer could only be prosecuted for selling drugs, and not for playing a role in Scott's death, he was shocked.

"I said wait a minute, I can get in my car after drinking, hit someone and be charged with vehicular homicide, but not the person who sold my son these drugs?" Roy says. "To me, it's homicide; it's reckless homicide or homicide by drug delivery."

They hope that penalties ranging from five to 30 years can be imposed on drug dealers involved in deaths.

"The law would send a clear message to drug dealers that if you keep doing this, you can be held accountable," he says.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.