Chemicals once used to prevent furniture from burning accumulate in the bloodstream and elsewhere in the body after being ingested in dust and food. And though they've been banned for more than 10 years, they're not going away, new research shows.

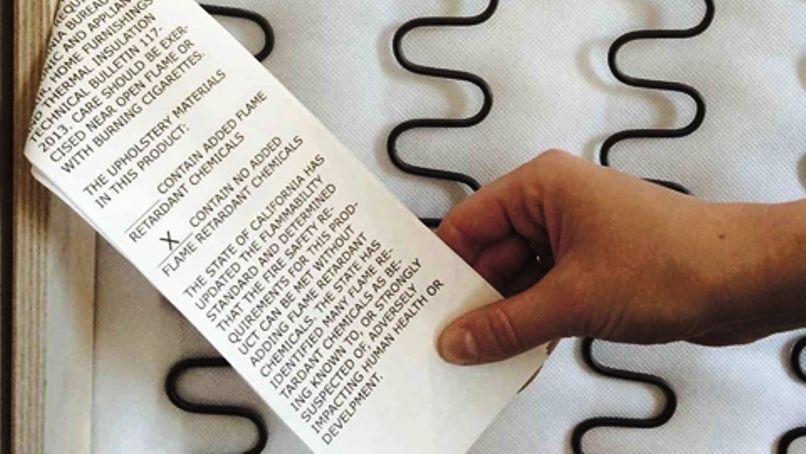

In 2006, the federal government began phasing out two types of flame retardants known as polybrominated diphenyl ethers, or PBDEs. This move followed studies showing that the chemicals were ending up in people's bodies and breast milk in increasing amounts. Mounting evidence also shows that they may interfere with the body's endocrine system and lead to neurodevelopmental problems, thyroid imbalances and other ill effects.

In the years immediately following the ban, levels of these chemicals slowly began to decline in people's houses, and likewise in people's bodies. But the new study, published in mid-March in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, suggests that bodily levels of the chemicals have plateaued over time, and even increased, in certain people.

In the paper, researchers looked at blood levels of two types of PBDEs in the blood of more than 1,250 California women between the ages of 40 and 94. The scientists found that levels of flame retardants found therein have increased slightly between 2011 and 2015.

Susan Hurley, the study's first author and a research associate with the Cancer Prevention Institute of California, suggests the chemicals may be increasingly getting into our food. Hurley says the chemicals are long-lasting, and once in the environment, they're virtually impossible to destroy. They accumulate in fat, and can make their way up the food chain. Hurley hypothesizes that as people have gotten rid of old furniture—particular items containing foam, impregnated with PBDEs—the chemicals have been spread more widely into the environment via incineration, runoff and the like.

The research "suggests these things are making their way from your couch into your food," says Arlene Blum, a scientist with the Green Science Policy Institute who wasn't involved in the study.

These flame retardants also get into the body through the indoor environment, likely through contact with and accidental ingestion of dust, where high levels of the chemicals have been found. As furniture with these chemicals has gradually been replaced, there is less in the indoor environment, Blum says. But as old couches and the like have reached landfills, their flame-retardant quarry has spread through the air and water.

A similar pattern can be seen with a troublesome class of chemicals known as polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs. These substances were widely widely manufactured until the 1970s for use as coolants and other applications, before research showed that they have many negative health effects; many are carcinogens and others interfere with the body's endocrine system. After their manufacture ceased, levels found in people's bodies declined. More than a decade later, however, they rose again in certain groups of people, after the substances migrated to the food supply.

Todd Whitehead, an assistant researcher at the University of California-Berkeley, says the study is a "really big deal" because it sends "a message about the importance of the responsible use of chemicals, especially persistent toxic chemicals" that accumulate in the body. "These things take a long time to get rid of, so we need to be more proactive about using safer products in the future."

They study was done as part of the California teacher's study, a huge research effort involving more than 130,000 current and former public school teachers or administrators, which is geared toward better understanding risk factors for cancer and other disease. As such, it wasn't designed to find out exactly how people were exposed to PBDEs, something Hurley and others hope to further explore in the future.

The study suggests the middle-aged and older women may be being exposed more than other groups of people, or perhaps they metabolize these chemicals more slowly, says Robin Dodson, a research scientist at Silent Spring Institute.

"This research, if confirmed, suggests that even if levels of industrial pollutants decline initially after a phase-out or ban, that eventually the levels plateau so that it is actually very hard to eliminate persistent pollutants such as PBDEs," says Ami Zota, an assistant professor at George Washington University's school of public health.

PBDEs are no longer used as widely as they once were. However, in many cases, companies are replacing them with similar chemicals, whose health effects haven't been well-studied, Blum says.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Douglas Main is a journalist who lives in New York City and whose writing has appeared in the New York ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.