Natalie Fitzpatrick, 29, had been through three rounds of in vitro fertilization when her doctors suggested she try immunotherapy. Each of her IVF treatments had resulted in a miscarriage, and her doctors wanted to test her to see if there was something wrong with her immune system. But nearly $4,000 later, the additional testing proved fruitless. Fitzpatrick's next two IVF cycles were unsuccessful—she miscarried once more—and she's still trying.

Testing the immune system is one of a growing number of additional services offered to couples who can't conceive through IVF treatment alone. Some clinics say they do it because certain antibodies can interfere with embryo implantation, but these claims are not backed by evidence. According to a study that appeared in the BMJ at the end of November, the same is true for many other extra services—of nearly 30 fertility clinic add-ons reviewed, only one increased a woman's chances of having a baby. That was an endometrial scratch, in which a small nick is made in the uterus's lining to increase the likelihood of an embryo implanting on it. And that had good results only if a woman had been through two previous rounds of IVF.

"People are inventing new technologies and tests to try to help, but they're not demonstrating big benefits," says one of the study's authors, Elizabeth Spencer, an epidemiologist at Oxford University's Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. "In most cases, they're not demonstrating benefits at all."

These add-ons include blastocyst culture, where the embryo is allowed to grow in the lab for five days instead of the usual three, before being transferred to a woman's uterus. Or genetic screening of embryos for possible defects so that only "healthy" ones are implanted.

Spencer and her colleagues spent a year examining the websites of all the fertility clinics in the U.K., compiling a list of procedures each clinic offered in addition to IVF. They then reviewed evidence for the usefulness of each intervention. The researchers concluded that for 26 of the 27 routinely offered procedures, there was no conclusive evidence that they improved a couple's chances of having a baby. Of the 276 claims made by fertility clinics on their websites, only 16 even cited scientific research backing up that claim.

But that may not always be the fault of clinic doctors, says New York University bioethicist Arthur Caplan. "People are willing to gamble and pay on the chance that it might add something" to their chances of conceiving, he notes. "There are very few people who are as desperate as infertile people."

This melding of ardent desires—clinics seeking a profit and patients desperately wanting a baby—has resulted in a booming business. Fertility treatment is a $4 billion industry in the U.S., where 7 million women have fertility problems.

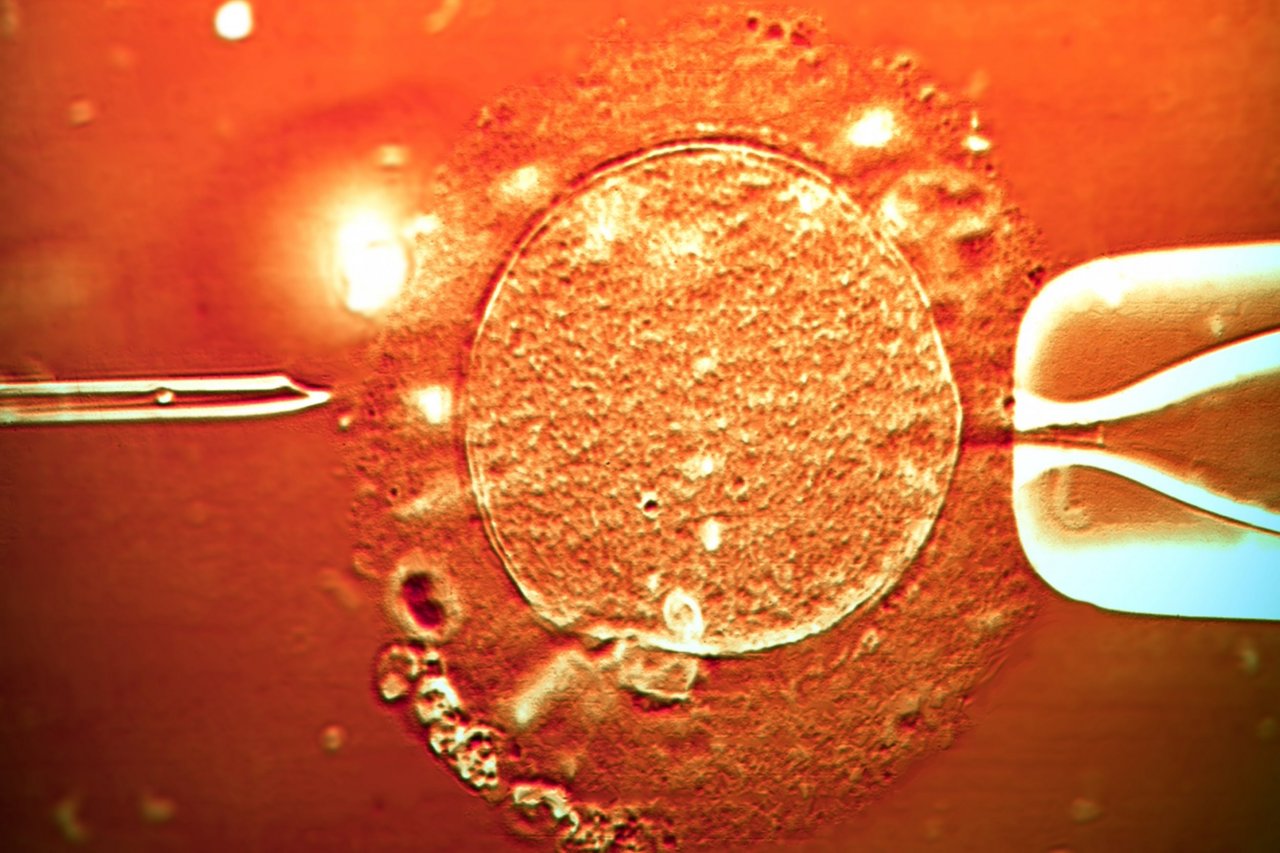

In vitro fertilization, introduced in 1978, is the most popular—and, arguably, the most successful—assisted reproductive technology. With IVF, a woman undergoes hormone treatment to stimulate her ovaries to produce multiple eggs. The eggs are then removed from her body and combined with sperm in a laboratory dish. When the eggs are fertilized and begin to grow, one or more embryos are moved into the woman's uterus. One such IVF cycle costs an average of $12,400 in the U.S., and couples typically undergo more than one cycle because IVF success rates aren't usually higher than 30 percent for women under 35 and lower for women over that age.

The new study's authors say there is an urgent need for trials to better establish that supplementary services work. But such trials are expensive and time-consuming, and there's no incentive for pharmaceutical companies or fertility clinics to run them, says Rene Almeling, who teaches sociology and public health at Yale.

One of the things clinics often do is use drugs for purposes for which they are not approved. The Food and Drug Administration is responsible for approving fertility drugs, but it can't stop approved drugs from being used for other purposes. The drug Lupron, for example, was developed to treat advanced prostate cancer. It is being used to retrieve eggs, says Marcy Darnovsky, director of the Center for Genetics and Society. Lupron lowers estrogen levels, shutting down the reproductive system before another drug is used to stimulate the production of multiple eggs.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention requires fertility clinics to report their IVF success rates each year. But it doesn't collect information on whether babies were born healthy or if their mothers suffered from the long-term effects of egg harvesting—data that experts say is much-needed. The industry "is not very regulated at all in the U.S.," Darnovsky says, "but there's not much of an appetite for [more regulation]."

If the government isn't going to regulate the clinics more closely, it's up to the patients to do their homework, says Miriam Zoll, author of the 2013 book Cracked Open: Liberty, Fertility, and the Pursuit of High-Tech Babies, in which she discusses her four failed attempts at IVF. She encourages patients to learn about fertility treatments and "speak to people who've been through it all before." Patients should look at information provided by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine, a nonprofit consisting of physicians and other health professionals in reproductive medicine. And before deciding on IVF or paying for any add-ons, they should ask whether a treatment has been adequately studied and found to be safe and effective, she says.

Fitzpatrick and her husband are preparing to undergo their sixth round of IVF and are considering other treatments, but this time, she says, "I'm going to do my homework first."