A 100-foot-long hidden chamber has been discovered in the Great Pyramid of Giza. The huge void was used by scientists using cosmic rays—particles from space that allow them to build up a 3D picture of the internal structure of the Great Pyramid without actually going inside it.

What is the Great Pyramid at Giza?

The Great Pyramid is the largest of three pyramids in the Giza complex—probably the most recognizable feature of the ancient Egyptian civilization. It was built between 2580 and 2560 BC, having been commissioned by King Khufu, one of the most powerful pharaohs from the fourth dynasty.

It is thought to have taken 20 years and tens of thousands of skilled builders to construct the monument. The Giza complex also houses workers' camps and cemeteries, indicating they were paid laborers rather than slave laborers, as the Ancient Greeks believed.

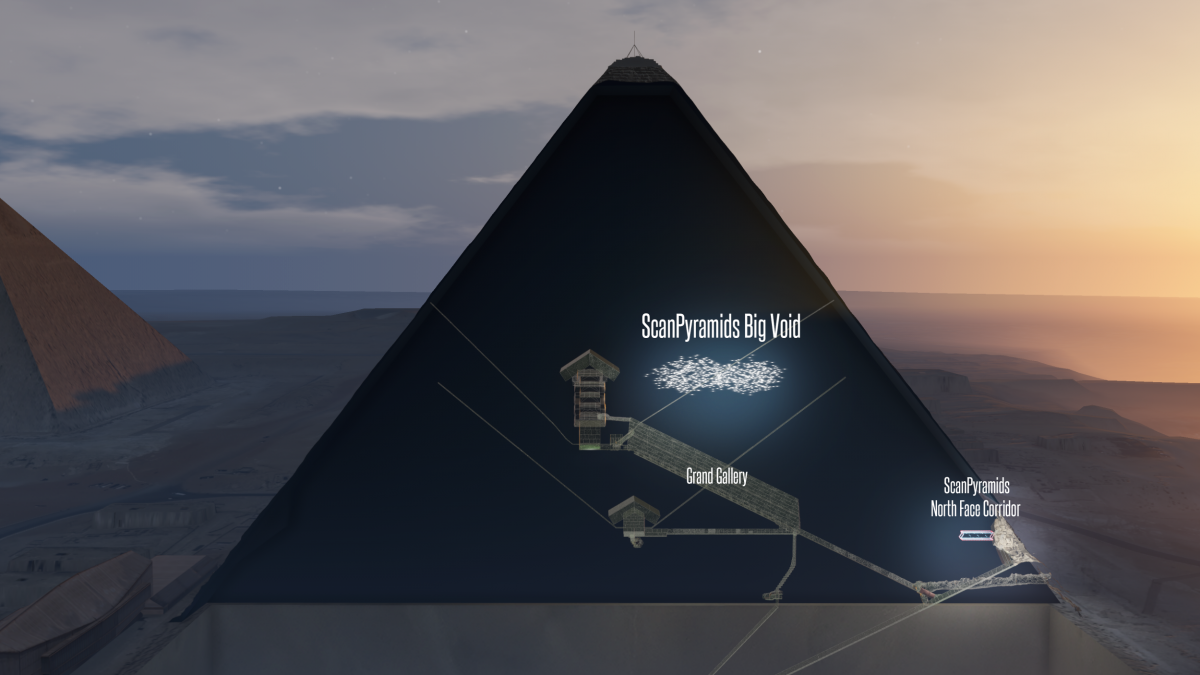

The pyramid contains three main chambers—the Queen's Chamber, the King's Chamber and a subterranean chamber. It also has a Grand Gallery—a 153-foot-long corridor with a steep incline that connects it the other rooms.

What is the new chamber?

The newly-discovered chamber, findings of which were announced in the journal Nature, is a 100 foot-long, 26-foot-high void that sits directly above the Grand Gallery, with a very a similar cross section, indicating that the two are connected in some way.

Scientists do not know what is inside the void—just that it is there.

This means it could be a new room full of treasure, or it could be something that was included in the design of the building for architectural purposes. Kate Spence, Senior Lecturer in Egyptian Archaeology at the University of Cambridge, U.K., believes the latter is the more likely explanation.

"What they seem to have found is a linear anomaly above a gallery which is a very complex piece of construction in the center of the Great Pyramid," she told Newsweek. "If you look at the cross section of the pyramid, above the kings chamber—the main burial chamber—there are a whole series of little chambers which are roofed with incredibly heavy big granite blocks. My suspicion is what they are looking at is the remains of a constructional ramp which has been built within the pyramid probably for getting those blocks into place."

How was it found?

The ScanPyramids project was launched in October 2015 under the authority of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities. It is led by the HIP Institute and Cairo University as a scientific mission to non-invasively produce scans of Egypt's pyramids.

To do this, the team uses cosmic rays. Earth is bombarded by particles from space every day. These particles—muons—can pass through dense objects like stone, but when they move into a space that is less dense, their trajectory changes slightly. By tracking muons, scientists can trace these changes to build up a 3D picture of the internal structure of a given building—in this case, the Great Pyramid at Giza.

"The known voids (King's chamber and Grand Gallery) are observed as well as an unexpected big void, which fully demonstrates the ability of cosmic-ray muon radiography to image structures," the team wrote in the paper.

Will the chamber be explored?

The ScanPyramids team said more research needs to be done to understand the internal structure of the monument. They said that while their findings confirm the existence of a hidden void, there are many more things to consider—the space could be made from one or several adjacent structures, and it could be inclined or horizontal. The team is calling for more interdisciplinary collaborations to better understand what they have found—and how this potentially relates the construction process of the pyramid.

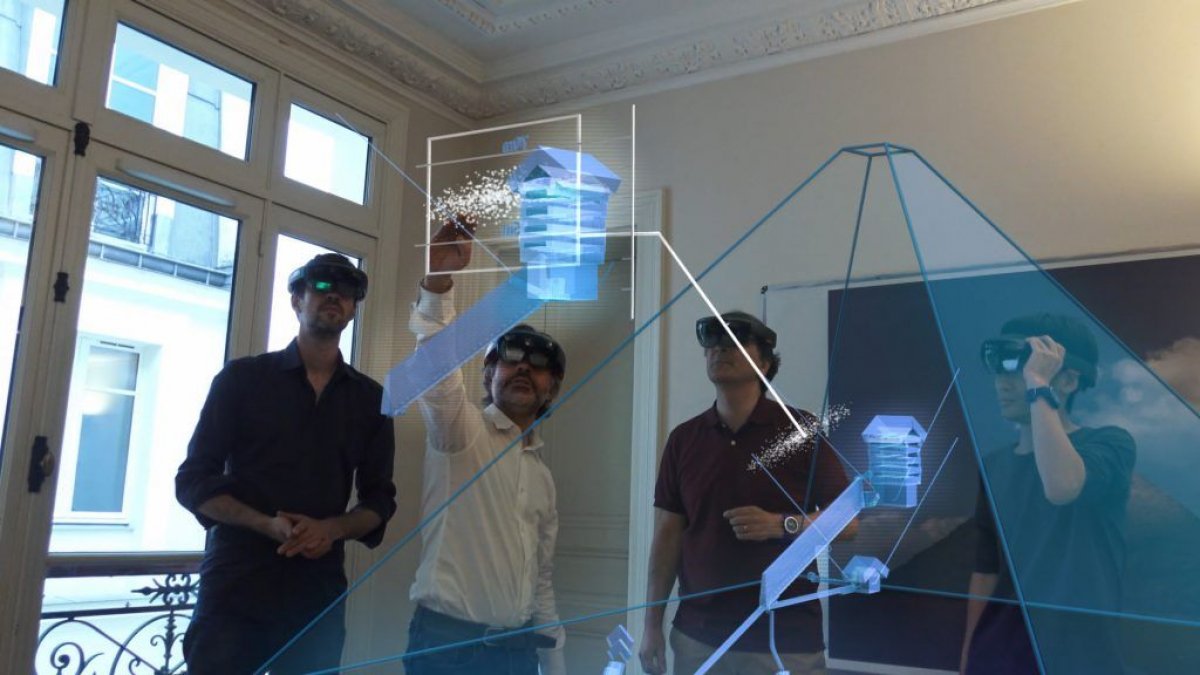

In a press conference about the discovery, the team said that physical exploration was a possibility, but that would be up to the relevant authorities to decide. Accessing the chamber would require significant drilling at the site, causing damage to the pyramid. The team said technologies currently being developed could make exploration as non-invasive as possible. They say one option could be drilling a very small hole and using a tiny flying robot to explore the chamber.

Spence said exploration with the least invasive techniques is preferable: "I would think it would be a pity to try to go into it because they would have to drill an awful long way, it would damage the monument and they might not be able to say an awful lot about it. [But scientists are] coming up with such exciting methods of imaging now that they can collect more info in those ways non-invasively. That's really exciting when you can get info without having to damage monument in the process."

How was Giza's Great Pyramid built?

This is one of the biggest archaeological mysteries of all time. As the scientists note in the Nature paper, our understanding of the Great Pyramid mostly comes from architectural surveys and comparative studies with other pyramids.

"One of the problems we have with the great pyramid is there are no direct parallels for the internal structure of it," Spence, who was not involved in the study, said. "It's quite unusual, and when it's unusual and nobody has written anything down about it, it can be very difficult to interpret what's going on."

The only known document that references the pyramid's construction were discovered in 2013, but they only described the logistics of the building work—like how the huge stones used were transported to the site—rather than the architectural planning.

If the newly discovered void was an integral part of the construction process, it should give us a far better understanding of how the ancient Egyptians planned and built this huge structure.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Hannah Osborne is Nesweek's Science Editor, based in London, UK. Hannah joined Newsweek in 2017 from IBTimes UK. She is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.