Mickey Hart considers himself a "rhythmist," but it's not only because of his legendary drumming. "I have a rhythm-centric view of everything," says the former drummer for the Grateful Dead. "The whole universe operates with rhythm, and we are all rhythmic animals in it."

After Dead leader Jerry Garcia died in 1995, Hart eventually went on to co-form Dead & Company, which will begin the summer portion of their 2018 North American tour in a few weeks. (Click here for all the dates.) In April, at the American Museum of Natural History's Hayden Planetarium in New York, he indulged in another of his "enthusiasms," performing "Musica Universalis: The Greatest Story Ever Told, " a thrilling sonic and visual voyage spanning 13.8 billion years in 30 minutes, from the Big Bang onward.

The show, a collaboration between Hart and the museum's director of astro-visualization, Carter Emmart, featured the Dead member playing an electric instrument he calls the Beam. The 8-foot aluminum instrument, which was modeled after Pythagoras's monochord, has 13 bass piano strings and various pickups and amplifiers. The coolest part of the performance featured a giant MRI of Hart's brain, revealing the effects of all that sonic stimuli.

The percussionist and musicologist spoke to Newsweek about how he came to love drumming, as well as his years investigating how rhythm and vibration affect our brains.

In 1991, the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging invited you and neurologist Oliver Sacks to testify regarding how rhythm can help people with Alzheimer's disease and dementia.

We noticed that rhythm is a great stimulus for reconnecting the broken neural pathways. The movie The Music Never Stopped was based on Oliver's essay "The Last Hippie," which tells the story of someone who hadn't spoken a word since the late '60s. Oliver brought him to a Dead concert. All of a sudden, he said, "Where's Pigpen?" Pigpen used to be [the Dead's] lead singer.

Who's your current go-to neuroscience guy?

Adam Gazzaley, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Francisco, is finding out what rhythms do to what parts of the brain. What does a healthy cell look like sonically? What frequencies could damage it? He's a Deadhead, by the way.

You've spoken about the "rhythmic entrainment" that keeps the universe—and us—running smoothly.

We're all embedded in a universe that is rhythmic. As Carl Sagan said, "We are made of star stuff." When you're healthy, there's a good rhythm—your heart and lungs are pumping, your blood is flowing, you're in sync. Good rhythm would be peace.

Look at the Dalai Lama: Talk about a rhythm master! The Chinese destroyed his culture, and he doesn't hate them…. I would hope our president would learn a bit from the Dalai Lama. It's very sad. Mr. Trump needs a lot of schooling. He doesn't know how to dance. He has bad rhythm. I don't see anything good coming from this president.

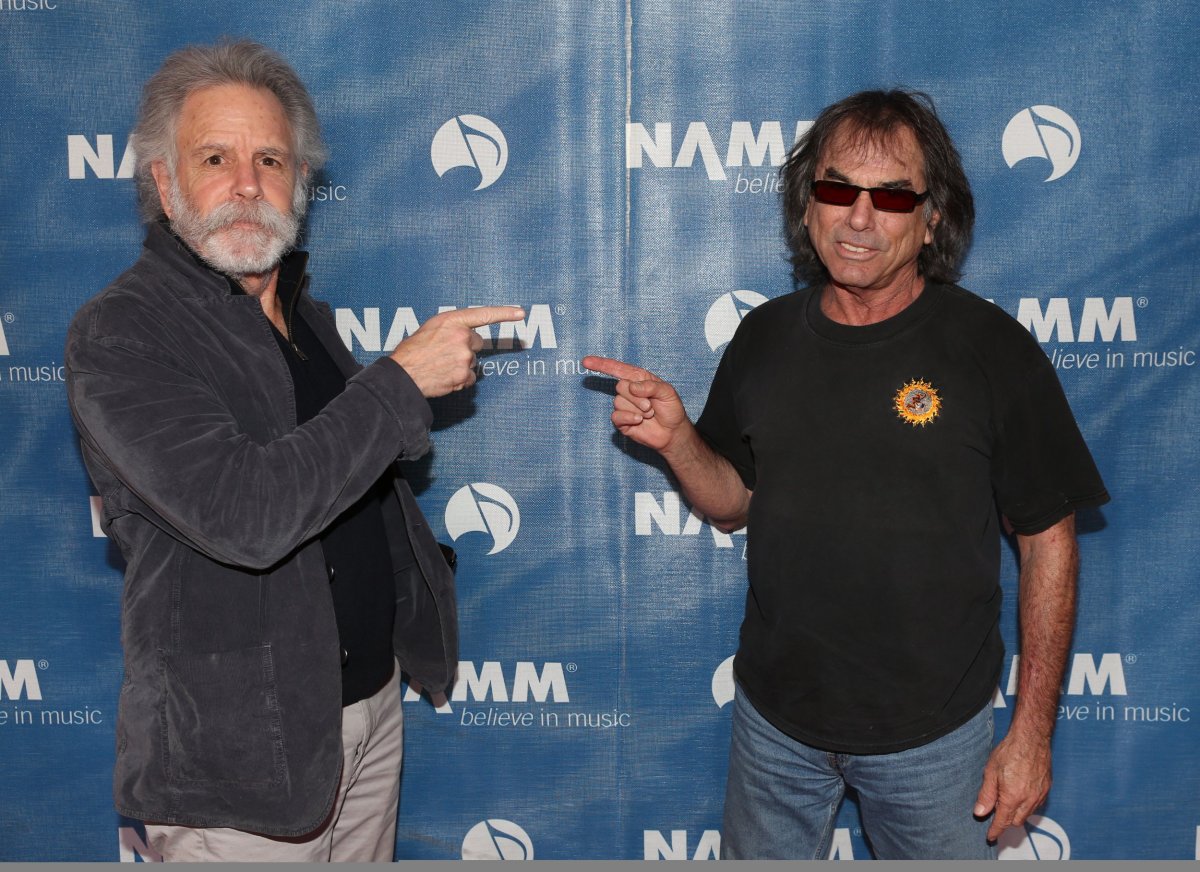

A major part of the Dead's long, trippy jams are the two-drummer formula that you and your fellow "rhythm devil," Bill [Kreutzmann], developed. How does that work?

We don't know, and we don't want to examine it too much. We're able to split half the band up with one drummer, and the other half plays with the other drummer, and we all meet at the pass. Then there's the power of playing together in unison. And when you're two drummers, there's a loss of ego. Bill and I are kind of tied at the heart—we're still great friends.

You and Jerry were quite close too. What did you guys do for fun?

When we were in New York, we would listen to jackhammers and buildings being destroyed by demolition balls. We were "noise-icians." Jerry always encouraged what he would refer to as my "enthusiasms." What we are talking about now would be an enthusiasm.

What are your earliest memories of drumming?

I started when I was 3 or 4, using a practice pad. Eventually, I got two little bongo drums. When I was 12 or so, I went out on the beach, where the football players would have bonfires. One night, after they were gone, I started playing the drums, and two gals came up and started dancing around the fire. I thought, I want to do this the rest of my life. You know, music is a mating ritual, really. It propagates.

I've read some interviews crediting your mother for having your back when you played drums at home.

You have to have a good mother if you're a drummer. My mom used to stand at the door when this nice fellow, a truck driver who lived downstairs, would run up while I was playing "Sing, Sing, Sing," one of [drummer] Gene Krupa's great songs with Benny Goodman. She would stand there with a broom: "Over my dead body!"

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.