Even in the baddest bad-ass behavior of his basketball days, when his hair looked like flame and his enormous piercings seemed made from a chain-link fence and it was always hard to divide his reality from his calculated ridiculous, it was inconceivable that Dennis Rodman would one day change world diplomacy.

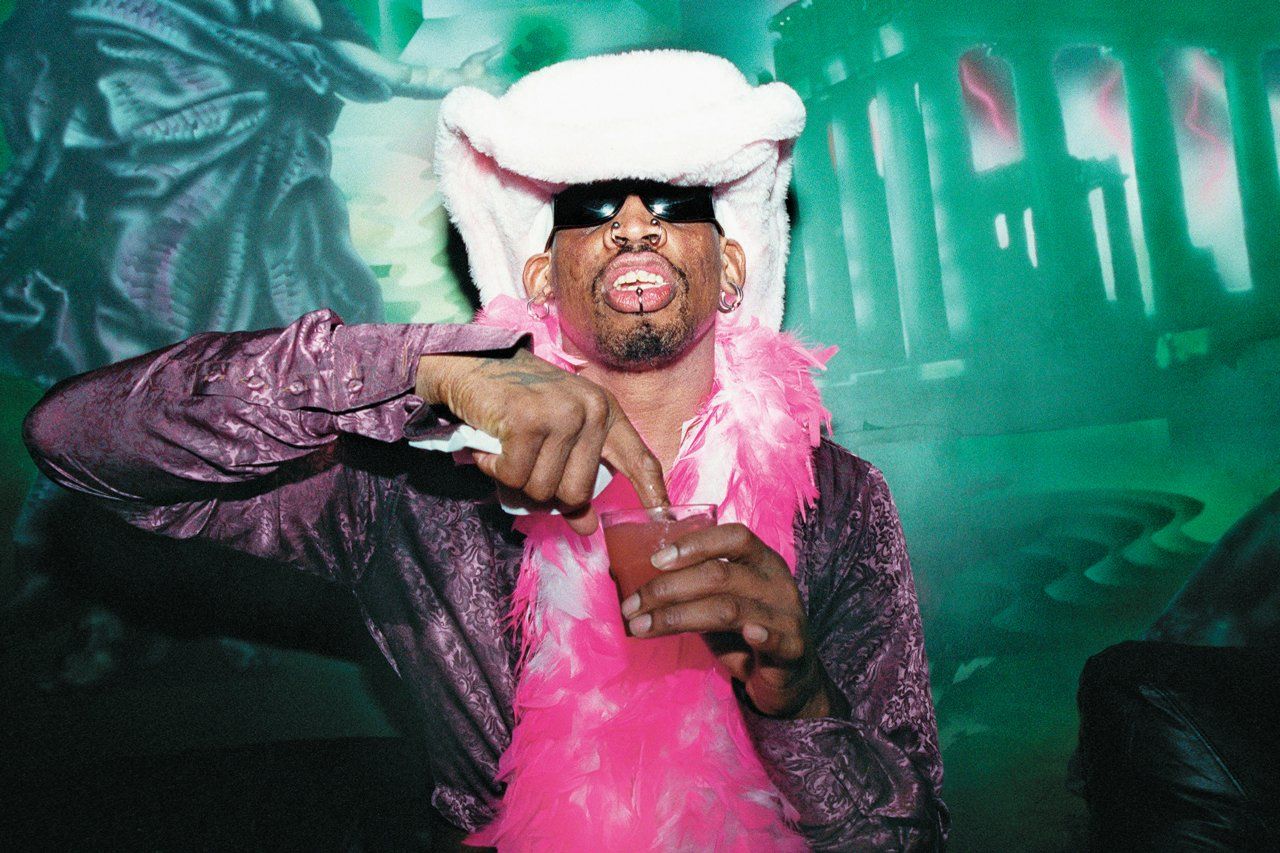

Hip-checking the Utah Jazz's John Stockton and pushing the Chicago Bulls' Scottie Pippen into the stands when he played in the National Basketball Association? Yes. Head-butting an official? Yes. Kicking a cameraman in the groin? Yes. Wearing a bridal gown to promote his book, Bad as I Wanna Be, that sold a million copies? Yes. A sartorial style that was a mix of Liberace and Phyllis Diller and Dudley Do-Right? Yes. The undeniable kinkiness of sex with Madonna as well as the apocalyptic nightmare of it? Yes. Arguably the best rebounder in the NBA over the past 40 years with an uncanny gift and instinct for the game? Yes. Vulnerability behind the feathery boas and the Wizard of Odd costumes? Yes. Abandonment issues? Yes. A craving for attention? Yes. Wincing candor? Yes. Naiveté. Yes. Alcoholism? Yes. Complexity? Yes, yes, and yes.

But creating the tempest that no athlete in modern times has created by yukking it up several weeks ago with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un despite a record on human rights that is likely the worst of any country in the world? No.

Not even Dennis Rodman seemed remotely capable of such accomplishment.

But idiosyncratic individuality, even in the blur of globalization and homogenization, still has a place. You may hate Rodman for later calling Kim a "good guy." You may get up on your high horse and compare him to Charles Lindbergh when he appeared with Hitler in the 1930s. But hey, where the hell were we? Sitting in our mancaves and womancaves in the United States watching Dennis Rodman in North Korea.

For a man who had slid into the ozone layer of virtual obscurity after a controversial and colorful 14-year career in which he won five championships with the Detroit Pistons and the Chicago Bills, and who is reportedly broke despite the tens of millions he once made in salary and endorsements, this may have been the smartest thing he has ever done, whether he knew it or not.

He did not initiate the trip, accompanied by three members of the Harlem Globetrotters. It was orchestrated by a Brooklyn company called Vice Media as part of a new newsmagazine show on HBO, also called Vice. It seemed clear Rodman knew absolutely nothing about the appalling human-rights record of North Korea.

At least he took a stand, even though it was a horrible one, unlike virtually every other fellow athlete, where political boldness has become pointing a finger at the sky after a touchdown or home run or three-pointer, Praise Be to God as if God gives a toss.

As noted by Esquire writer-at-large Scott Raab, who got to know Rodman well in the 1990s and once got tattoos with him, he did engage with a country and a leader in which hundreds of journalists and politicians and business big feet have tried and failed. Rodman and the Vice film crew became the first known Americans to meet Kim since he inherited power from his father.

It was completely mondo bizarro. Of course it was mondo bizarro. Maybe it was ill advised. But the trouble with life today is that not enough is ill advised, virtually every important event staged and choreographed so what's the effing point of even having them unless it's George Bush and he throws up? For a flicker at least, Dennis Rodman was back in the sun. It was like the old days of the 1990s, when journalists mined every word of frequently voodoo elliptical non sequitur nonsense for Proustian profundity. If you have followed Dennis Rodman, there was something sort of serendipitous about it all, the revival of a man by some miracle still standing.

"I dream about death all the time just because I know it's coming one day and for some reason I've got to figure out which way to go, how it's gonna happen" he told Rolling Stone writer Chris Heath in 1996. "It's a weird feeling. You name every way in the world, I've thought of all of them. I've dreamed someone pulled my heart out. I've dreamed of being run over by a train. I've dreamed of getting my head chopped off."

"Isn't it all just a horrible feeling?" Heath asked.

"It makes me feel good because I'm still living. And I survived it. I keep surviving it."

He was making $9 million with the Bulls when he talked of death, somewhat ironic since no player had been better able to capitalize on the twin peaks of popularity and unpopularity.

The subsequent 17 years have not been particularly kind. He was waived by the Dallas Mavericks after 12 games in March 2000, a quiet coda at the age of 38 to a once-great career in which nobody in modern times ever played harder, rebounding an ugly act of violence in basketball with elbows twisting and arms flying, the basketball equivalent of a NASCAR crash-up dozens of times a game.

He drank too much after he quit, and partied too much, and the Rodman act, which I believe was never an act but a vital means of self-expression he was brave enough to exhibit, no longer had the freaky-deaky quality that had once made him such a spectacle. He wasn't an NBA star who cross-dressed. He was a cross-dresser who once upon a time had played in the NBA, and the difference was monumental. Nobody cared anymore.

"I love him and I feel sorry for him," Raab told me. "The rehabs never took. He is so pickled. I see him with the piercings. I do see a guy who is absolutely helpless and maybe past the point where he has much of a brain left."

He seemed inevitably headed for a tragic end, as he always knew he would be headed for a tragic end because of all the vast and painful complications: A father who left when he was 5 and has sired at least 26 other children, and a mother incapable of emotional love; growing up as an awkward and shy geek in the projects of Oak Cliff in Dallas and unmercifully made fun of because of ears that stuck out and called the "worm" because he wiggled so much when he played pinball; his guilt over his absence as a father to his own three children when he was in the NBA; his obvious sexual confusion as to who he was and who he should be in the homophobic world of professional sports; the nagging sense that he should have never been an NBA star but back as a graveyard-shift janitor at the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport. His life was a myriad of disparate pieces, once so enticing, now an odd game of hide-and-seek in which the more you found the less you wanted to find.

Until he became America's greatest ambassador since George F. Kennan first went to Moscow in the 1930s. Which has to give you faith that the American Dream is still alive somewhere.

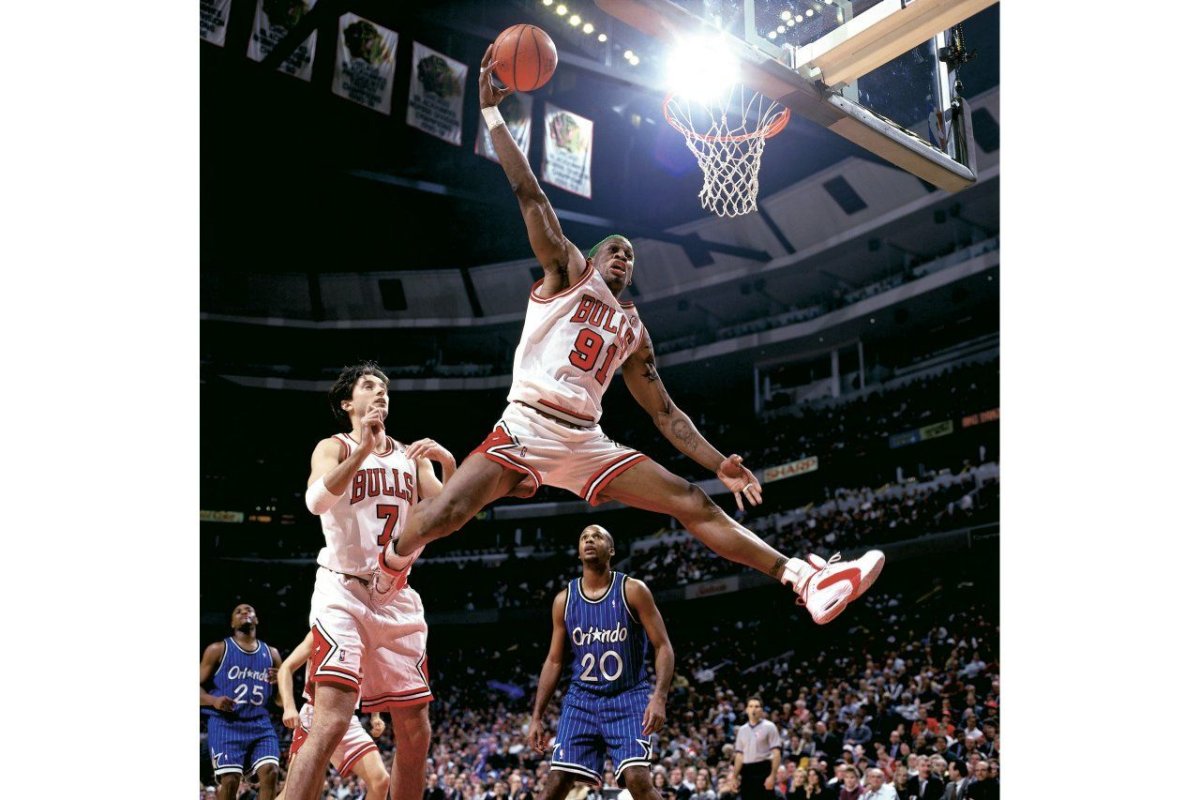

If there was an epiphany in Dennis Rodman's life—and all stories about Rodman, even the ones he tells himself, have to be read with a constant warning light—it came late at night in 1993 in the empty parking lot of the Palace of Auburn Hills, where the Detroit Pistons played. He had a rifle on his lap in his pickup and he was seriously contemplating killing himself as he relates in Bad as I Wanna Be. He loved playing for the Pistons, who had taken a shot on him, picking him late in the second round out of Southeastern Oklahoma State University in 1986, even though he was 25. They saw raw skill, and head coach Chuck Daly loved raw skill, and Rodman decided to make himself into the best rebounder in the league even though he was a small forward at 6 feet 8 and routinely gave up four or five inches to the big boys of Shaquille O'Neal and Hakeem Olajuwon.

"He played up in your space," said Michael Tillery, a longtime writer on pro basketball. "Rodman was that type of guy. The ball was just his. He just went after it. He had a sense of where the basketball was going to bounce off the rim."

The key to rebounding is not to make one big jump but a succession of quick ones, tapping the ball in your direction until you gain possession of it. Rodman could do that. He was also quick, so quick that he was able to cover a shooting guard as well as a power forward.

Plus in his heyday when he was deep in the fringes, other players just didn't want to mess with him. "They just didn't want to guard him," said Tillery. "They didn't want to be around him, this motherf--ker. All the bells and whistles of his blond hair and his tattoos and his piercings."

But on that night in Auburn Hills, he seemed trapped, suffocating. Chuck Daly, as close to a father figure as he ever had, had been fired. The team was being dismantled. But more powerfully as he said in his autobiography, "I couldn't continue to be the person everyone wanted me to be."

His life had always seemed destined for dealing drugs or robbery if it wasn't quick death. He played one year of basketball at South Oak Cliff High School on the junior varsity and then quit. He was all of 5 feet 11 when he graduated, in the shadow of his two sisters, both taller and All-American basketball players in college. He roamed the streets of Oak Cliff, homeless after high school when his mother just couldn't stand him sitting around the house all day while she worked three jobs. He took shit work. He had no future and didn't particularly seem to care about one, until he grew nine inches in two years. Basketball suddenly beckoned, and Rodman for the first time in his life actually connected to something.

After three quiet seasons with Detroit, he came alive in his fourth, winning the NBA's Defensive Player of the Year award in 1989–90 as the Pistons won the league championship. He won the same award again the following year. In 1991–92 he led the league in rebounding with a stunning 18.7 per game, one night pulling down 34 to break the Pistons team record held by the legendary Bob Lanier. It was the first of seven straight seasons in which Rodman led the league in rebounding, stunning given his height and 220-pound weight.

But then the Pistons fell apart. And Rodman fell apart. And he cradled that rifle on his lap until he decided he was exploding inside and had to unleash himself. Easily bored, with a pathological need to shake up the status quo, he came to the unveiling of the Alamodome of the San Antonio Spurs, where he had just been traded, with the patented bleached-blond hair that looked like it had been grilled. Thirty minutes late for of course (bleaching is serious business) he took the microphone and told the assembled:

"You can like me or hate me. But all I can say is, when I get on that damn floor, all I'm going to do is get solid."

Raab first profiled him for GQ in 1994 and found him "open and kind of joyful." He had tattoos before virtually anyone else in the league did. He rode a Harley. He was screwing Madonna and didn't mind talking about it. It felt to Raab that he was living out his adolescence—at the age of 32.

Raab profiled Rodman for GQ again four years later in 1997, when he had gone to the Bulls, then in the midst of winning three straight championships. He found someone different this time, no longer a big happy kid but an adult fighting demons within himself—sexual identity, a lonely isolation in which he went to strip clubs and mostly drank kamikazes by himself all night, still affable but detached, what Raab described to me as "such a distance between him and him" in which he could not fill in the gaps.

Traded by the Bulls in 1998, he lasted two more inconsequential seasons. He basically became a paid athletic prostitute after that. All athletes look to have brands, and Rodman's became alcohol. He was paid to party. Several stints in rehab at the Pasadena Recovery Center in 2009 and a sober-living facility in Hollywood seemed little more than stunts for the shows Celebrity Rehab With Dr. Drew and Sober House. He was 51 years old on his way to nowhere, becoming broke, out of the public consciousness until his trip to North Korea.

He earned no credibility for himself when he said of Kim, "He's a good guy to me. As a person to person, he's my friend. I don't condone what he does." The idea of vacationing with Kim did not go over well either. He was largely excoriated as a fool, only compounded when he went to the Vatican in a makeshift Popemobile he had custom-built in the hope of meeting the new one from Argentina.

Maybe it was all hijinks to stay in the limelight. But go back two years earlier to the annual induction ceremonies at the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. Rodman, finally getting the credit he was due with 11,954 rebounds in 14 seasons, was one of the inductees.

He walked down the stage with a blue boa and red scarf wrapped around his neck and very dark sunglasses. He removed them and gave them to his children. He stepped onto the stage in a black equestrian-style jacket with red trim on the lapels and the names "Pistons" and "Bulls" in sparkles. He cried at the podium to accept the honor, the journey of a man who if he never found peace, did find that night the acceptance he had always craved no matter how strong his "I don't give a f--k" defiance.

He thanked the four men in his life who became his father figures in the absence of a real father: former Pistons' coach Daly; former Bulls' coach Phil Jackson; James Rich, whose family had taken him in in Oklahoma; and the recently deceased Los Angeles Lakers' owner Jerry Buss.

"I can be the good guy, the bad guy, the emotional guy, the sad guy. No matter what, these guys always came and talked to me and shook my hand. It wasn't about Dennis Rodman the flamboyant, the asshole, the dickhead. It was about a guy who had a good heart."

But he also acknowledged the darkness of that heart, his selfishness with his mother in refusing to help her financially, his absenteeism as a father.

"I was burning the candle at both ends for a long time. That's why I'm surprised I'm still here. Everyone knows that. I'd like to set the record straight for the time being and maybe in the future that I can be a good father to my kids and hopefully I can love you like I did when you were born."

He meant what he said that night. The tears were not those of the crocodile. Time will only tell if he actually keeps to it. The track record is not very good. But you would not find an athlete more honest than Dennis Rodman was that night. Nor will you find one since.

Even in North Korea.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.