There was an exceedingly awkward moment near the beginning of my conversation with Marianna Gatto, the executive director of the Italian American Museum of Los Angeles, which opened in the city's downtown earlier this month. We were in a second floor room of the Italian Hall, a 1908 building handsomely restored into the city's newest museum, for one of the city's oldest European communities. All around us, employees bustled, fixing stubborn digital kiosks and arranging chairs, preparing for that night's ceremonial opening. Gatto was telling me about her family, which came from Sicily and Calabria to eventually settle in Los Angeles.

"Your Sunday afternoon dinners must have been unreal," I interjected, my mind joyously summoning the kind of post-Sunday church red-sauce feast that appears in just about every film about the Italian-American experience. You know, nonna bringing out meatballs, brimming glasses of Chianti. You've seen the scene a thousand times. You know.

Gatto gave me a look.

"Not really," she said, explaining that her father was an art professor while her mother was an attorney. They raised their children in well-to-do Los Feliz, not a traditional Italian enclave like downtown or, farther east, Lincoln Heights.

I recovered from my embarrassment, but the exchange is revealing of a challenge the Italian American Museum of Los Angeles is likely to encounter: convincing visitors, whether they come from Tulsa or Bremen, that the Italian experience in the United States has been more nuanced than what has been suggested by the tropes manufactured a few miles away in Hollywood.

"Italians are kind of still fair game," Gatto said. She said a television newscaster reporting on the museum's opening made exaggerated hand gestures and jokes about eating pasta for breakfast. ("I really do, I really love pasta, I feel the inner Italian in me," the reporter tells an obviously uncomfortable Gatto.)

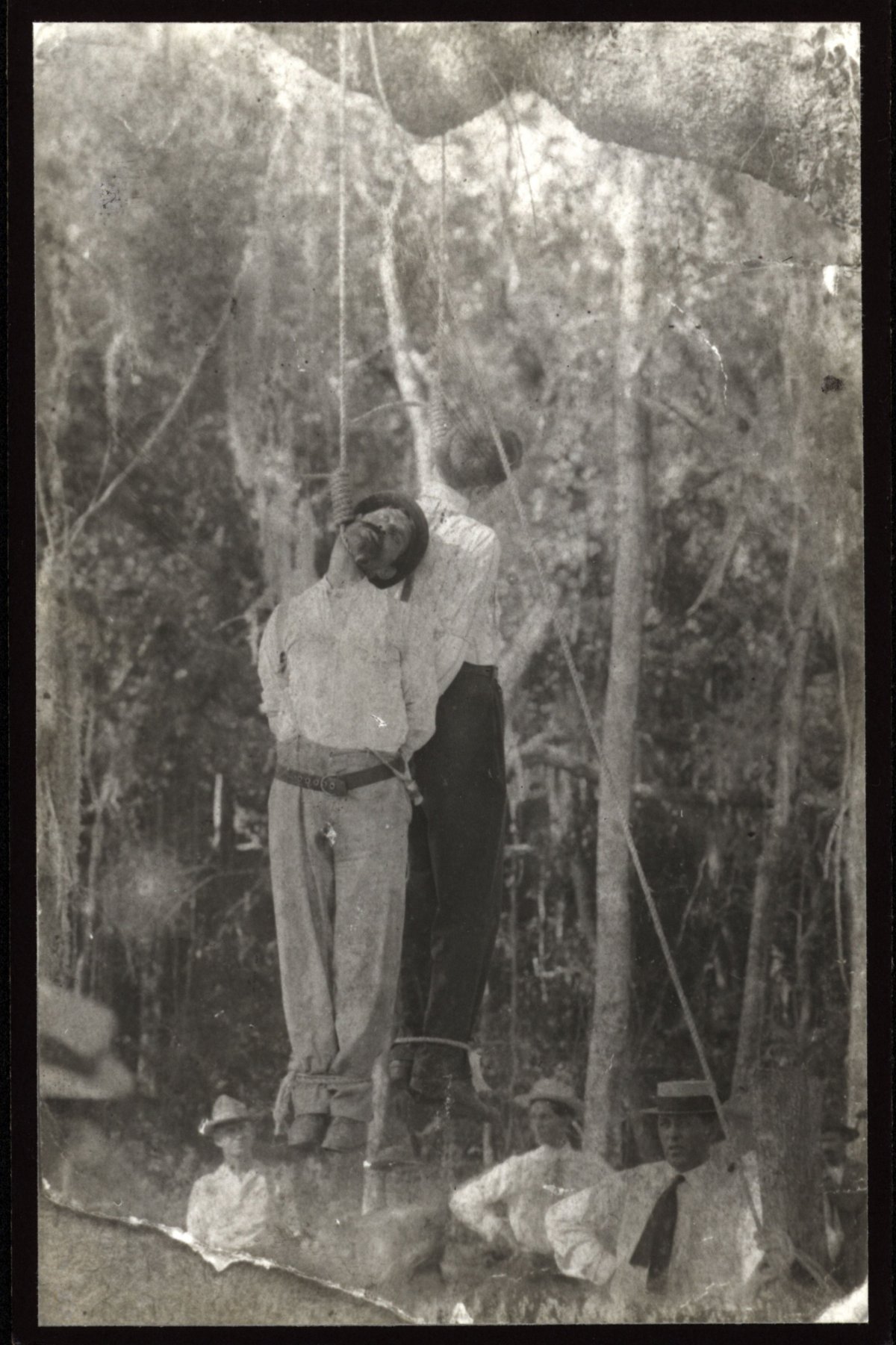

Italians have been "fair game" for well over a century. They weren't considered "white" by some American nativists who opposed mass European immigration in the 19th century. Other than African-Americans, people of Italian origin are believed by some to have been the most frequent victims of lynching. Eleven Italians were lynched in New Orleans in 1891, after the killing of that city's police chief, in what has been described as the worst recorded mass lynching in the nation's history.

The point of the Italian American Museum is not grievance, though, but complexity—not only of the Italian experience, but of the Angeleno one. The Italian Hall (which functioned as a social center until the 1950s) sits on Olvera Street, across from Union Station, the city's main train terminal. Today, Olvera Street is the heart of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, the site where a Spanish colony was established in 1781 by 44 settlers from Mexico. But at one time, Olvera Street was also known as Wine Street, in reference to the Italians who came in the 19th century and, finding themselves at home in the Mediterranean climate and prevailing Catholic culture, turned Los Angeles into an epicenter of viticulture.

"This is a chapter of the nation's history, of Southern California history, of the Italian-American diaspora, that's never been told," Gatto told me. "It's a fascinating chapter. It can reveal so much about who we are as Americans. Forget about the hyphenated American part—as Americans." At a time when immigration has turned into a threat, it is thrilling to see a museum about Italians opened in the midst of a plaza that, with its colorful stalls and food stands, can look like Mexico City. A few blocks away are the glittering red-and-gold façades of Chinatown.

"We can just change few names in the anti-Italian cartoons displayed in the Museum and we have some of the current political slogans," says Francesca Guerrini, who directs the museum's outreach and marketing efforts. A native of Milan who has been in the United States for about a decade, she says she is especially troubled by some Italians' response to the Syrian regufee crisis. The Italian American Museum is not, she points out, in the business of dictating immigration policy. Yet it can complicate entrenched beliefs about notions of belonging.

The museum holds about 6,000 items, which are displayed on the main floor of the Italian hall. Many of these are photographs and correspondences that are not showstoppers, but together they compellingly tell the story of an immigrant community different in surprising ways from its better-known East Coast counterparts, such as New York's Little Italy or South Philadelphia—or, for that matter, San Francisco's North Beach, which seems to conform more closely to our conception of what an Italian neighborhood looks like.

Many of the immigrants who came to Los Angeles left northern Italian provinces like Piedmont and Tuscany, as opposed to poorer regions like Sicily, which was the source of much of the immigration to cities like New York and Boston. And while those East Coast cities forced Italians into a How the Other Half Lives existence (lightless tenements, humid sweatshops), Southern California was too spacious, too abundant, too young, to cast newcomers wholesale into that version of urban poverty. In San Pedro, on the Pacific, arose a vibrant fishing community that, today, retains its Italian feel. Italians introduced to the New World many of the vegetables we take for granted, such as eggplant and bell peppers. And they helped make the Los Angeles area the most prolific producer of wine in California, with the Italian Vineyard Company of Rancho Cucamonga becoming the largest wine producer in the world by 1917. Few people look to the Southland for fine wine these days. Yet one of the city's historic Italian vintners, the San Antonio Winery, survived Prohibition and remains active in Downtown Los Angeles to this day.

The museum points to the uniqueness of the Angeleno experience while acknowledging the difficulties faced by Italians elsewhere. One display, for example, shows two Italians—supposed anarchists—hanging from a tree in Tampa, Florida, in a 1910 lynching. During World War II, Italian-Americans came under similar suspicion as Japanese-Americans, both seen as potential fifth-columnists in the effort against the Axis powers.

While the internment of Japanese-Americans is a well-known point of national shame, commemorated at sites like Manzanar and acknowledged by the federal government, the experience of ethnic Italians has yet to be fully recognized by American society. Italian-Americans were made to register as "enemy aliens," forced to move if living too close to sensitive areas and, sometimes, held in confinement. Gatto credits the Bay Area historian Lawrence DiStasi for making known the plight of Italian-Americans during World War II, principally through the publication of his Una Storia Segreta: The Secret History of Italian American Evacuation and Internment During World War II. If that book started the conversation, the new museum wants to perpetuate it.

The night of the museum's opening was one of those perfectly temperate Los Angeles affairs. Jazz played and wine flowed. A well-dressed crowd listened to local politicians and then trooped upstairs to view the museum itself. I spotted Angelo Mozilo, the former Countrywide Financial chief who took a good portion of the blame for the 2008 financial crisis: Mozilo grew up in New York City, the son of an Italian immigrant, but has long been a resident of Los Angeles.

"Angelenos, Southern Californians, really don't know their history," Gatto had told me a few hours before. Yet here they were, downtown, on the very spot where Giovanni Leandri became the first Italian to settle in the city nearly two centuries ago. I doubt that many of the well-heeled attendees lived anywhere near the museum. Maybe their parents had, or their grandparents, but their progeny had likely been able to move away to Pasadena or Thousand Oaks, somewhere comfortably American, somewhere with a pool. And now there were new immigrants coming to Los Angeles, from Laos, Honduras, Yemen. They are just as hungry as the Italians and Irish and African-Americans and others who came before them, and sometimes just as maligned and misunderstood. Most of them have come to the United States with a simple goal. Work hard enough, and you can move to the Valley. Stay long enough, and you can build a museum.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national affairs.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.