By the 1960s, there were only 15 giant Galapagos tortoises left on the isle of Española, in the southeastern Galapagos Islands. For the previous two centuries these tortoises were ravaged by whalers, who stopped by this rocky archipelago, nearly 600 miles west of Ecuador, and took the beasts aboard for food on long voyages.

It seemed likely that these animals would go the same way as a related subspecies, the Pinta island tortoise, whose final surviving member known as Lonesome George died in June 2012.

But in this tale of two tortoises, the Española story ends happily.

As recounted in a study published today in PLOS ONE, the 15 remaining tortoises were put into a special breeding program, and since the 1960s have produced more than 1,500 offspring, now living on the island and even beginning to breed in the wild. The population is now considered stable, says James Gibbs, study co-author and professor of conservation biology at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse.

"It looks like we are no longer needed," Gibbs tells Newsweek. "The tortoises can take care of themselves."

Gibbs has been tracking the tortoises and measuring the effectiveness of the reintroduction program since the early 1990s. The whole effort has involved hundreds of people over decades.

"The rebound of the Española tortoises from near-extinction is undoubtedly one of conservation's greatest success stories," says Dennis Hansen, a giant tortoise expert at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, who wasn't involved in the research.

The tortoises aren't just important because of their obvious human appeal, as large beasts that can live to 170 years old and move like shell-covered sloths. They are in fact "ecosystem engineers," helping to make life possible for a wide variety of other animals in this arid landscape, Gibbs says.

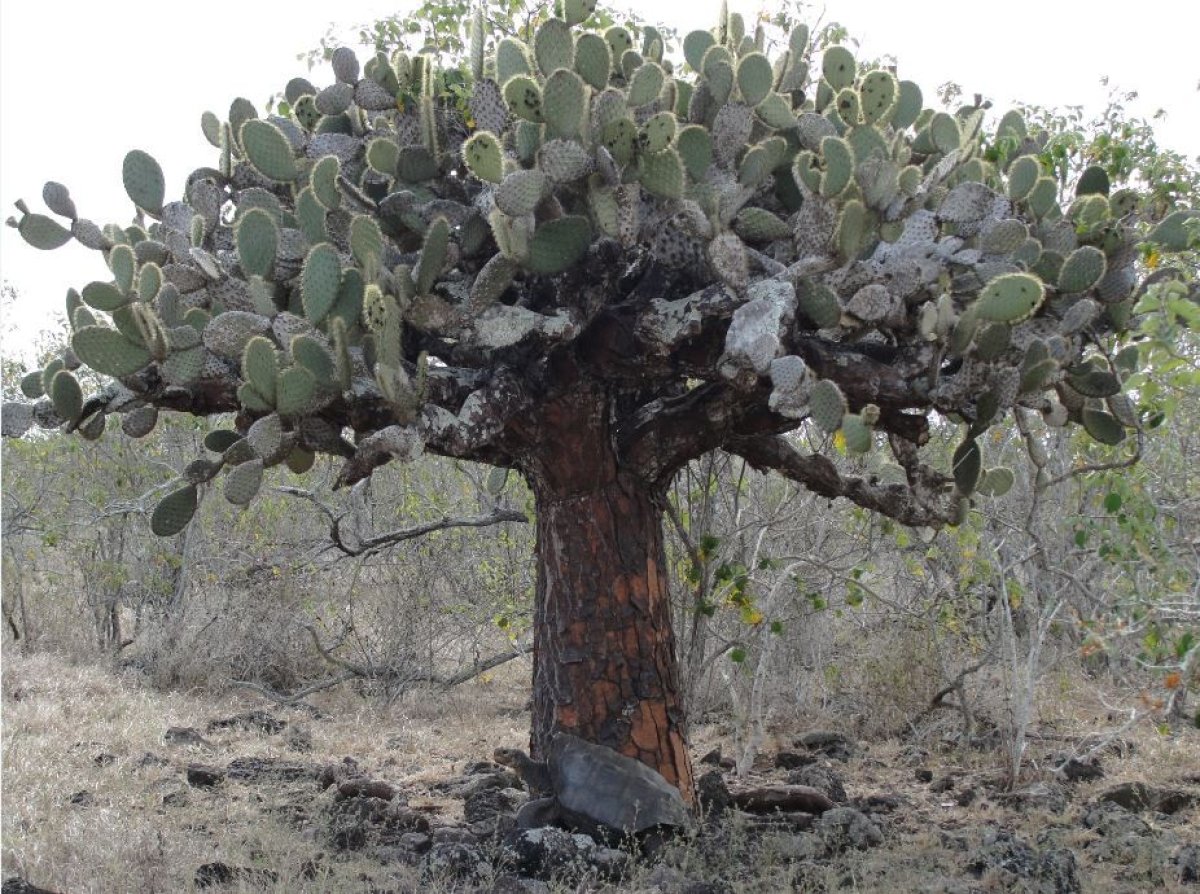

Primarily, the tortoises eat the fruits and pads of cacti, and disseminate the plants' seeds through their droppings, thus helping to spread the succulent plant throughout the island. Related subspecies of tortoises living on other islands do the same thing. Cacti, in turn, are a "keystone species" that provide food for songbirds, like finches and mockingbirds, and reptiles, like lava lizards, Gibbs adds.

Unfortunately, the Española ecosystem hasn't been in particularly great shape since goats were introduced about a century ago by fishermen to serve as meat on return voyages, Gibbs says. By eating everything in site, these horned intruders turned the island into a dust bowl. In the early 1970s every single last goat was killed by Galapagos National Park Service staff, but woody plants recolonized the land more quickly than grasses and cacti, and remain entrenched, Gibbs adds.

By trampling woody plants and spreading cacti, tortoises will shift the ecosystem back to its original pre-goat state, with more food-producing and water-efficient cacti and fewer woody plants, but it could take centuries, Gibbs notes.

"They more or less would garden their own ecosystem," says Hansen. "However, given the current dominance of woody plants, an initial human-assisted burst of selective felling and/or control of invasive plants to create more open areas might be a good idea."

Indeed, it's likely this possibility may be discussed by park staff and scientists next year, since the organization solicits advice from researchers for potential projects each year, Gibbs says.

Giant tortoises used to live in many places around the world but today only survive in the Galapagos and a group of islands east of Tanzania in the Indian Ocean known as the Aldabra Atoll. Some researchers are working on introducing the animals to other islands where they have been wiped out, for the animals' role as ecosystem engineers, Hansen says.

Today, Aldabra hosts more giant tortoises than the Galapagos, with a population over 100,000.

"And yet, Aldabra's giants were almost driven to extinction by overharvesting in the late 1870s, before Charles Darwin [and others] successfully appealed for their protection," Hansen says.

It all goes to show, Hansen adds, that tortoises are "very resilient critters if left alone."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Douglas Main is a journalist who lives in New York City and whose writing has appeared in the New York ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.