Reading the emotions of someone else can be a tricky business, even when it's someone we know well. But a rapidly growing field of research is exploring whether technology can be used to read our inner reactions and feelings. The idea is that if we can detect people's emotions in an objective way, we can use this information to mould and edit music and films so they deliver more of an emotional impact. Now there's a piece of technology aimed at doing just that – the goosebump sensor.

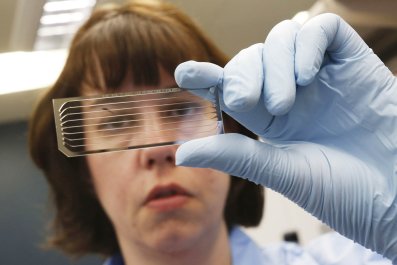

Researchers in South Korea have designed a sensor, roughly the size of a US cent piece, that sits on the surface of the skin and can detect the tiniest of goosebumps. It's an alternative to heart beat monitors and sweat sensors and its South Korean developers say that it will prove particularly effective at detecting positive emotions – the moments of elation when we hear a soaring guitar riff or a rousing orchestral piece.

Professor Young-Ho Cho at the Korea Advanced Institutute of Science and Technology (KAIST) was inspired to develop the goosebump sensor after watching an episode of I Am A Singer on MBC – must-watch Sunday night viewing in South Korea. Each week, one of the contestants, all of them veteran singers, are eliminated by an audience vote. "I wondered whether with the music and the singer there would be a way to measure the emotional reaction," says Cho. "If you were a composer, it would help you choose between different versions of the music. That's my personal motivation – understanding how you can deliver a higher emotional reaction from the audience."

The sensor developed by Cho and his team is incredibly thin – thinner than the width of a human hair – and made entirely from polymers. The slenderness and flexibility of the materials allow the detector to follow the contours of the skin as it changes when goosebumps, or "piloerection", to give it its more scientific sounding name, takes place. Tiny spirals of electrodes set into the sensor become deformed at a goosebump moment, reducing the charge they hold. It's this reduction in "capacitance", the ability of a body to store an electrical charge, that indicates the magnitude and number of goosebumps.

Cho recognises that determining someone's emotional state by detecting goosebumps will not be straightforward: some people are more goosebump prone than others. The solution, he says, is to calibrate someone's reading by giving them different levels of emotional stimulus and measuring their goosebump reaction.

As well as honing music so it's more emotionally resonant, Cho has a bigger, broader aim for emotion sensing – to give the technology in our lives the ability to react to what we're feeling, not just what we tell it. "We need to change the way machines and humans interact to include some emotional element," he says. At the simplest level, Cho says air conditioning systems could react to whether we feel hot or cold, not simply the temperature of the room. He imagines a future where the occupants of a room wear sensors that detect goosebumps, skin temperature and sweating and this is used to determine how much cold air is pumped out – not the ambient temperature of the room. Such a system, says Cho, could be available in two or three years. But he says technology that measures more subtle emotions could take a little longer to hone.

At Reading and Plymouth universities in the UK, they're trying to unmask subtle emotions using a raft of sensors, such as EEG (detecting electrical impulses in the brain) and heart rate monitors. They want to see how music they have generated using their "music composition algorithms" affects volunteers. The researchers play them different styles of music to see how they react and "learn the emotional terrain of their mind in a musical sense," says Dr Alexis Kirke, a fellow of the Interdisciplinary Centre for Computer Music Research at Plymouth University. Once an individual's terrain has been mapped, he explains, music could be played to them that would induce a specific mood – happy, relaxed, or whatever. "It would almost be like a musical extension of antidepressants or antianxiety tablets," says Kirke. It's an idea that's being taken seriously. Kirke and his colleagues were awarded £880,000 in government funding last year to carry out their studies.

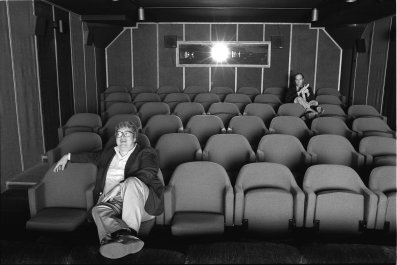

But Kirke is fairly cool on the idea of a goosebump sensor. "I'm not aware of multiple research studies on what generates goosebumps," he says. "I'm not too sure of how many times I've had chills in the cinema unless the air conditioning's been too high." But, he suggests, a goosebump sensor may be an effective way to measure extremes of emotion. "It may be that we have measures such as sweating and heart rate and we want to push someone towards the area where we know goosebumps will happen. Goosebump sensors would show when you've pushed someone over the edge."

The South Korean team envisages that their sensor could be built into a watch or wristband once they have figured out how to keep it powered up without having a cumbersome battery. Their favoured option is piezoelectrics, in which the flexes and twists of the sensor would generate power. Many experts see a day when sensors detecting our emotions will be ubiquitous – sweat detectors in our sweaters and EEG devices embedded in our specs.

Kirke says that using embedded emotion sensors, software could determine which emails or Facebook posts we're most engaged by, or angered by – suggesting products, friends, even people to date off the back of this information. "What makes me a bit nervous is that emotions are involuntary," he says. "What I type into an email or Facebook post is voluntary, but my internal state is involuntary. So what are the privacy issues with emotional data?"

There's no doubt we'll soon be facing some tough judgement calls about having emotion sensors embedded in our lives – where they should be and what they should record. After all, there's likely to be bits of all of us – perhaps our tastes, our ambitions or our desires – that we don't want others to discover.