Less than 24 hours after the recent terror attacks in Paris, I caught a train in Amsterdam bound for the Binnenhof, the elaborate lakefront complex at The Hague and home of the Dutch Parliament. I was there for a hastily arranged meeting with Geert Wilders, a veteran member of the House of Representatives and Islam's arch-nemesis in Europe.

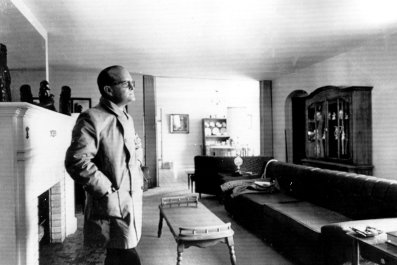

Security was tight that afternoon. Twice on the labyrinthian route to his office, I emptied my pockets, walked through metal detectors and watched as guards dug through my camera bag. Behind the key card-controlled door to his office, I was a little surprised to find Wilders, alone and standing behind his desk.

No fan of understatement, Wilders wore a shiny black Armani suit and a bright green tie. But it was his trademark platinum-blond pompadour that stood out, a haircut that many in the Netherlands compare to Donald Trump's rat's nest. Wilders may look just as cartoonish as The Donald. But unlike Trump, he's a legitimate force in politics. For nearly a decade, he's served as the leader of Holland's anti-Islamic political party, and he regularly uses his platform to denounce not only violent jihadists but all of Islam.

This stance has made Wilders a target for Muslim radicals. Death threats regularly arrive at his office, so seeing him sitting in a leather chair without armed guards, even behind so many checkpoints, is a bit unsettling. When I ask him how he's doing, he raises his eyebrows and answers: "Surviving."

It's an understandable response for a guy who has spent the better part of a decade wearing a bulletproof vest and being shuttled between safe houses to avoid assassination. "I'm not in prison," he says. "But I'm not free, either. You don't have to pity me, but I haven't had personal freedom now for 10 years. I can't set one foot out of my house or anywhere in the world without security."

Wilders's name is on the same Al-Qaeda hit list as Stéphane Charbonnier, an editor who was shot and killed during the jihadist assault onCharlie Hebdo, the French satirical magazine, that left 12 dead earlier this month. The massacre, along with the subsequent killings at a kosher supermarket in Paris, was a tragic day for the France. But for Wilders, it only added to his appeal. Since the attack, his Freedom Party has surged in national polls. It was already the most popular party in Holland, but if the 2016 parliamentary elections were held today, he'd pick up 31 seats out of 150, more than double his current figure.

If he found the right coalition partner, Wilders could even become Holland's prime minister, a once unthinkable prospect. Ten years ago, his proposal to ban the construction of new mosques in the Netherlands was mostly seen as the ravings of a fearmongering extremist who compares the Koran toMein Kampf. Now reporters call Wilders a "populist," and they no longer dismiss his xenophobic rants as rubbish.

His consolidation of power here isn't a foregone conclusion, but Wilders's growing popularity in Holland is emblematic of a larger trend: Europeans are becoming increasingly hostile to both native-born Muslims and the recent wave of immigrants flooding across their borders. Islamophobes are burning mosques in Sweden, marching by the tens of thousands in Germany and ceding more and more control to those politicians who speak the loudest against the Muslim faith.

Wilders insists he derives no pleasure from his newfound influence, but in the hours after the Charlie Hebdo shootings in Paris, he tweeted "This is war" to his 380,000 followers. By war, he tells me, he means a war with all of Islam. "The Islamification of our society is what's causing this," he said of the assault on Paris. "And it's all inspired by the Koran."

Wilders clearly knows that this is his moment, his chance to waggle his finger and proclaim "I told you so" to European politicians who haven't, in his view, taken the threat of terrorism seriously. As he puts it, "They refuse to define the elephant in the room, which is Islam."

DYED HAIR, DISGUISED ROOTS

Wilders will tell you that it's about the religion, not the people; that he hates Islam, not Muslims. But as he addressed a crowd in The Hague last March after a successful showing by his party in local elections, he got a little more personal. Flanked by two bodyguards, he walked to a small podium as "Eye of the Tiger" played on a cheap PA system, to scattered cheers. "I ask all of you," he said, waving his finger at the crowd, "do you want in this city, and in the Netherlands, more or less Moroccans?" His audience gleefully chanted, "Less! Less! Less!," to which Wilders replied with a smile, "Then we will arrange that."

The comments earned Wilders a comparison to Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister who in 1943 asked a crowd of Germans if they were ready for "total war." (Their response: "Yes! Yes!") Not long after Wilders addressed that crowd, a local prosecutor filed charges against him for hate speech. He faces a trial this year.

Wilders insists he did nothing wrong and said nothing new that day. His party's official platform implicitly advocates "less Moroccans" in the Netherlands by halting emigration from Islamic countries, promoting a voluntary exodus of Muslims (back to their native lands) and expelling Moroccans who commit crimes on Dutch soil. "Eighty percent of the Dutch jihadists who go to Syria are Moroccans," he says. (Other experts think the figure is slightly lower.) "We have an enormous problem with Moroccans; everybody has known this for 10 years."

This sort of racial rhetoric regularly earns Wilders comparisons to fascists, but he remains uncowed. "The biggest disease we have faced in the last decades in Europe is cultural relativism, the idea by liberals and leftist politicians that all cultures are equal. They are not," he told me. "Our culture, based on Christianity, humanism and Judaism, it's a better culture. We don't settle things with violence—well, sometimes we do, but mostly we don't. Cultural relativism has made it so people don't know who they are anymore."

And who is Wilders? Born in the southeastern Holland town of Venlo 100 miles from Amsterdam in 1963, he's the youngest of four children. He was raised Roman Catholic but has since left the Church and calls himself agnostic. The son of a printing company director, Wilders studied at the Netherlands's Open University and traveled extensively in Israel and throughout the Arab world during and after his compulsory military service in the Dutch Army.

At 17, he lived in the Jordan Valley, a few miles above Jericho, and while he was "a teenager, more interested in Israeli girls and beers," he decided that Islamic countries were dysfunctional and violent, and began to see Muslim immigrants as a destructive force in Europe. "I'm not against immigration because I believe all the people who immigrate are bad people," he says. "But they bring along a culture that is not ours. Islam is not there to integrate; it's there to dominate."

As Wilders grew older, he found new reasons to hate Islam. In the 1990s, he ventured into politics as a speechwriter for the center-right Dutch Liberal Party, under the tutelage of Frits Bolkestein, the party's leader and an outspoken opponent of mass immigration. Wilders was elected to the Utrecht City Council in 1997 and joined the parliament a year later. In Utrecht, he could afford to live only in the city's poorest—and majority-Muslim—neighborhood, Canal Islands.

He was an outspoken opponent of Islam then, too, and his neighbors knew it. After work each day, he says, he parked two blocks from his flat and walked home, hoping to avoid having his car vandalized. Often, he says, that walk turned into a frantic run, as Muslims recognized and chased after him. Once, in Utrecht's center, Muslim "street terrorists," he says, pepper-sprayed him, spit in his eyes and stole both his money and passport.

"I'm an elected politician," he says. "If you don't agree with me, vote for somebody else. What did I do, except for expressing my views?"

Despite what he told me about his time in Israel and Utrecht, some critics say Wilders's antipathy for Islam runs deeper. Dutch anthropologist Lizzy van Leeuwen has been researching the origins of Wilders's political philosophy since 2009, while working on a book about the colonial history of Holland. She discovered some material in the national archives and published an article later that year that revealed a secret Wilders had long kept hidden from the public eye: his Indonesian roots. Van Leeuwen is of similarly mixed blood, she said, and she was always bewildered at her mother's support of Wilders and his anti-Islam positions. At the close of the colonial era, Dutchmen were driven from the Indies by Muslims, many of them settling in places like the Netherlands, so when van Leeuwen discovered Wilders' Indonesian heritage, she grew curious.

"There's lots of bitterness among these old generations of colonial migrants," she says. "That's why Geert Wilders is a hero to them. He knows why people don't feel comfortable in this society of migrant groups."

Van Leeuwen's mother hides Wilders's books when her daughter comes now, but she is among many with an Indonesian background who admiringly call Wilders a "Branie," an Indonesian term for a man with chutzpah, with the balls to say what he thinks. "They were chased from their beautiful paradise in the sun," the researcher told me. "Now here's this guy saying it too, after everyone has been silent for 50 years, and he's their hero."

Van Leeuwen discovered that Wilders's grandfather was a high-ranking bureaucrat in the Dutch colony of Indonesia. Johan Ording, she says, went bankrupt several times in the Indies. He was fired while on holiday in Holland in 1934, warned not to return to the colony and later denied a pension. Mired in poverty, he and his family were forced back to the Netherlands in the middle of a harsh Dutch winter.

"You can call it cheap psychology to link these things, but I think this has meaning for somebody like Geert Wilders," Van Leeuwen says. "He is lost."

On some level, Van Leeuwen says, whether Wilders believes it or not, he's blaming Muslims for what happened to his family and seeking retribution. "He wants to go back to the way the borders were drawn before the war. Before decolonization," she says, referring to the period before Indonesia claimed its independence and was still a Dutch colony, called the Netherlands-Indies. "He once had serious plans to return parts of Belgium to 'Greater' Holland." He dyes his hair, she thinks, to disguise his Indonesian roots.

Wilders has responded to van Leeuwen's findings only once, in a television interview, saying her thoughts about him were "twisted," and he insists to me that he's not seeking revenge against anyone. But as he gestures emphatically from the safety of this fortified office a day after the tragic massacre in Paris, it's clear Wilders isn't the least bit mournful. He's fired up.

HOLLAND'S TEFLON DON

In November 2004, Dutch filmmaker Theo van Gogh was biking to work in central Amsterdam when a Dutch-born Moroccan named Mohammed Bouyeri attacked him, shooting him once and stabbing him several times. The filmmaker stumbled across the street, and Bouyeri followed, shooting and stabbing him again before slitting van Gogh's throat with a butcher knife, then lodging the knife in his chest with a letter attached to it. The attacker fled on foot, but was eventually arrested and sent to prison.

Van Gogh had been receiving death threats ever since he made an anti-Islam film called "Submission." But he wasn't the only enemy of Muslim extremists in Holland. His partner on the film, ethnic Somali lawmaker Ayaan Hirsi Ali, also received death threats, as did a rising politician she collaborated with on a letter in 2003 that called for a "liberal jihad" against Islamic radicalism: Wilders. A few months later, grenade-wielding attackers staged an hour-long siege of a building in The Hague, in an attempt to murder both Wilders and Ali.

Since then, Wilders and his Hungarian-born wife, a former diplomat to the Netherlands, have lived under constant guard, sheltered in a safe house with a panic room and driven to and from home in an armored police vehicle. When I met him at the Binnenhof, I couldn't tell if he was still wearing a bulletproof vest. But his office is strategically positioned deep in the parliament building so would-be attackers can approach it only from one corridor. Beyond that, Wilders wouldn't comment on what his security measures include. "That would make me only more vulnerable," he says. "Sometimes [the security is] more, sometimes it's less. Now it's certainly not less."

It's hard to know to what extent that attack affected Wilders's politics, but it clearly was a factor. From 2000 to 2006, he moved increasingly to the right, calling for a ban on head scarves in public and the sale of the Koran in general. A year later, he left his more mainstream party over its support for Turkish entry into the European Union and formed the Freedom Party, which surprised the country by winning nine of the 150 seats in the parliament.

"Try to imagine being attacked by a group of ideologically or religiously motivated people," says Meindert Fennema, a political scientist at the University of Amsterdam. "People tend to underestimate the fact that he is permanently under protection."

Wilders's rise has continued over the past nine years, and as he shored up political power, he also mastered the art of media manipulation. In 2008, he posted online a 17-minute film called Fitna, using excerpts from the Koran and statements of radical Muslims to paint a dark picture of Islam. The next year, the British government banned Wilders from visiting the United Kingdom to show his film, and prosecutors in Holland charged him with inciting hatred and discrimination (a Dutch court later dismissed the charges). Both the film and the ban generated headlines across the globe. In 2010, in perhaps his most well-known publicity stunt, Wilders visited Ground Zero in New York on the anniversary of the September 11 attacks, then spoke at a rally against the construction of an Islamic community center near the site.

"He's definitely playing the media," says Anno Bunnik, a Ph.D. fellow at Liverpool Hope University in the U.K., who specializes in politics, extremism and intelligence in the Middle East. "His positions are so polarizing…. Some say, 'Yes this guy is right,' and others say he's a total menace, and almost everything he says is automatically picked up."

'THE FIGHT WITH ISLAM HAS NO BORDERS'

For all the stunts, Wilders also owes his success to a nuanced, Tea-Party brand of Islamophobia. He's the first anti-Islam politician in Europe who doesn't come from an extreme right, nationalist background, says Fennema. He's liberal on issues like gay rights, which makes him appealing to a wider cross section of Europeans and helps him ally with a budding legion of politicians bashing Islam.

In recent years, politicians on both sides of the spectrum have employed Islamophobia as a rallying tactic. In France, Marine Le Pen's anti-immigrant Front National party is now the country's third largest. In Denmark, the Danish Folk Party works actively to prevent a "multi-ethnic society" by lobbying against immigration. Not unlike America's Tea Party and the Occupy Wall Street movement, this new breed of "populists" are critical of the political elite and believe government is no longer listening to the people. Experts say this combination of populism and nativism is a fruitful one because it provides a bogeyman for growing fears about globalization: the job-stealing, maybe even terroristic immigrant, and the established politician who shelters him.

In the past, Wilders tried to distance himself from Europe's nativist movement and instead focused his anger on Islam, says Matthijs Rooduijn, a political science professor at the University of Amsterdam. But in 2013, he decided to form an alliance with Le Pen in an attempt to cobble together a coalition to influence the European Parliament.

Wilder says he's convinced that if something isn't done to stop the spread of Islam across the West, our whole way of life will vanish and we'll all live in Muslim-ridden slums, assaulted for our Christianity and love of free speech. To make his case, Wilders regularly takes politicians from around the world on tours of majority-Muslim neighborhoods in the Netherlands, offering them a glimpse of their future if they don't beat back Islam.

Despite his antipathy toward Muslims, Wilders is clear that he doesn't advocate any kind of violence, and he insists he isn't responsible for attacks on peaceful and law-abiding followers of Islam. "If you set fire to a mosque, you're a criminal and I hope you go to jail for years," he says. "We should be tolerant to people who are tolerant to us. We should be intolerant to people who are intolerant to us."

How to stop the intolerance? Wilders has some ideas: immediately halt all emigration from Islamic countries, allow anyone who wants to leave the Netherlands to wage jihad overseas to leave, and pull out of the agreement with 25 other European countries that allows travelers to pass freely from one nation to the next. It's hard to say if these proposals are more likely to gain traction in the wake of the Charlie Hebdo attack. His party has performed well in opinion polls over the past 10 years, but that hasn't always translated to gains in the parliament. Even if his party does lock down the largest blocs of seats in the next election, he would have to convince another group to form a coalition in order to acquire any real sway. And because his views are so extreme, most political observers here find that unlikely.

"Other parties have said, 'We don't touch him, even if he is the biggest,'" Wilders acknowledges. "But I think anything is possible."

Not everyone is so sure Wilders will continue to have such a large audience. On the surface, the attacks in Paris may give him an easy chance to make a point, but van Leeuwen hopes that Wilders's grandstanding will backfire, that people will see it as a cheap attempt to seize power over the bodies of dead journalists. "There's a risk in talking the way he does in this moment," she says. "It's too obvious, too easy to declare all Muslims extremists and terrorists. Too many people will see through that. He has to be very careful."

In fact, many think his status in The Hague is increasingly secondary, that his bully pulpit may eclipse his day job. It's his notoriety, the attention he gets when he speaks out against Islam and immigrants, that could have a far greater impact on the ongoing debate about immigration here. That is perhaps why he seems so eager for his hate speech trial to begin; why he gave several interviews immediately after the Paris attacks; and why he's planning a trip to Australia, he says, to help right-wingers in that country start a political party modeled after the Freedom Party.

"The more famous he gets," Rooduijn says, "the less he needs to be a politician anymore."

Wilders is taking his message global. "This is not a national fight," he says. "The fight with Islam has no borders. The war has no borders. The fight for freedom has no borders."

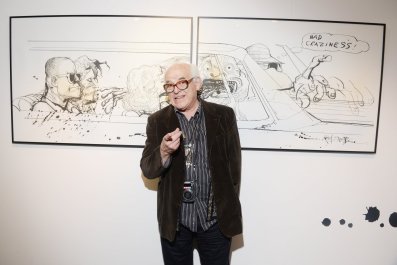

As Wilders escorts me out of his office, I notice the life-sized portrait of Winston Churchill hanging on the wall. Churchill is one of Wilders's idols, in no small part because of his criticism of Islam. Next to the painting is another figure Wilders clearly admires. It's a small, cartoonish sculpture enclosed in an acrylic case, a gift from some of his colleagues after a recent electoral victory. The sculpture is of himself.