In 1974, Clive Davis was already a legend in the music business. The son of a tie salesman from Brooklyn, the sharp-dressed executive had been a lawyer for 10 years before being picked to run Columbia Records in 1967. He had an unerring eye for talent, signing a string of future stars, such as Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, Chicago, Pink Floyd, and Santana, and doubling the label's market share in three years.

Davis was gregarious, always in a suit and tie, and he liked to get involved in the production process. He often went to nightclubs in New York and Los Angeles to check out the latest music. He was familiar with Gil Scott-Heron's Pieces of a Man album and had been impressed by "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" when he first heard it on the radio in 1970. "To me, it was obvious that he was someone with a new voice, a fresh take on things, coupled with the shimmering rage of the Nixon years and how he and Brian fused funk and jazz and spoken word." Still, Gil's band was too underground for him and his pop sensibilities.

It was the summer of 1974 when Davis heard "The Bottle" playing on radios all over New York City and realized Gil's appeal could be much broader. He was starting his own label, Arista, looking for new talent to sign, and he wanted to check out Gil in concert, so he and Stevie Wonder went to go see Gil and the Midnight Band perform at New York's Beacon Theater. "I remember it vividly and I remember being floored," says Davis. "He was such a charismatic, compelling, striking young artist, very much of his moment in time. I was very taken with him." He compares it to the first time he saw Patti Smith and Whitney Houston perform. "This was someone whose impact would be profound."

Davis went backstage and met Gil, and then they met again in Davis's office, where they traded stories and established a warm bond. The partnership was unique: an established music industry giant taking a chance on a politically controversial spoken-word black poet with militant leanings.

Davis had big plans for Gil, envisioning him as the voice of his generation, with the potential to top the charts. Soon after signing him, he took Gil to see Elton John at Madison Square Garden. "I think he was trying to show me what he saw me doing without making that speech."

They called that first Arista album The First Minute of a New Day, to mark the new chapter in Gil's career and Davis's new company. Gil and Brian Jackson quickly assembled some of the old gang that had created the first albums. Victor Brown had been back in Boston, teaching classes and enjoying his apartment in the South End when he got a call from Gil to come to DC. "I'm putting a band together—how soon can you get here?" Victor was in New York the next weekend, reuniting with buddies Ade Knowles and Danny Bowens and meeting a few new faces, including fiery saxophonist Bilal Sunni-Ali, who was a member of the Black Panthers.

The politics of the album reflected Gil's growing awareness of global issues and his interest in Afrocentrism. The most uplifting song is "The Liberation Song (Red, Black and Green)," which refers to the colors of the pan-African flag, a symbol of liberation:

I've seen the red sun in the autumn

And I've seen the leaves turn to golden brown

I've seen the red sun in the autumn

And I've seen the leaves returning to golden brown

I've seen the red blood of my people

Heard them calling for freedom everywhere

The album evoked the inspirational mood of the civil rights movement on "Must Be Something" and "Western Sunrise," but it also reflected the harsh reality that the dream of Martin Luther King Jr. had turned dreary 10 years on. Just as in Winter in America, the tone was mournful, with Gil decrying the growing apathy and self-absorption of young Americans, including young black Americans: "What ever happened to the protest and the rage?"

Using the previous album's title as a new song for this album, Gill had scribbled the lyrics to "Winter in America" in a notebook over a few days—and it remains one of his most memorable works, poignantly evoking a low point in American history and the faded dreams of the 1960s. He painted a dismal history, from the mistreatment of native Americans and the near-extinction of the buffalo, to overdevelopment, "the forests buried beneath the highways," and environmental catastrophe. Somberly, he concludes: "It's winter, winter in America / And ain't nobody fighting because nobody knows / What to save."

Though Davis wanted to feature Gil's profile on the album cover, Gil didn't like having his picture taken and pushed to use an image of a gorilla, playing off the fact that it was a homonym for "Guerilla," one of the album's tracks. The ape sits in a wicker chair, mimicking an infamous photo of Black Panther Huey Newton. Years later, Gil explained his choice by saying that gorillas are peaceful creatures until they're provoked into violence. "They're only hostile when attacked. But when attacked, they're extremely hostile," he said with a laugh. "That's where we're coming from."

Their original idea for the album cover type prominently featured "The Midnight Band," with Gil and Brian's names in much smaller type, down in the lower right-hand corner. "That bothered me," says Davis. "After seeing them in person, I thought that the spotlight should be on Gil." He compares his choice to how he pushed then-unknown rock group Big Brother and the Holding Company to highlight Janis Joplin on the album cover and in their promotional efforts, which led to massive record sales.

"I never meant any disrespect to the contributions of Brian and the other players, but to me, the star was Gil," says Davis. He felt that Gil could have an enormous impact on society through his powerful lyrics and public statements, and branded him the "black Bob Dylan," encouraging his promotional executives to use that term in their publicity material. Gil didn't appreciate the comparison. He felt that the work stood on its own. "Clive said that so people could relate to what we did," Gil later explained. "But he never said that to me. As far as I knew, Dylan played harmonica and I played piano, Dylan couldn't sing and I could, that made a difference right there."

When journalists made the comparison in interviews, Gil replied with anger or amusement, depending on his mood. When Playboy's Vernon Gibbs brought it up in an interview in 1976, Gil told him it was an insult, giving him a "deadly glare" and snorting "contemptuously" before spitting: "I'm doing something else altogether and I would guess that anyone with an adequate amount of perception would be able to dig that." His anger seemed more calculated than genuine, fueled less by resentment of Dylan than out of frustration with the media's lazy comparison. "No, I'm not into him, man." (Gil neglected to mention his own soulful rendition of "Blowin' in the Wind" to an auditorium of students back when he was in high school.) When Gibbs pressed, insisting that Dylan had taken up the mantle from Woody Guthrie and helped start the protest movement, Gil shot back, "Man, we got protest songs that go all the way back to the 1700s." And he explained for the umpteenth time that he didn't consider himself a protest singer and that he was tired of fans showing up at performances expecting "to see some wild-haired, wild-eyed motherfucker… ."

Released in January 1975, the heavily promoted The First Minute of a New Day earned near-universal praise. In its review, Rolling Stones said "the eloquent literacy of his melodic songs speak with extraordinary insight, anger and tenderness of the human condition." The Washington Star-News called it "Black music of the future," and the Los Angeles Herald Examiner described the album as "an angry sound and a celebratory sound, tinged with Latin street rhythm and pulsing with the urgent beat of his African heritage."

With Arista's marketing and promotion muscle, album sales soared over the next few months. Clive Davis was thrilled, calling the reaction "unusually strong, defying any conventional categorization, as we continue to see enthusiastic response at progressive music, rhythm and blues, and FM levels." But lacking a hit single, the album didn't do quite as well as Winter in America, which had been propelled by the success of "The Bottle." Still, the album made it to No. 5 on the jazz charts and No. 10 on the R&B charts, numbers that Davis can still recite from memory.

Davis often brought his friends in the music business to see Gil perform. In a photograph taken after Gil's debut performance as an Arista artist at New York's Bottom Line in February 1975, the music impresario confidently looks at the camera with a cocky grin as he stands between Gil, young and intense, and Stevie Wonder, smiling ecstatically in his black sunglasses. "Stevie admired Gil so much," says Davis. After the show, Wonder told Newsweek's Maureen Orth, "Gil says things a lot of people are afraid to say." The writer was impressed, praising Gil's ability to enlighten and entertain during an era when "mindlessness and recycled rockers dominate the hit charts." But the band was also self-aware enough to know that there was a flipside to that adulation from the sophisticates in Manhattan and the black intelligentsia in D.C. "We were radical chic," says Brian Jackson. "A lot of people came to our shows because they wanted to be seen coming to our shows. We were too hip for words."

A few band members who rejoined Gil on The First Minute of a New Day were hardly prepared for how things had changed now that the band was on a major label. Instead of playing in front of hundreds of students in an auditorium at colleges like the University of Connecticut in Stonington, they were opening for Earth, Wind and Fire at the Roxy, before an audience of thousands, and performing at Carnegie Hall. The band had gone from gigging every other month to being away on the road for almost six months a year. Brown remembers his first big show, playing at the Cole Field House basketball arena in Columbia Point, Maryland. "There was a huge screen where I could see myself as I was performing—I couldn't look at that and be able to perform. I had to close my eyes!"

Victor Brown remembers playing with Taj Mahal at the Hollywood Bowl; for the giant finale, the two bands joined forces for a 25-minute percussion jam. "I can't imagine what that does for an audience. Even our roadie came up onstage with a cowbell." Gil's charisma won over legions of new fans, who would roar with enthusiasm when he hit his rhetorical highlights and punch lines. Once lashing out at President Ford's recent pardon of Richard Nixon, who got to keep his pension, Gil thundered, "Do not pass go, go directly to jail, do not collect 200,000 dollars."

Davis's business smarts and connections in the music world—the label signed Barry Manilow, Dionne Warwick, and Melissa Manchester— propelled Arista within a year to one of the top record labels in the world. To celebrate, Davis, ever the showman, threw a giant party at Madison Square Garden, with Gil and the band playing in the afternoon with other jazz artists, such as Anthony Braxton. When singer Eric Carmen's bus overturned on the New Jersey Turnpike, Davis asked Gil and his band to fill in that slot as well. The band was exhausted but marched back onstage to run through their repertoire, including "The Bottle." The venue, enormous for a band used to playing jazz clubs and smaller auditoriums, had a special significance for Gil. The last time he'd set foot on that legendary floor, he was playing high-school basketball for Fieldston against conference rival Collegiate.

During the gig, the applause and crowd chatter were so loud he sometimes had trouble hearing the other members of his band. But that didn't bother Gil. He paced the stage, clutching the microphone and flashing a huge grin. Not all the critics were impressed with Clive Davis's black Dylan—Gil's singing and demeanor were "limited and self-satisfied," wrote the New York Times's John Rockwell, who otherwise praised the band's percussion-fueled energy. None of that could dampen Gil's mood. He told friends in the following days that the show was the highlight of his career, the moment when he knew he'd arrived.

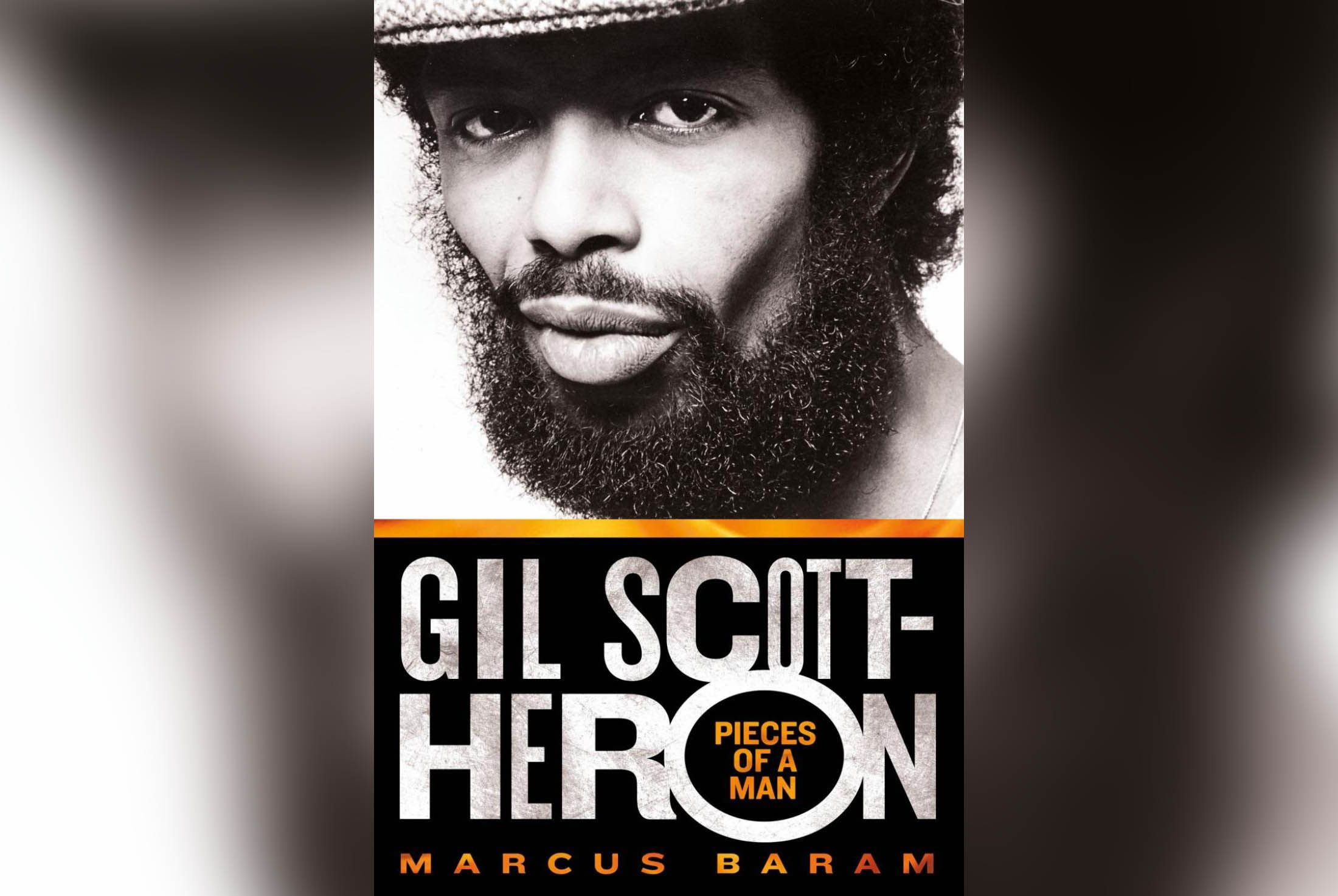

This excerpt is from Gil Scott-Heron: Pieces of a Man by Marcus Baram, published by St. Martin's Press. Copyright © 2014 by Marcus Baram. Reprinted with permission of the author. All rights reserved.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.