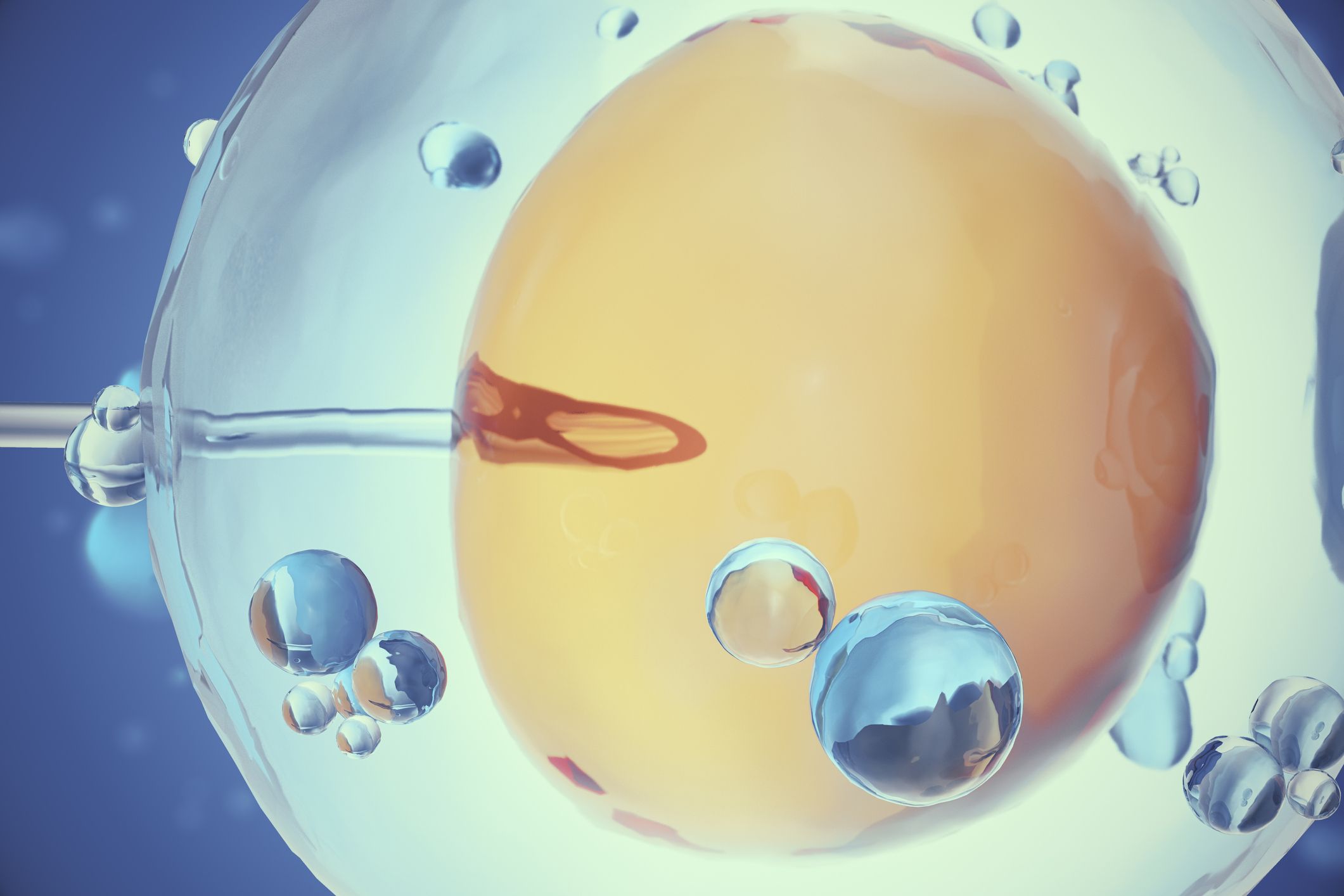

On Monday, the Associated Press reported a claim by a Chinese scientist, He Jiankui, that he had created the world's first genetically edited babies—two girls named Lulu and Nana.

While the claim has yet to be independently confirmed, the goal of the research was to provide the children with an increased ability to resist potential infections from HIV using an advanced technique known as CRISPR.

However, this kind of gene editing is banned in the United States, and if the claim turns out to be true, the scientific and ethical implications would be profound.

Below are the views of five experts on the matter:

Ainsley Newson, associate professor of bioethics at the University of Sydney

"While this research has yet to be subject to peer scrutiny—which in itself is problematic—it looks like the researcher involved wanted to be the first rather than waiting to be safe. It is still early days for human genome editing, with lots of scientific and ethical issues needing to be ironed out before it is used to change a genome of an embryo and its future descendants.

Susceptibility to HIV infection is not an obvious target for genome editing. We don't need genome editing to prevent HIV—we need to make existing preventive measures and treatments more widely available. Editing the DNA of healthy embryos to reduce the risk of contracting HIV is neither necessary nor appropriate.

This announcement also risks undermining the very careful research being undertaken globally to investigate the safety and future potential uses of genome editing to help avoid children being born with severe, life-limiting diseases.

If it is shown that these twin girls have indeed had their genomes edited, I hope that they are supported both medically and socially as they grow up, without becoming public curiosities."

Julian Savulescu, director of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, University of Oxford

"If true, this experiment is monstrous. The embryos were healthy. No known diseases. Gene editing itself is experimental and is still associated with off-target mutations, capable of causing genetic problems early and later in life, including the development of cancer.

This experiment exposes healthy normal children to risks of gene editing for no real necessary benefit. It contravenes decades on ethical consensus and guidelines on the protection of human participants in research. In many other places in the world, this would be illegal and punishable by imprisonment.

Could gene editing ever be ethical? If the science progressed in the future and off-target mutations reduced to acceptable and accurately measurable levels, it might be reasonable to consider first-in-human trials—with appropriate safeguards and a thorough ethics review—in one category of embryos: those with otherwise lethal catastrophic genetic mutations, who are certain to die. Gene editing for this group might be lifesaving; for these current babies, it is only life-risking.

These healthy babies are being used as genetic guinea pigs. This is genetic Russian roulette."

Hannah Brown, expert in reproductive biology and chief science storyteller at the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute

"While completely unsubstantiated, the reports today of the birth of the first genome-edited babies are hugely alarming.

Points of major concern in the report include:

- The conflict of interest of the "researchers" who own companies/have a financial interest in the success of the technology.

- The report that the lab didn't know they were dealing with patient samples that were HIV-positive (reported to protect the status of the patients involved).

- The reports that the "researchers" involved have no experience running clinical trials and who are trained in physical sciences.

- The report that the patients may not have been appropriately briefed on the experimental nature of the trials.

- The report that an embryo with a known failure in the editing process was transferred, suggesting that they were actually interested in testing the safety/efficacy of the technology and not the genetic resistance to HIV for the patients/babies.

The implications for cowboy-style "researchers" taking experiments into their own hands risk damaging the already fragile relationship between science and society."

Channa Jayasena, clinical senior lecturer in reproductive endocrinology, Imperial College London

"It was always inevitable that genetic modification of humans would begin. My fear is that this has been rushed through without due consideration of the consequences, both for human health and for society. Making mistakes during gene editing may create new genetic diseases, despite the noble intention of preventing genetic disease by cutting out the 'bad DNA.' Will this open the door for 'designer babies' who have been selected for specific physical and behavioral traits? We urgently need an international treaty to regulate gene editing of humans, so that we can decide if and when it is safe to use."

Darren Saunders, gene technology and cancer specialist in the School of Medical Sciences at the University of New South Wales

"Scientists everywhere today will be thinking "show me the evidence," and some of the claims from the scientists involved suggest that the gene editing was only partially successful. If confirmed, this represents a huge technological and ethical leap. It's possible we just saw a huge leap towards editing the human book of life—some might even suggest this is a step toward eugenics.

Even seeing the detailed data may be tricky. No reputable scientific journal should touch this story if the experiment was done without the appropriate ethical approval—as seems likely from comments attributed to the scientists involved. This aspect of the story is really problematic and disturbing. Experiments like this risk setting back the entire field. Science operates under a social license—scientists work within limits defined by broader community concerns. Ignoring those boundaries risks a justified backlash and fear that can set back the entire field by decades."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.