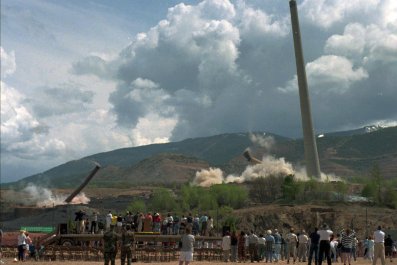

The video went viral almost instantly, and for good reason. A corporate executive—Chris Nelson, president of Carrier, a subsidiary of United Technologies that makes air conditioners—stands in front of a large group of workers at the company's plant in Indianapolis in February. He tells them the factory is closing and moving to Monterrey, Mexico. There are shouts of anger and obscenities. Fourteen-hundred people who had well-paid full-time jobs are learning that it's all over. At one point, with a straight face, Nelson says, "I want to be clear, this is strictly a business decision"—as if it could have been anything else.

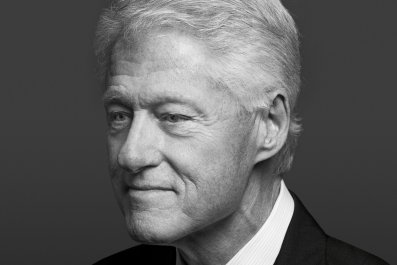

It went viral because it encapsulated the fracturing of the free trade consensus in the United States, the mounting backlash against economic globalization and the political heat that trade deals, past and present, have drawn during this year's presidential campaign. On the night of the last primaries, presumptive Republican nominee Donald Trump repeated his standard riff about the evils of bad trade deals, vowing that "the American worker will have his or her job protected from foreign competition." And while Hillary Clinton has been less strident about trade than her Democratic rival, Bernie Sanders, who during the campaign repeatedly linked the decline in manufacturing employment in the U.S. to "failed trade policies," the former secretary of state now says she opposes the Obama administration's Trans-Pacific Partnership—a pending free trade deal with 11 Asian nations negotiated while she was head of the State Department.

The collapse of the free trade consensus in the United States has been stunningly swift, driven in part by the rise of China and by the persistence of massive annual bilateral trade deficits with Beijing. The segment of the Democratic Party supported by organized labor that has always been protectionist has now been joined by Trump. His shocking takeover of the Republican Party has been driven largely by his opposition to trade agreements the party used to routinely support. Many Trump supporters—not to mention his fanboys and girls in conservative media (see Sean Hannity or talk radio host Laura Ingraham)—typically describe themselves as "Reagan Republicans," but the late president was an arch free trader, while today Trump's supporters behave as if they've been possessed by the spirit of Richard Gephardt, the former House majority leader who ran for the Democratic presidential nomination twice on protectionist platforms—and failed both times.

This political hostility toward free trade is all the more striking because the vast majority of economists, whether they lean left or right, agree that open trade is a net economic benefit for any country that practices it. Indeed, there may still be a bigger consensus on this than on anything else in mainstream economics.

The question then is: Who is right? Are the trade deals that Trump has turned into epithets bad for the country? Critics of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the 1993 trade and investment pact ratified by the U.S., Canada and Mexico, or of China's accession to the World Trade Organization ( WTO) in 2001, which the U.S. championed, argue that allowing unfettered imports from low-wage countries (like China or Mexico) puts the U.S. and its manufacturing workers in a "race to the bottom." Trade critic Alan Tonelson says it's a race that we can't win, given how much more a U.S. industrial worker earns than his or her counterpart in, say, China's Yangtze River Delta. From this, critics contend that bad trade agreements have led to the decline of U.S. manufacturing employment—down 30 percent since 2000—as well as stagnation in manufacturing wages and, because of persistently large merchandise trade deficits (which decrease gross domestic product), the overall sluggish pace of U.S. economic growth.

Make no mistake: NAFTA, China's admission to the WTO and a raft of free trade agreements with a range of countries (20 over the past 30 years) have been disruptive to individual companies, industries and communities. NAFTA, which was intended to increase trade and investment among the three countries involved, does make it easier for a company like Carrier to up and move to Mexico, leaving its Indiana workforce high and dry. The political potency of that is real.

Far less clear is whether the economic arguments against the trade deals the U.S. has executed stand up. Consider NAFTA. In its first decade, as investment flows increased among the three countries, with more capital leaving the U.S. and heading to Mexico and Canada than the reverse, the employment impact was less significant than today's political debate would have you believe. On an annual basis, depending on who is counting, NAFTA-related job losses in the U.S. ranged from 60,000 to 190,000. Assume for argument's sake that the upper range of those estimates is the right one: that the U.S. lost 1.9 million jobs in the decade after it was ratified. Over the same period, the U.S. economy created 34 million jobs, Canada created 3 million, and Mexico 10 million. "In the grand scheme of economic forces, NAFTA has been no more than a blip on the U.S. employment picture," says Gary Clyde Hufbauer, an economist at the Peterson Institute for International Economics who has written a book on NAFTA.

What about wages, though? Free trade critics say trade deals like NAFTA put downward pressure on manufacturing wages in the U.S., as employers hold the possibility of moving to Mexico (Carrier) over workers' heads, forcing them not to ask for wage increases. In his book, Hufbauer examined the relationship between trade and wages and found that there was not a material difference in U.S. wage rates between industries with a large volume of imports from Mexico and those with a small volume.

So NAFTA does not seem to have made a significant difference when it comes to stagnant wages. Hufbauer, though hardly a Trump supporter, is honest enough, however, to acknowledge something else: "By far the most important channel by which Mexico influences U.S. wages is via immigration, legal and illegal."

What has helped make expanding trade with China and Mexico so controversial is that the U.S., in the wake of the trade deals, didn't focus on what the fallout would be in specific communities. Hufbauer calls trade adjustment assistance in the U.S. "meager." The average worker who lost his or her job due to import competition or a factory moving to China or Mexico receives weekly income maintenance payments that amount to about 70 per cent of a displaced worker's previous income, and they are eligible for retraining programs funded by the program. Its total cost in fiscal year 2013 was only $756 million, and the Trans-Pacific Partnership includes more generous benefits for workers under trade adjustment assistance. Unfortunately for free trade advocates, the agreement appears dead in the water if the rhetoric of the two presumptive presidential nominees is to be believed.

Free trade deals, even in relatively normal political climates, are often difficult to defend. That's because their benefits are diffuse, spread throughout the economy in ways that are not nearly as visible—or powerful—as when a company executive tells a plant full of workers their jobs are headed to Monterrey or suburban Shanghai. But the reason trade remains relatively uncontroversial among economists is that the benefits are there.

Economists Lindsay Oldenski and Theodore Moran examined U.S. household consumption in industries most exposed to trade competition: clothes, footwear, food, electronics and other home goods (the study did not include industries like autos and steel, which have also been deeply affected by trends in international trade since the 1970s). They found that the share of family spending on the products included in the study has steadily declined. In current dollars, 34 percent of an average family's overall annual spending went to those items in 1973—way before NAFTA, or China's emergence as a trading power. By 2013, the spending declined to 20.2 percent—an extra $8,156 for every family to save or spend on other things. This doesn't mean, moreover, that families have cut back their purchases of clothes or electronics. On the contrary, the amount of stuff families are buying in those categories has increased—and still they're paying less.

That result is, of course, directly connected to the expansion of trade and, in particular, to the rise of China, which accelerated hugely after it joined the WTO. Trade hawks deride this phenomenon as simply the "Wal-Mart" effect, as if it were meaningless. It's not. Another economist, Edward Gresser, looked specifically at families earning no more than $35,000 and found that the amount of money spent on the categories Oldenski and Moran looked at has actually fallen faster over time for less-affluent families than for richer ones. The facts are inescapable: "Poorer and middle-class families win from globalization as consumers," says Hufbauer.

Trump and his media devotees dismiss this—they appear impervious to facts—and focus solely on the employment side of the trade equation. People are losing jobs or not getting raises because of trade, which is why we need to "bring back" jobs from Mexico and China. But again, the facts are the facts: The churn in the labor market of an economy as large as the United States is big—there are some 16 million to 18 million people laid off, rehired and hired for the first time each year, depending on where we are in the business cycle. Of those job changes, just 2 to 3 percent are linked to import competition or export expansion, according to a study by the Peterson Institute.

Estimates show that the passage of the Trans-Pacific Partnership won't do much to alter those numbers. The fact is, restricting trade will have large negative consequences, in particular among the low- and middle-income families, the ordinary Americans in whose name Clinton and Trump claim to be running. If only we were having an election in which facts mattered.