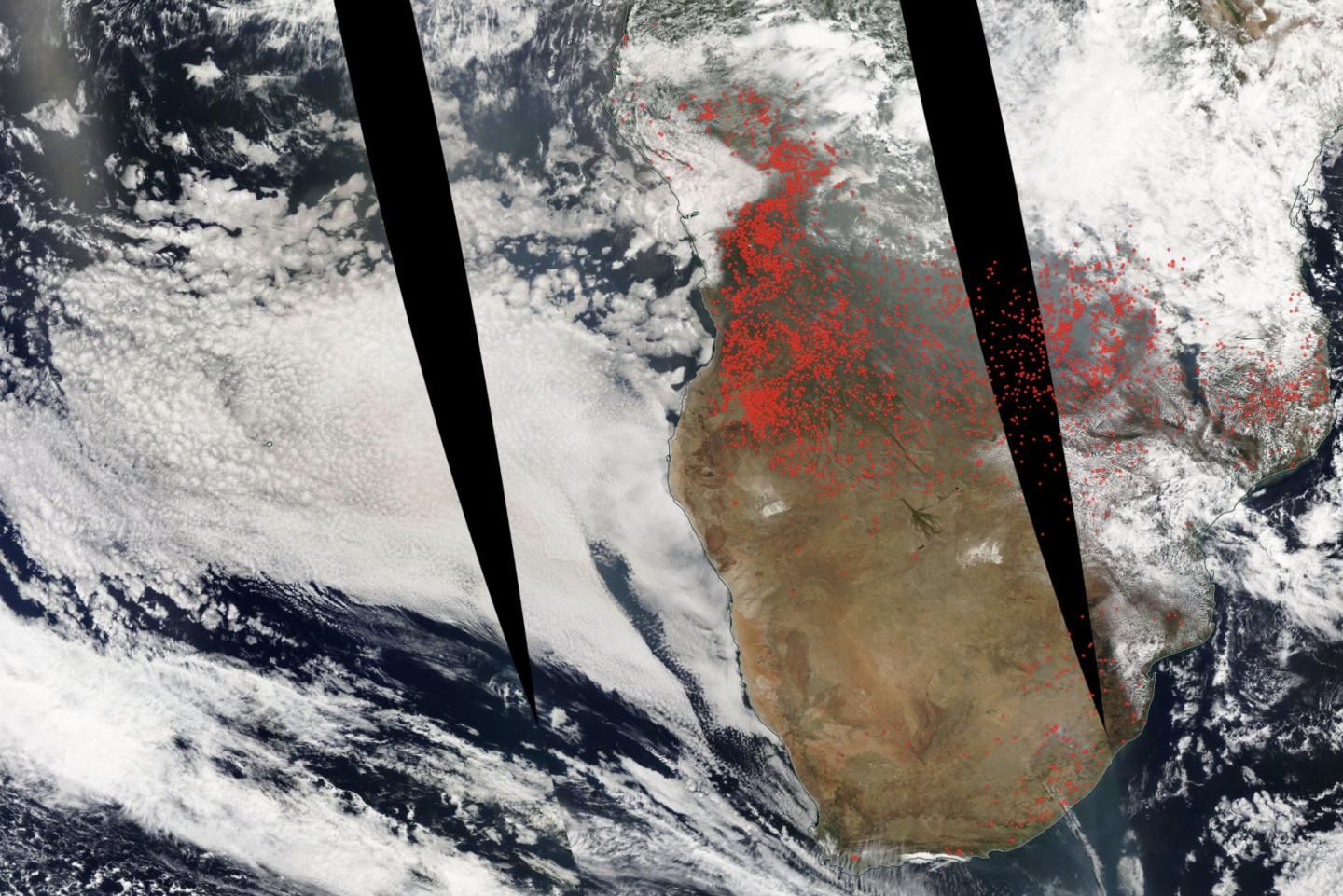

Fires in South Africa, which are so big that they can be seen from space satellites, are having an outsized effect on the world's climate, according to a new study published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science on Monday.

Researchers from the University of Wyoming found that the smoke generated by these fires drifts over the southeast Atlantic Ocean, enhancing the brightness of low-level clouds in the region. This reflects light coming from the sun, creating a cooling effect that counteracts the warming produced by greenhouse gases.

Xiaohong Liu, from the Department of Atmospheric Science at the University of Wyoming and Zheng Lu, an associate in Liu's group, made their findings by modeling the smoke and its effects on the clouds using a supercomputer.

They found that layers of smoke and clouds in the atmosphere are closer to each other than previously thought and that this accelerates the clouds' cooling effect. The reason for this is that the smoke contains tiny aerosol particles on which water vapor condenses, increasing the clouds' brightness.

This cooling effect is larger per square meter than the warming created by greenhouse gases, the researchers said. According to Liu, carbon dioxide emitted by human activities since the Industrial Revolution creates a greenhouse warming effect of 1.66 watts per square meter that is uniform across the globe.

However, the cooling effect of the smoke, in the southeast Atlantic at least, is much larger than this, coming to 7 watts per square meter during the annual fire season—which runs from July through October. Some of these fires are started intentionally to clear land, although many are wildfires.

They release huge quantities of smoke, containing aerosols, which travels westward over the southeast Atlantic, interacting with clouds located approximately 0.6 miles (1 km) above sea level.

As the aerosols mix into the clouds, the amount of water that condenses increases, boosting their brightness. This results in substantial cooling of the Earth in this region, according to the study.

The researchers hope that their latest work will help to refine global climate models by enabling them to more effectively take into account how clouds interact with aerosols emitted by various sources, including fires, deserts, power plants, vehicles and oceans.

In future, the team would also like to quantify the total cooling effect of aerosols across the globe using their computational techniques to determine whether or not this has masked the true extent of the greenhouse effect created by the emission of fossil fuels.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.