The FDA has approved the first-ever digital pill, a version of the antipsychotic medication Abilify that will allow patients to send data about when and if they take their pills to their doctors. The pill comes with an ingrained sensor that operates based on the same principles as a potato battery. It may be the first of its class, but it's unlikely to be the last.

"I think it would be a bit of a stretch to say that this would be, in the next five years, in every medication. I don't think that's realistic. I think you could say 20 to 30 years from now, that's a possibility," Andrew Thompson, the co-founder and CEO of Proteus Digital Health, which makes the sensor, told Newsweek.

In theory, digital pills may help tackle the perennial challenge of getting people to take their medications as they are supposed to. (Even people who probably think about adherence more than the average person sometimes slip up. "I just remembered, I need to take one this morning," Thompson said during an interview.) Only about 30 percent of the pills prescribed in the United States are taken as they're meant to be, and only 20 percent are refilled correctly. It's a problem for patients with a wide variety of conditions, as one study found. And, as the American College of Preventive Medicine notes in a clinical reference guide to medication adherence, "patients with psychiatric disabilities are less likely to be compliant."

The sensor itself got FDA approval in 2012, and it's been used before as a stand-alone pill that people can take along with their other medications, including blood pressure and diabetes pills. But this is the first time it's actually been applied to a drug. Abilify, an antipsychotic, is used to treat bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and, less often, depression. It is made by Otsuka Pharmaceutical.

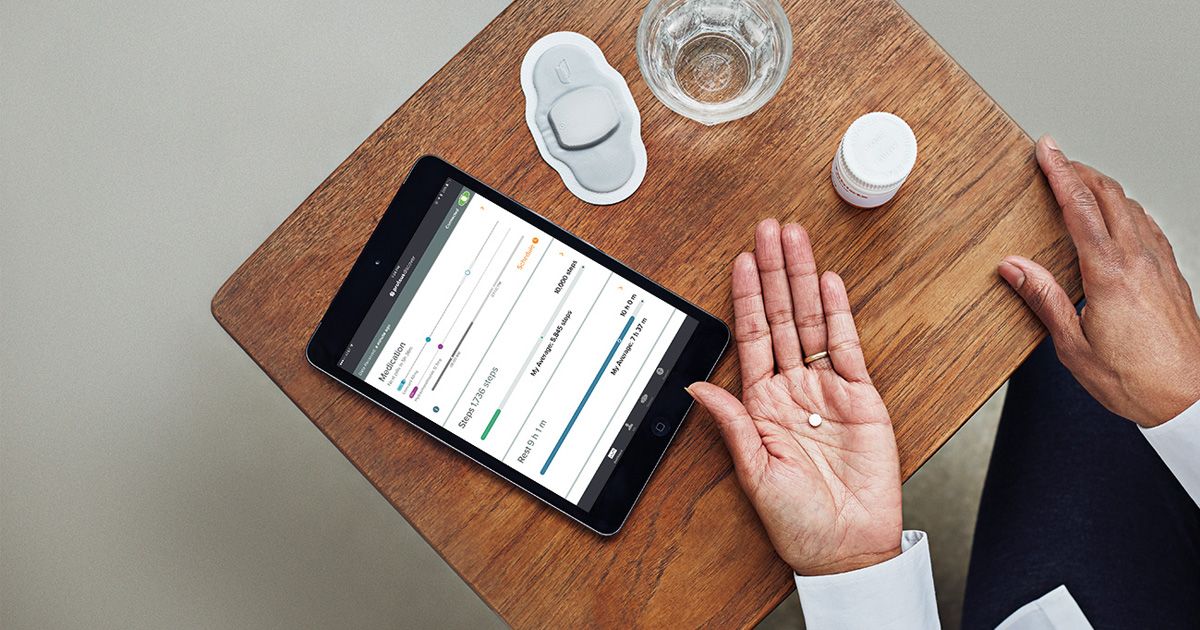

The sensor works for the exact same reason that you can use a lemon or a potato to power a light bulb. "When I'm explaining this to folks, I say it's just like a potato battery—and when you swallow the medicine and the sensor, you are the potato," Thompson said. Stomach acid can make the metals of the sensor exchange electrodes and create an electrical signal in a process called an oxidation-reduction reaction. That signal gets picked up by a patch the patient wears on his or her skin, which must be changed weekly.

The patch "filters and decodes" the signal, which is a string of numbers that's specific to an individual tablet. "When we go look up the number, we can say that the patient just swallowed Abilify MYCITE," Thompson said. Information about the dose and the manufacturing batch of the medication is also transmitted. The specificity of the signal means that, in theory, "if you swallowed three pills, we could detect all three." Finally, the patch sends a signal to a phone over Bluetooth.

The pill gets processed by the body in the usual way. And, as with everything that goes in, the sensor must go out.

It's very cool science—and if it makes a dent in the adherence problem, that could be huge. "In the context of the mental health patient, maladherence can lead much more quickly to very, very serious consequences," Thompson said. "This is a community that disproportionately benefits from this kind of solution."

Preliminary data from studies for blood pressure and diabetes meds indicated that the drug with the sensor helped patients more than the drug that didn't have it, Proteus said in April 2016—perhaps because patients were better at taking meds on time, though Thompson cautioned against speculating about the underlying mechanism driving the better outcomes. However, some have expressed concern about the potential implications of the technology.

Nanny pill for psychosis: Undiscussed issue is effect on compliance broadly taken. Easy to imagine paranoid patient who takes pill reliably but feels spied on...& then fails to contact MD in face of subsequent episode https://t.co/KrBFFMh6ID

— Peter D. Kramer (@PeterDKramer) November 14, 2017

Noted bioethicist Arthur Caplan sounded the alarm on NBC News about the privacy implications of this technology back in 2015. (Several other experts also spoke to The New York Times about their concerns when the pill was approved this week.)

"The challenge to your privacy begins right now," he wrote, calling the device "snitch pills."

"How secure is the technology? Are hackers going to threaten to expose your medical secrets online if you don't pay, as they are doing in the Ashley Madison adultery hack? Will children or incompetent people be forced to use tracking pills with no consent, or will a judge have to authorize their use?"

Security and privacy "are extremely important issues," said Kabir Nath, Otsuka Pharmaceutical's chief executive officer in North America. "So we have done everything we can to ensure that this system, in its entirety, is compatible with the highest standards. That is a fundamental issue that we have addressed."

Other concerns have centered on the particular vulnerabilities of psychiatric patients, especially regarding access to the data that's collected. "This really is between the patient and the physician," Nath said. "Let me be very clear here: This system will only be used when this patient chooses with their treating physician to be treated with Abilify MYCITE."

"It is not going to be every patient with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder for whom this is an appropriate treatment," he said.

Thompson said the patient community was behind the push for this kind of technology. "The way that Otsuka discovered us is that patients themselves were putting up a booth at the National Association for the Mentally Ill, telling other patients about Proteus Technologies," he said.

Otsuka is planning to roll out the drug slowly, starting to offer it to people with a few insurance plans or with certain doctors. Then, it'll watch to see how things go and run studies.

"We are optimistic and ambitious that this can help to measure ingestion and ultimately, we might be able to demonstrate evidence around better outcomes for patients," Nath said.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kate Sheridan is a science writer. She's previously written for STAT, Hakai Magazine, the Montreal Gazette, and other digital and ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.