Graduate students across America are forming unions, holding protests and, in some cases, being arrested to draw attention to their cause. What is it they're after? In many cases, it's a livable wage.

The relationship between universities and graduate students is arguably beneficial to both parties, but it's also rife with tension. A university provides the pathway to the careers students seek, while students assist with research, teach undergraduate students and fill a number of other gaps on campus. Essentially, the fight for compensation rests heavily on a simple question: Are graduate students employees?

In 2016, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) ruled that student assistants at Columbia University in New York City, did in fact fall under the definition of "employee." However, many universities, including Loyola University Chicago, Washington University in St. Louis and the University of Pittsburgh, have maintained that the students are students only.

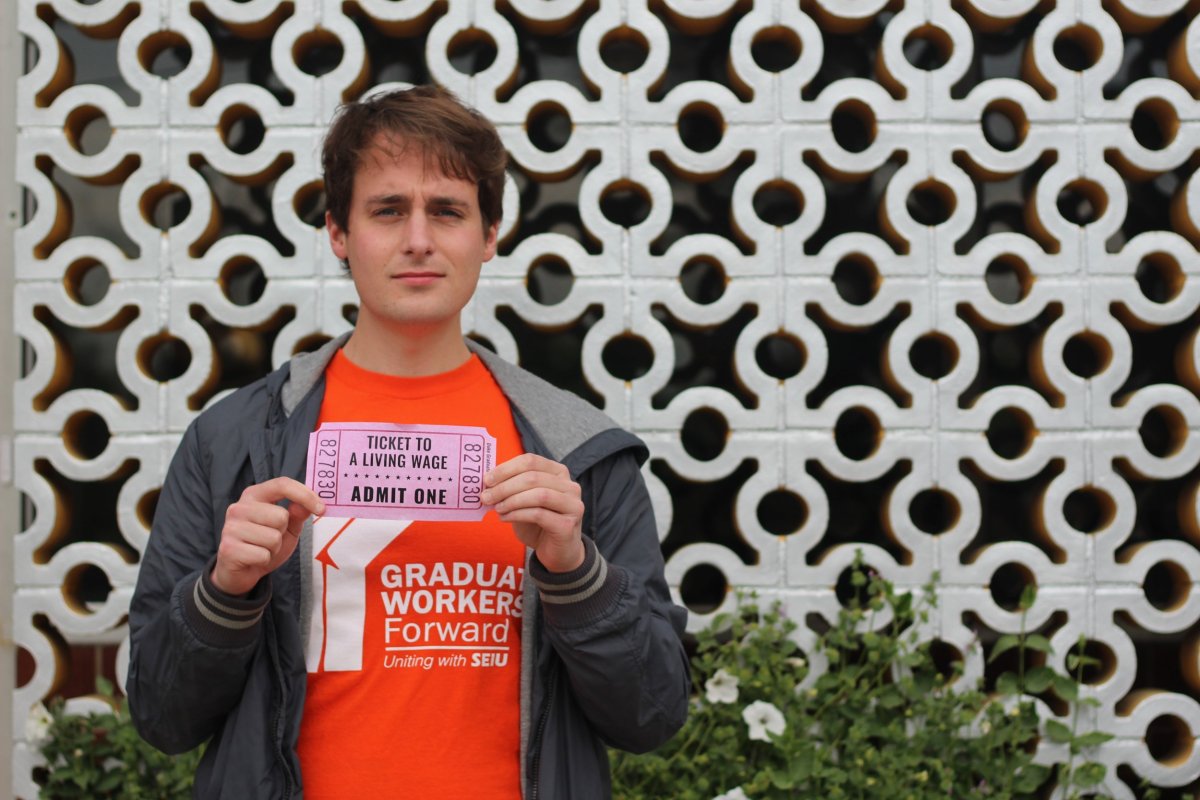

Loyola University Chicago

Jean Clifford, 31 and in her fourth year of Loyola University Chicago's Ph.D. program, told Newsweek that the students voted in favor of unionizing in 2017, which she credited to being the only way they could make their voices loud enough to effect change. Two years later, they're still pushing for a living wage in the form of a $26,000 stipend.

"We want to be giving Loyola really high-quality teaching and scholarship, and they are not giving us the resources that allow us to do that," Clifford said.

Packages can vary, but Clifford's includes tuition remission, health insurance and a $20,000 stipend for the year. In exchange, graduate students agree to a number of responsibilities, which could include teaching courses, grading undergraduate work, completing theses or being a research assistant.

"We're working 60 hours a week; 20 of those hours are designated to be for another faculty member, but we are still responsible. Loyola is paying us to be scholars," Clifford said. "So the work that I do on my dissertation is my research, but I'm doing it as part of what I've agreed to do for Loyola."

The issue of proper financial compensation, Clifford said, came down to the question "Can you survive on the amount of money that you get in your bank account to do the amount of work that we're asked to do?" With $18,000 for the year as the contract provides, Clifford answered "no."

Along with scavenging office events and department parties for free food, even resorting to surviving off leftover sheet cake for days at a time, Clifford amassed more than $130,000 in debt to close the gap between what she needs to live and her university-provided stipend. Given her age and the pay schemes of her chosen profession as a professor, she doesn't expect to ever pay it off.

"Consistent with Catholic social teaching, it is just and acceptable to recognize the important relationship Loyola has with our graduate assistants, address their needs and give them a voice, but it need not be through a union," the university told Newsweek. "Graduate assistants are admitted to Loyola as students based on their academic qualifications, and when they leave us they receive an academic degree. They are students in every sense of the word."

On Monday, several students were arrested for blocking an entrance to a building during a sit-in. The protest reinforced calls for the university to recognize the student union and bargain for a contract. Despite the pushback from administrators, Clifford remained hopeful that change would come for the graduate students.

"In the spirit of not wanting to jinx it, it's hard to answer that, but I will say that after our action at Loyola on Monday I am more and more optimistic that the university will listen to what we're saying," Clifford said.

Washington University

In the third year of her Ph.D. program at Washington University in St. Louis, Lacy Murphy's typical week includes meeting with undergraduate students outside class, editing papers, overseeing exams, grading papers, being a peer mentor in her department, facilitating scholarly discussions—and the list goes on. For compensation, Murphy told Newsweek, she's given health insurance with a $5,000 out-of-pocket maximum, and an 11-month stipend of $2,336 a month.

"This would cripple our institution if graduate workers weren't available for teaching responsibilities," Murphy told Newsweek. "We wouldn't be able to offer the amount of lectures that we do [or] open up the class size for the amount of lectures that we do."

Murphy is a teaching assistant for a "gateway" course that's a requirement for every architectural student. With hundreds of students each year needing the class, without the use of graduate students like herself, Murphy said the "architectural program by itself would be completely undone."

In the discussion of compensation for graduates, it's common to note that many students' packages include tuition remission. It's a fact that can't be dismissed and bears weight on a student's ability to pursue higher education. However, Murphy explained, students earned those scholarships, so, tuition remission isn't a satisfactory payment for their additional work.

"We're the brightest in our fields and we have a lot of potential, and it's not like we aren't deserving of those scholarships," Murphy said. "We're deserving of the academic scholarships on a purely academic level, on top of being compensated for the labor that we're doing for this university."

On Monday, following the arrest of several students occupying Chancellor-elect Andrew Martin's office, graduate students set up a tent city on the lawn in front of the building, where they remained on Friday. Fair financial compensation in the eyes of the graduate student union, Murphy told Newsweek, would be $15 an hour, or $31,000 a year.

"I'm hopeful, but honestly sometimes I think someone will have to die, or someone will have to become homeless, or someone will have to experience food scarcity, go on food stamps, before this university makes a change," she said.

Duke University

Duke University announced on April 11 that starting the 2022-2023 academic year, Ph.D. students will receive a 12-month stipend of $31,160 during their five-year guaranteed funding period.

"This is a huge victory that will really improve the well-being and the lives of future Ph.D. students, but there is still funding shortfalls for current Ph.D. students," Matthew Taft, a Ph.D. student at Duke, told Newsweek. "So, certainly we'll be seeking to have discussions with Duke about the timeline of this implementation, but those discussions are not yet being had."

In his fourth year of Duke's Ph.D. program, Taft, an international student from Australia, is an assistant editor for an academic journal, and when he's responsible for teaching courses, it can require up to 20 hours of work a week. Taft has a nine-month stipend of $23,500 and credited having a partner with a second income for why he hasn't had to take out loans. But like so many other graduate students, he experiences a great deal of financial stress, which carries over into the classroom and affects the undergraduate program.

"Not knowing how you're going to survive is incredibly emotionally and mentally taxing, and this emerges throughout the year … that really impairs your ability to teach in a way that you would like to," Taft explained. "Not being paid a living wage undermines the quality of teaching that undergraduates receive at this institution, and the quality of research that Ph.D. students can produce."

Taft added that without the level of graduate student work that's taking place at Duke, the university wouldn't be able to run in its current structure, saying it "fundamentally" relies on graduate student labor.

Duke's graduate student union is asking to be paid a living wage as set by the city of Durham, North Carolina, where the university is located. It's not an "exorbitant sum," Taft said, just $15 an hour, or $31,600 a year. However, the union doesn't have formal bargaining rights, so the school has no legal obligation to meet them.

"Duke believes that graduate students who engage in research and teaching as part of their programs of study are students, not employees," the university told Newsweek. "As members of an academic community, graduate students have a unique relationship with faculty and each other that is based on education, not employment."

University of Pittsburgh

Thursday at 5:00 p.m. EST, the final ballots were cast, determining whether graduate students at the University of Pittsburgh would unionize. The outcome won't be determined until April 26, but Caitlin Schroering, a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate in the sociology department, told Newsweek she was hopeful the votes would be in favor of the union, and that only a few students she'd spoken to were opposed to it.

"It was kind of surprising to me when I got to Pittsburgh, which has this reputation for being a union town, that we were not unionized," Schroering said.

While financial compensation is part of the proposed union's platform, Schroeing said that for Pittsburgh graduate students, it was more about transparency in how decisions were being made. She said they weren't given a voice when it came to funding, teaching assignments and nominations for fellowships, all of which affect their lives.

Nathan Urban, vice provost for graduate studies and strategic initiative, told Newsweek that over the past five years there has been about a 13 percent increase in stipends for graduate students. While Urban considered the partnership and collaboration between students and university "very, very important," he said the students are just that.

"Principally, first and foremost students, they are here to get an education, and we think it's really important that the most important thing we provide to our students is a set of opportunities for their futures," Urban said. "We want to do the best job possible in educating and training our students."

Regarding the argument that graduate students are solely students and not workers, Schroering said it sent a message that her contribution to the university wasn't valuable.

"It's incredibly frustrating for me, and it's disheartening, because what it says to me is they don't value the work that I do for this university—and it is work," Schroering said.

Clifford, Murphy, Taft and Schroering all attend different universities in different parts of the country. While their goals may vary, their shared belief is that graduate programs don't just affect graduate students, they impact the university as a whole.

"Universities are more prestigious when they have healthy graduate programs," Clifford said. "It counts in their favor in their scholastic reputation, and one of the ways you get good graduate students is you offer them competitive packages."

This article has been updated to clarify Murphy has a $5,000 out-of-pocket maximum, not deductible.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jenni Fink is a senior editor at Newsweek, based in New York. She leads the National News team, reporting on ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.