From the Middle East to the heart of Europe, countries are struggling to deal with a massive surge of desperate people crossing their borders, some fleeing for their lives, others escaping poverty and in search of jobs.

The number of people forced to flee their homes is staggering. According to the United Nations refugee agency (UNHCR), there are 65.3 million people forcibly displaced, including 21.3 million registered refugees who have fled their home countries to escape conflict or persecution. "In addition to the refugees, there are 244 million international migrants—probably an underestimate—and if you add to them the 750 million domestic migrants, you have 1 billion people; that is 1 billion in our 7 billion world," says William Lacy Swing, director general of the International Organization of Migration (IOM). "One out of every seven people on the planet is in a migratory status."

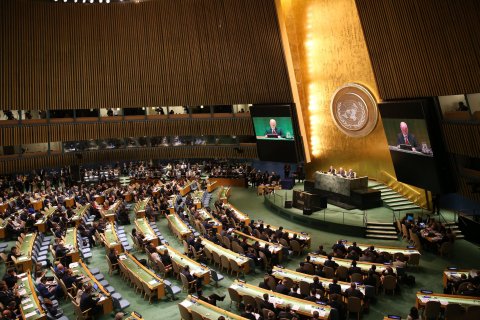

The U.N. and the United States convened two international summits in September to deal with what Swing calls the "mega-trend in the 21st century…more people on the move than at any other time in recorded history."

While the U.N.'s record on resolving conflicts has not been impressive in recent years (think Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, South Sudan and more), it has generally been an important force in taking care of refugees—a task shared by agencies including the UNHCR, the children's nonprofit UNICEF and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs.

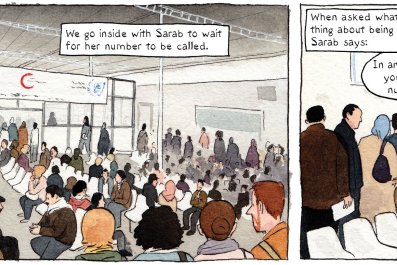

But from the beaches of Lesbos to refugee camps in Kenya, Turkey and Jordan, the U.N. agencies are now overwhelmed. At the same time, there is a backlash against the newcomers in the United States and Europe, the latter of which in the midst of an economic downturn has found its basic services severely taxed.

Immigration and refugees have been a major issue in the U.S. presidential election, with Republican candidate Donald Trump vowing to build a wall along the southern border with Mexico to stop immigrants from entering the country illegally and to deny entry to Syrian refugees and other Muslims. "The migration narrative right now is highly toxic," says Swing. "It is the cruel irony that people fleeing terror are then accused of being terrorists themselves."

Convincing 193 nations to agree on how best to handle the twin problems of migrants and refugees was not easy—while refugees already have legal protection and rights under international conventions, there is no such consensus on economic migrants, and many richer countries are resistant to changing that.

The key negotiators of the U.N.'s New York Declaration on Migrants and Refugees were Jordanian Ambassador Dina Kawar—concerned with millions of refugees pouring into Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Africa—and Irish Ambassador David Donoghue, whose primary focus is the influx of people to the European Union.

Donoghue concedes there was less commitment in the final U.N. agreement than he had hoped. "Inevitably, in a negotiation like this, among 193 member states, you're not going to be able to stay at the high point of moral fervor," he says. "You're going to have to acknowledge that some member states have concerns, and it got diluted a little bit."

Among the main breakthroughs, the negotiators say, was that they brought migrants, not just refugees, into the U.N.'s purview.

The 22-page outcome document, which forms the basis for this new agreement, is composed of 12 pages plus two annexes—one for refugees and one for migrants—and sets out a two-year timetable to negotiate specific actions. "Negotiations would begin in early 2017 and would run up until an intergovernmental conference in 2018," Donoghue says, "but we've already done a fair amount of the groundwork for that global compact on migration because the annex we're talking about sets out a number of key elements."

Among those elements: programs for countries to absorb migrants and protections for them; provisions to educate migrant children; and burden sharing of existing migrant populations. What's more, the document makes a case that migrants can have a positive effect on society.

That language was resisted by some countries, Donoghue says (he declined to say which), but others were determined to include it. "Let me put it this way: The champions of migration in the broader sense, over many years at the U.N., have included Bangladesh, Mexico, Sweden and a number of others.

"Migration up till now has never been addressed at the U.N. because it was seen as an issue for national sovereignty," he adds.

The agreement also focuses attention on refugees and reminds nations that they cannot, under international law, send people back to a country if they fear persecution and stresses that refugees should be given work and their children educated. It also urges countries to take back nationals if they do not meet the requirements of asylum.

Another contentious issue was how to handle internally displaced persons. "IDPs deal with sovereignty," says Leonard Doyle, spokesman for the IOM, "a very tough nut to crack when dealing with the U.N. system because, by definition, they happen within a nation's territory."

The attitude from some countries' representatives, he s ays, was the equivalent of "Don't even think about parking in that spot," so the document simply noted that other development goals of the U.N. recognize the need to care for IDPs and mentioned the need for "reflection" in order to protect IDPs and prevent the root causes of the problem.

Which countries changed what during the negotiations reflects the deep divides on the subject. Kawar and Donoghue say the discussions were intense: Every single word was debated, and some things were just off-limits.

When the negotiations began, there were plans to have concrete proposals to resettle refugees and share the burden of new ones around the globe, since 86 percent of refugees are in the developing world. Many migration and refugee advocates wanted specific pledges to resettle one-tenth of refugees, but that met resistance from several countries, including Russia. The final agreement simply has a vague commitment to "cooperation."

Human rights language was also watered down. "You're always going to have a tension in a negotiation like that between the global north, which has a strong view of human rights," Donoghue says, and countries that have issues with human rights abuses.

The U.S. wasn't very pleased, the organizers say, that some of the commitments would be diluted and at first planned a summit on refugees on the same day as the U.N. summit. After much back and forth, the U.S. moved the date of its meeting back a day, so that the conferences complemented each other. The U.S. would bring together countries that agreed in advance to make a contribution to one of the areas of reform.

The U.S.-led Leaders' Summit on Refugees was co-hosted by Canada, Ethiopia, Germany, Jordan, Mexico, Sweden and the United States. According to the White House, 52 countries and international organizations attended and pledged to increase their current financial contributions to U.N. appeals and international humanitarian organizations by $4.5 billion over the past year, double the number of refugees they resettle or admit legally in 2016 to 360,000, improve access to education for 1 million refugee children globally and give legal aid to 1 million refugees globally.

The fate of children was a particular concern at the two summits, and while the United States likes to be seen as a leader on refugee issues, human rights groups criticized the country over its position in one area: the detention of child migrants, many of them unaccompanied children fleeing violence in Central America.

An early draft of the U.N. document said detention of minors, either because they're unaccompanied or based on their parents' migration status, is never in the best interests of the children. That was changed to seldom by the U.S., to the chagrin of 35 nongovernmental organizations, including Oxfam America, Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International USA.

"The starting point," says Wendy Young, executive director of Kids in Need of Defense, "is that detention is not in the best interests of children."

Young, who co-hosted a "shadow summit" on children on the sidelines of the U.N. summit, says the U.S. has made some progress in handling children, but it still considers those coming from Central America as migrants rather than refugees, and it needs to acknowledge that "the violence in Central America is generating a forcible displacement situation." While she praises President Barack Obama for calling the refugee summit, she says: "While you are talking the talk, you also have to walk the walk."

"We have a refugee crisis happening on our own back doorstep," she says, and the U.S. has been responding with "mixed signals."