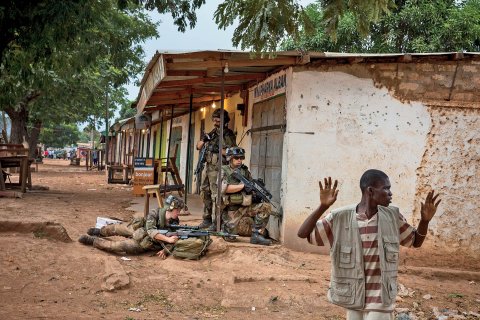

The funeral of French Foreign Legion Sergeant Marcel Kalafut was held in May at Camp Raffalli, his regimental headquarters in Calvi, Corsica. The 26-year-old was killed when his vehicle hit a land mine during a covert operation in northern Mali.

France's minister of defense, Jean-Yves Le Drian, paid tribute to the young noncommissioned officer, saying he had "died for France," and posthumously awarded him France's most valued medal, the Légion d'Honneur.

Kalafut was the eighth French soldier killed in combat in Mali since French forces intervened in January last year. The ninth, also a Legionnaire, was killed in July. At Kalafut's funeral, Le Drian said 1,000 French soldiers would remain in Mali and 3,000 in the Sahel-Sahara zone "for as long as necessary."

More than 50 years after granting its colonial empire independence, it seems Paris cannot keep its nose out of Africa. French military engagement there is much more wide-ranging than just battling Islamist insurgents in Mali. French forces are active in at least 10 African countries. In May, the government detailed plans to reinforce them, with regional centers in Chad, Burkina Faso, northern Mali and Côte d'Ivoire.

Along with the 2,000 troops France has sent to help restore order in the chaotic Central African Republic, more than 5,500 are tasked with fighting armed terrorist groups, intelligence gathering, training the local military and providing rapid reaction forces. A nongovernment source estimates that France has 10,000 troops stationed in Africa.

A confidential French Senate report recommends that the special forces' strength be boosted by 25 percent, from 3,000 to 4,000. "They constitute an appropriate response to conflicts France will probably face in the next 10 years," the authors concluded. Again, the focus was on Africa.

You could be forgiven for thinking this sounds like a 21st century remake of Beau Geste, the ripping yarn about honor and heroism in the French Foreign Legion. Same desert, same sand, same godforsaken outposts. And even some of the same opponents, such as the rebellious Tuareg nomads still battling for autonomy.

This time Paris justified military intervention in Mali—after the country's northern half had been overrun by an uneasy alliance of Tuareg rebels and Muslim extremists of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb—by saying it was invited by the beleaguered government and was acting with U.N. Security Council approval. But the intervention was less about derailing the Tuaregs' bid for autonomy than containing militant Islam amid fears that the Sahel region will become a breeding ground for Al-Qaeda terrorism that could spill into France and the rest of Europe.

The French national defense strategy outlined last year stressed the importance of "Europe's neighborhood"—the zone from Mauritania to the Horn of Africa. African countries have a "low capacity" to control their own territories, the paper said, and fragile countries risk becoming safe havens for terrorists.

A decade before, the U.S. was saying much the same thing. In the aftermath of 9/11, Washington launched "the Trans Saharan Counter-Terrorism Initiative" to train local forces in nine Saharan and sub-Saharan countries and establish semipermanent U.S. bases in each.

Since then, Washington's interest in military involvement in the region has cooled. "The U.S. has little appetite for large-scale military operations in Africa. The NATO intervention in Libya confirmed President Obama's reluctance to send troops to Africa," Amadou Sy, an analyst at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C., told Newsweek.

The U.S. appears content to have France take the lead. A Washington Post article jointly authored by Obama and François Hollande during the latter's state visit to the U.S. in February said, "Nowhere is our new partnership on more vivid display than in Africa." The two presidents declared, "Across the Sahel, we are partnering with countries to prevent Al-Qaeda from gaining new footholds."

France shares Washington's concern about militant Islam, not least because it has a large Muslim population and is close to Africa. But Paris's vigorous engagement there is also about bolstering French preeminence in a region from which it has profited hugely and hopes to profit in future.

The French economy is in the doldrums, while African economies are mostly healthy and growing. France has extensive interests in Africa, in oil, minerals, infrastructure projects, telecoms, utilities, banking and insurance. But its market share is being eroded by competition from China, Brazil, India and others.

The 21st century scramble for Africa quickened in early August when Washington hosted a three-day business summit with 50 African leaders. Obama told them, "The United States is determined to be a partner in Africa's success" and announced $33 billion in public and private commitments.

France launched a similar initiative last year. A Ministry of Economy, Finance and Industry document published in December 2013, "A Partnership for the Future," explores how France can compete. Hollande said last year he wanted to double trade with Africa within five years, creating 200,000 jobs in France.

"The Africans don't want only the Chinese. They're a little afraid. It's up to us. We must be more dynamic, more competitive," says Hubert Védrine, France's minister of foreign affairs from 1997 to 2002, who led the team that wrote the document. "France is the only country that didn't abandon Africa after independence. At the request of great leaders at the time, we stayed, to guarantee security."

That's the official line. Here's the backstory.

France's 'Civilizing Mission'

Adopted by President Charles de Gaulle in the late 1950s, the plan was to maintain close links with two dozen mostly francophone countries in France's African empire after independence. France undertook interventions to prevent wars and quash coups and insurrections. Naturally, Paris wanted to safeguard its own interests. For example, one-quarter of France's electricity is generated with uranium from Niger.

Moreover, continued influence in Africa would bolster France's faltering status as a world power. If not Africa, where?

The policy, known as "Françafrique," was managed from the Élysée Palace, the seat of the president, by an "Africa cell" that operated in the shadows, via personal contacts and an undercover networks of spies, the military, big business, the Corsican mafia and mercenaries, without parliamentary oversight or approval.

To date, the French have made more than 40 overt military interventions in Africa, often to protect leaders they like and remove those they don't. For some African leaders, good relations with the Élysée Palace is life insurance. Many wanted to show their gratitude and ensure that the French gendarme showed up the next time he was needed.

Robert Bourgi, a Franco-Lebanese lawyer born in Senegal who was the Élysée Palace's unofficial go-between with African leaders for almost three decades, claims he delivered bags of cash from African leaders to senior French politicians up to and including President Jacques Chirac, who left office in 2007.

After numerous scandals, recent French presidents have promised to end Françafrique. President Nicolas Sarkozy shut down the Élysée Palace's Africa cell. But he chose his own advisers, including Bourgi; kept control over African policy; and deployed troops there four times. In October 2012, Hollande pledged to end Françafrique for good, promising transparency and more equal relationships.

The four military interventions during Hollande's first two years in office have been less opaque: Paris consulted with and invited the participation of African allies, the U.N. and the European Union. But African forces are ill-trained, ill-equipped and largely ineffective. The U.N. is ponderous and slow to act, and European allies are willing to commit only token forces.

Thus, argues Paris, this is not the Françafrique of old, when France did as it pleased. Now French troops react quickly to contain problems when other countries are unwilling or unable.

The nongovernmental organization Survie, which has focused on French mischief in Africa for 30 years, is not convinced. "Yes, now France waits for a U.N. mandate. But we consider that this is an alibi. France writes the resolution and proposes it. Moreover, France goes beyond the mandate," Survie President Fabrice Tarrit told Newsweek.

'Stinks Like a Rotten Fish'

Eyebrows were raised when Hollande received a parade of African dictators at the Élysée Palace, starting with Gabon's Ali Bongo in July 2012, less than two months after Hollande became president. The warm welcome was interpreted by critics as French tolerance of undemocratic regimes.

Jeremy Keenan, a professor at London University's School of Oriental and African Studies, is in no doubt. "Françafrique is alive and well," he told Newsweek. "They have to say it's dead. But it still stinks like a rotten fish!"

Among Hollande's closest advisers is his chief of staff, General Benoît Puga, who boasts decades of African experience, including front-line combat. "Hollande didn't want a ground operation in Mali," Jean-Pierre Bat, author of a book on Françafrique, told Newsweek. "But Puga told him, 'We must go in fast.'"

The French military action in Mali in January last year was swift and successful. The advance by Islamists and Tuareg rebels on the capital, Bamako, was halted, and they were forced out of Timbuktu and other towns in the north.

A month later, Hollande visited Mali and declared he had just lived through "the most important day of my political life." At home, opinion polls reported he was the least popular president in more than 50 years. Yet a Brulé Ville et Associés poll reported that three-quarters of the French approved of his Mali intervention. It was the best news he'd had in months.

"A few years ago, François Hollande attacked Françafrique. He held his nose," Bourgi told the website Mondafrique. "In Mali, he took a liking—and the word is not strong enough—to Africa."

There is no denying Hollande's enthusiasm. On top of his frequent visits to Africa, in May last year he was the only Western leader to attend the African Union summit in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

And in May this year, after the abduction of more than 200 Nigerian schoolgirls by the Islamist group Boko Haram, Hollande was the first Western leader to convene a summit of concerned African leaders.

For Hollande, it was a chance to show his decisiveness on Africa in a story grabbing the headlines around the world. Most of the girls are still missing, despite offers of help from France and others. Still, the Paris summit declared war on Boko Haram, and, soon after, the U.N. and the European Union designated it a "terrorist group."

In July, the defense ministers of Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad and Niger pledged to speed up the creation of a 2,800-strong regional force to deal with the group, each contributing 700 troops. The four nations have yet to resolve who should fund and command the force.

According to Francis Laloupo, author of the book France-Africa—Out Now?, "Some African leaders are schizophrenic, asking to break with France one minute and needing its support the next." Mostly, though, anxious autocrats and presidents-for-life are happy to have Paris pacing the block.

In South Africa, which has the continent's most effective military, "there is unease about external actors' involvement in African affairs. There's a view that parts of francophone Africa are not yet independent," said Alfredo Tjiurimo Hengari of the South African Institute for International Affairs in Johannesburg. "South Africa's push for 'African solutions to African problems' is a consequence of the corrosive presence of the French gendarme in Africa."

Still, Hengari said that so long as African forces are incapable, "the French are likely to remain the leading gendarme in Africa conflicts." And for Paul Melly of the London think tank Chatham House, "Africa is the only place where France is a major player."

It's almost as if Beau Geste had never gone away.