The guards standing outside the entrance to the Radisson Blu Hotel in Bamako, the capital of Mali, didn't have time to react. Around 7 o'clock on the morning of November 20, at least two baseball-cap-wearing men in their early 20s used automatic rifles to gun down the security men, then dashed up 12 steps leading into the lobby. Moments later, a second burst of gunfire rang out.

"We could hear gunshots and people screaming," says Mukesh Chellani, an Indian business development manager who works in Mali. A resident of the hotel for the past 15 years, he and 19 other colleagues were at the back of the building when they heard the shots. Terrified, they looked for anything that could protect them from the gunmen's bullets. "We barricaded the door from the inside with cupboards and tables," Chellani says.

The attackers burst into the breakfast room, which was filled that morning with the usual assortment of diplomats, Air France crew members, contractors and development officials. More than a dozen people desperately tried to squeeze inside an elevator, which holds eight; as it stalled, its door opened and a gunman raked those inside with machine gun fire. The gunmen freed the captives who could recite verses from the Koran and held the rest.

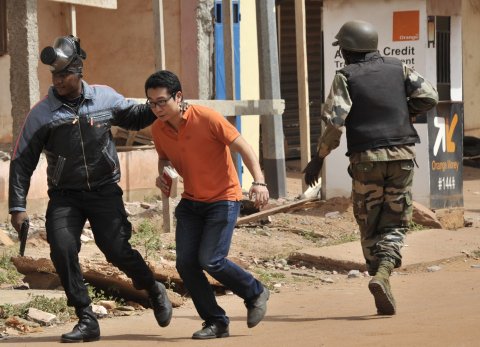

The standoff finally ended when troops stormed the hotel, killing the gunmen and releasing the survivors. The final death toll: 19 victims and two gunmen. (Some witnesses say they saw more than two gunmen, but three days after the attack, only two bodies had been found.)

The war against Islamist militants in Mali was supposed to be long over. Less than three years ago, President François Hollande of France launched Operation Serval, a military campaign aimed at rooting out about 1,000 fighters belonging to the region's Al-Qaeda affiliate—Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb—and an assortment of other groups that had captured the north of Mali in early 2012. French forces chased the radicals out of Timbuktu and other towns, then fought them in a desert valley near the Algerian border. Several hundred jihadis were killed in one week of fighting in February and March 2013. "We went cave by cave, and we killed almost all of them," I was told in 2014 by Captain Raphäel Oudot de Dainville, a French officer who commanded a company of the Foreign Legion in the valley. Clearly, some survived.

For Mali, the assault on the Radisson was the clearest sign yet that an Islamist force that seized a large part of the country—or its sympathizers—remains a threat. But the Bamako attack was also a significant strike against a more distant, and recently wounded, enemy of the Islamists: France. The country that once controlled Mali as its colonial overlord is still reeling from the November 13 Paris attacks by adherents of the Islamic State militant group (ISIS), which left 130 people dead. The storming of the Radisson one week after those killings appears to be part of the cost France has been paying for its recent attempts to take a leading role among Europe's cautious nations in trying to fight chaos and extremism in the Middle East and parts of Africa.

"France is now perceived as being at the heart of a crusader alliance, which means they are now a target for terrorist attack," says Raffaello Pantucci, director of international security studies at the Royal United Services Institute, a London-based defense and security think tank.

French fighter jets played a pivotal role in assisting Libyan rebels in their revolution against President Muammar el-Qaddafi in 2011, a victory that has soured as the country has split into territory controlled by warring factions. Next came the French intervention in Mali—another apparent victory in what seemed like a newly aggressive French foreign policy. In September 2014, France was one of nine countries to join a U.S.-led coalition whose goal is to defeat ISIS.

Hollande, however, shows no signs of backing away from the fight against the Islamists, promising on November 23 to "intensify" France's attacks on ISIS. After the Radisson siege, he said, "Once again, terrorists want to make their barbaric presence felt everywhere—where they can kill, where they can massacre. So we should once again show our solidarity with our ally, Mali."

The attack on the hotel was the seventh such attack this year in Mali. The probable architect was Mokhtar Belmokhtar, a one-eyed Algerian who fought as a holy warrior in Afghanistan in the 1980s and orchestrated the 2013 siege of an Algerian gasworks in which dozens died. Al-Mourabitoun — or, the Sentinels — the militant group he founded in 2013, claimed credit for the Radisson attack. (Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb also claimed responsibility.)

What has gone wrong? Excessive optimism on the French's part, the resilience of hardened killers, the difficulties of establishing security in a remote desert environment and poor governance in a destitute nation with few resources have all provided Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and its affiliates plenty of room to regroup. The return of Mali's Islamist militants to the forefront is a reminder of the challenges of waging war against Islamist radicals who often blend easily into their environments, have no compunction about attacking soft targets and are ready to sacrifice their lives for jihad.

In reality, the French were never able to pacify the north. In 2014, I spent 24 tense hours in Kidal, a mostly Tuareg town in Mali's far northeast, weeks after Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb militants kidnapped and murdered two French radio reporters there. French troops had never secured this sand-swept outpost, and Al-Qaeda bided its time, waiting for the opportunity to reorganize and strike again.

Despite the continued insecurity, the French were highly sensitive to being perceived as an occupier of their former colony. Today, 1,000 French troops are left in Mali, down from a peak of 2,500 at the end of Operation Serval. In 2014, France transformed its mission into a regional program, Operation Barkhane, headquartered in Chad. "It further diluted the French presence in Mali," says Corinne Dufka, head of Human Rights Watch's West Africa desk.

The U.N. Security Council established a Mali peacekeeping force in April 2013, with a mandate to help stabilize the country—but that mandate does not include counterterrorism operations, which fall to the Malian military and the remaining French forces. Regardless of their intended mission, t he U.N. blue helmets end up facing militant attacks. They suffered 29 fatalities in Mali in 2014, the largest number of deaths for a U.N. peacekeeping mission that year, and 10 have been killed in 2015. "No mission has been as costly in terms of blood" than the U.N. force in Mali, said Hervé Ladsous, undersecretary-general of U.N. peacekeeping, in January.

The Malian army has barely been a factor in the battle against extremists. In early 2012, despite years of training by U.S. special forces and Navy SEALs, the army quickly collapsed before the militants' offensive. Since Operation Serval, the European Union has spent $29.4 million on extending a training program for the troops, which one Malian cabinet minister once described to me in 2014 as "the dregs of society —all the problem children, failures in school, delinquents and criminals." That same year, Didier Dacko, commander in chief of the Malian armed forces, told me that "esprit de corps does not exist."

Meanwhile, the Islamists appear to be growing in number. In January 2015, the ill-equipped Malian troops began having to seriously contend with a new Islamist group, the Macina Liberation Front, based around central Mali. The group has attacked villages and military posts in the center of the country and along the borders with the Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso.

The biggest failure, though, in the wake of Operation Serval's apparently quick win, has been France's inability to kill Belmokhtar, who slipped into the Sahara with a small band of loyalists as French forces advanced in January 2013. For the past three years, he has moved at will across the Sahara with a few dozen followers in pickup trucks. In December 2012, he split from Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb—the group's leaders in Algeria accused him of disregarding their orders—and created a spinoff group, which carried out the Algerian gasworks attack.

Last year, Belmokhtar merged his band of fighters with a gang of Mauritanian and Malian jihadists called the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa, creating Al-Mourabitoun. In March 2015, Al-Mourabitoun gunmen shot dead five people at a café in Bamako. Three months later, two American F-15 fighter jets dropped 500-pound bombs on a gathering of jihadis in the Libyan coastal city of Ajdabiya and claimed they had finally killed Belmokhtar. But a jihadi representative insisted that the bomb missed Belmokhtar and that no DNA evidence has been presented to confirm his death.

In August, in an operation that appears to have prefigured the November 20 attack in Bamako but passed without receiving much notice from the outside world, gunmen invaded the Byblos Hotel in the central Mali town of Sévaré. Government forces invaded the hotel after a long standoff and freed hostages; four Malian soldiers, five U.N. workers and four attackers were killed. Fighters linked to Belmokhtar claimed responsibility, but troops found identification on the attackers' bodies that identified them as belonging to the Macina Liberation Front—a worrying sign of increasing collaboration between Mali's myriad Islamist groups.

The Radisson attack has realized the worst fears of Mali watchers. "What had been touted as the turning point for better stability has now been brought in question," says Human Rights Watch's Dufka. Hollande pledged to provide "necessary support" to Mali after the siege, b ut with France ramping up its struggle against ISIS, Mali's former colonizer is now facing the unpalatable prospect of refighting a war it never really finished.

Joshua Hammer's book The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu: And Their Race to Save the World's Most Precious Manuscripts will be published in April 2016.