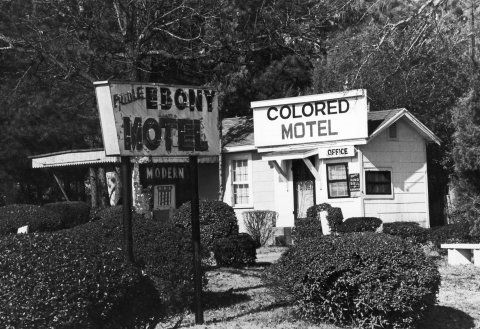

The year is 1940. You are in a '37 Buick, driving west on the Dixie Overland Highway. You plan to take it all the way to California, but as things stand, you might not even make it to the Texas border. For you are black, and you are deep in Alabama, and night is coming.

This is the land of strange fruit: Elizabeth Lawrence, an elderly black woman who'd chastised white children for throwing rocks at her, lynched in 1933; Otis Parham, 16, set upon by a mob that couldn't find the perpetrator of an alleged attack on a white man in 1934. They killed Parham instead and threw his body into a ditch. You don't have to know the names of Alabama's recently murdered to feel the presence of their ghosts in the roadside thickets of longleaf pine.

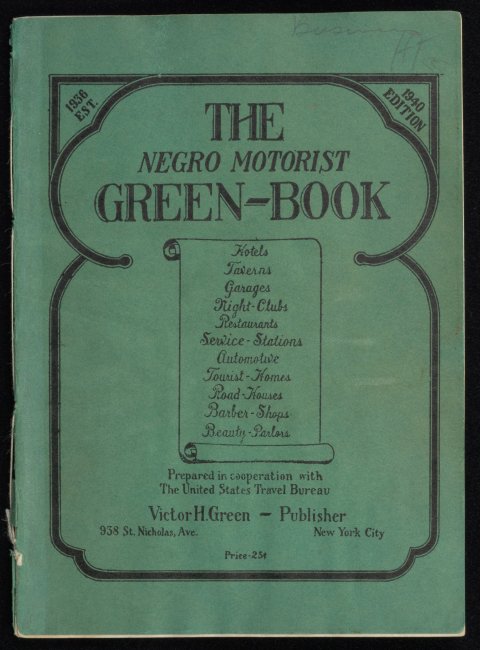

With the day's light faltering, you pull over and retrieve The Negro Motorist Green Book from your Roadmaster's glove box. It is 48 pages of practical scripture, offering safe passage through the United States—where you can sleep, eat and fill your gas tank. The 1940 edition of the Green Book offered several options for safe harbor in central Alabama from the Ku Klux Klan, not to mention less deadly manifestations of hatred. Some of these are hotels that will allow black guests, like the Fraternal in Birmingham. Others are private homes, such as that of Mrs. G.W. Baugh, at 2526 12th Street in Tuscaloosa (private homes are almost always listed under the name of a female host). The Green Book also lists a few restaurants, clubs, garages and beauty salons. In Augusta, Georgia, you are welcome at Bollinger's liquor store—but nowhere else.

The number of listings will grow, especially after a brief hiatus in publication during World War II, as more and more people write in with suggestions, crowdsourcing a compendium of black-friendly sites across the nation. In 1957, North Dakota would be the last state in the continental United States covered by the Green Book. In 1964, Hawaii became the 50th state in the guide, which that year also featured entries for Europe, Africa and Latin America.

Thus what began in 1936 as a barebones aggregation of New York–area advertisements would eventually create what the historian Jennifer Reut calls an "invisible map" of America. The guide's creator, Victor Hugo Green, had recognized that such a map was necessary. But he also hoped that his work would eventually be obviated by social progress. Later editions of the Green Book contained an introduction with this optimistic passage:

There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment.

The Green Book did, in fact, cease publication in 1967, three years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act. But equality legalized wasn't equality realized. A 2012 survey found that 40 percent of waiters polled in North Carolina admitted to discriminating against black customers. Earlier this winter, a Quality Inn in Maryland was sued because black guests alleged "hotel workers demanded that black guests show their meal tickets to get breakfast while ignoring white and Asian guests."

As for that ancient sin of driving while black? It remains, ameliorated only slightly by time. "My dad told me when I was driving to be extra careful," a black administrator at Pennsylvania State University told the BBC last year. "It goes back to how officers will look at you as an African-American driving."

National statistics regarding the perils of Driving While Black are frustratingly elusive, but those that do exist all point to a significantly higher rate of police stops for blacks than any other ethnic group. Sometimes, those stops turn deadly, as in the cases of Philando Castile, Samuel DuBose, Walter Scott and Sandra Bland, all of whom died as a result of traffic stops.

The Green Book is obsolete. Its lessons are not.

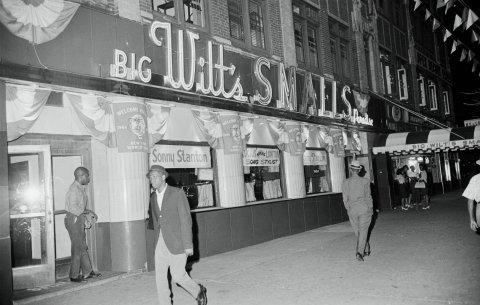

Harlem on the Prairie

On an exceptionally cold morning this winter, I walked into an International House of Pancakes on 135th Street in Harlem. I'm a fan of IHOP's powdered sugar crepes, but that wasn't why I'd trooped uptown. I'd come to see what remained of Smalls Paradise, which occupied the ground floor of this decorous terra-cotta building from 1925 until 1986. More than a music venue, Smalls Paradise was central to African-American culture in the 20th century. Malcolm X worked there as a waiter in 1943: "No Negro place of business had ever impressed me so much," he wrote in his autobiography of first entering Smalls. Fats Waller and Ray Charles performed there. It was also a site of racial mixing unique to the Harlem Renaissance: The early civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois, for example, was feted at Smalls on his 83rd birthday by Paul Robeson and Albert Einstein.

In later years, the club was owned by basketball great Wilt Chamberlain, but he shuttered it in 1986, as the neighborhood was pummeled by poverty, drugs and neglect. The IHOP opened in 2004, when Harlem's fortunes were ascendant once again. It is supposedly one of the most popular IHOPs in the United States, but it is otherwise no different than its 1,650 peers. There is no sign, inside or out, that this was ever anything but a pancake restaurant.

After a few minutes of waiting, I watched as a diminutive, well-dressed woman walked into the restaurant. Candacy Taylor was not there to eat sugary crepes either. Taylor is trying to catalogue every Green Book site across the United States. She wants to make that invisible map visible again.

Smalls Paradise was such a site, one of hundreds in Harlem. The windows of the IHOP looked out at a shabby apartment building from which a faded marquis for the Hotel Fane extended like a vestigial limb. The Hotel Fane advertised in the Green Book, touting its presence in "the Heart of Harlem," as well as both hot and cold water in the rooms. Also in the Green Book was the desegregated YMCA on 135th Street—"the living room of the Harlem Renaissance," as it was known—where Malcolm X lived for a time. Taylor estimates that there may be as many as 700 Green Book sites in New York City, some of them famous, like the Savoy Ballroom, but most having long faded into oblivion: a millinery on Manhattan Avenue named Beulah's, a tavern called the Colonial Krazy House, on what I imagine was a stately stretch of Bradhurst Avenue in Harlem.

The Green Book created what Taylor calls an "overground railroad," used by the progeny of those who may have relied on that other, more famous railroad offering passage out of slavery. The Underground Railroad promised freedom; the Green Book promised something just as fundamentally American: leisure.

Taylor has spent the last several years photographing Green Book locations for her website while planning a much larger project she hopes will grant the Green Book the cultural prominence it deserves. Her task is made difficult by the fact that each edition of the Green Book was often significantly different from those before and after, depending on the shifting landscape of prejudice in each state. An out-of-date listing—a motel that welcomed blacks suddenly shuttering—could spell doom for a traveler stranded in the thick of Mississippi.

Taylor went through all 22 editions of the guide to create a list of 4,964 sites—and she's gone through only about half of the nation. She believes that perhaps 25 percent remain standing in some form, like the IHOP in Harlem, while only about 5 percent operate as they did in Victor Green's time. A few are obvious and easy to find, like Clifton's Cafeteria in downtown Los Angeles, which recently reopened after a $10 million renovation, once more serving all those who reach the western terminus of Route 66, though it's pay-as-you-wish policy hasn't survived into the 21st century. But some are even more invisible than they were on Green's "invisible map," retreating into historical obscurity. There is Murray's Dude Ranch, in the high desert of Southern California, notable for catering to an African-American clientele. Black cowboy films like Harlem on the Prairie were filmed there . Today, it is just an expanse of sagebrush.

Other Green Book stops live on in shabby anonymity. The Hayes Motel, in the historically African-American section of South Central Los Angeles, opened in 1947, 18 years before an incident of police brutality led nearby Watts to erupt in fiery frustration against the city's reactionary leaders. The 1992 riots, in response to the acquittal of the four police officers who'd beaten motorist Rodney King, began a few blocks away. Somehow, the Hayes Motel remained in operation, but the turbulent times took their toll. When Taylor visited with a reporter for the Los Angeles Times, a telling sign greeted potential guests: "No drugs. No Prostitution. No Loitering. No Trespassing."

Taylor—who is writing a book on the Green Book, is in talks with the Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service and is creating an interactive map with partners that may include Harvard, the New York Public Library and Google—isn't waiting for someone to invest $10 million in the Hayes Motel. But she believes it has a story worth commemorating, as do all its fellow Green Book survivors. She hopes to reclaim a forgotten chapter of African-American history, partly because it is our history and does not deserve oblivion any more than Millard Fillmore's log cabin, but also because there were things we should have learned then but did not.

"This is a cautionary tale," she says. "This is still with us."

'Travel Is Fatal to Prejudice'

Victor Hugo Green was born in New York City in 1892. That year, there were 161 lynchings of African-Americans across the United States, an inglorious number never surpassed. Green grew up in New Jersey across the river from New York City and worked as a letter carrier. In 1918, he married Alma Duke, and they moved to Harlem.

The Green Book was born in part because of Green's marriage to Duke, a native of Richmond. "With Green's wife being from Virginia, he decided to make trips less humiliating and reached out to fellow mailmen all over the country," Green Book historian Calvin Alexander Ramsey told The New York Times in 2010. Ramsey added that Green had a friend who told him Jewish travelers, themselves often victims of discrimination, had guidebooks to make trips through hostile territory safer.

Today, any edition of the Green Book is a prized rarity. The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture recently bought a 1941 edition at auction for $22,500, or 90,000 times more than it originally cost: i.e., a quarter. The original Green Brook, from 1936, is the most elusive of all, with no known extant copies or even images of that edition.

That second issue of Green's guide was only 16 pages long and little more than a collection of advertisements for New York–area hotels and restaurants. The book's introduction is printed on the front cover: "Let's all get together and make Motoring better." Motoring was becoming central to the American way of life when Green embarked on his project in 1936. The Triborough Bridge opened in New York that summer, the Bay Bridge in San Francisco that fall. Both were explicitly designed for vehicular traffic, funneling the residents of these large, coastal cities into the interior of the country. Highways began to stitch together distant parts of the country—Route 66, the "Mother Road" of automotive travel, opened in 1926. That same year, Route 50 traced a path from Maryland to California.

Gretchen Sorin, a historian of African-American travel who directs the Cooperstown Graduate Program of museum studies at the State University of New York College at Oneonta in upstate New York, says African-Americans back then were especially invested in automobile culture. She asked if I'd ever heard the stereotype of the young black male who lives with his mother but sports a flashy Cadillac with gleaming rims. I answered that I had, recalling Chris Rock's joke from a 2004 comedy special—"Maybe if we didn't spend all our money on rims, we might have some to invest"—which suddenly seemed just a little less funny. Sorin says this stereotype was rooted in the cruel reality of housing discrimination. Unable to buy real estate, many African-American families made an automobile their biggest purchase.

There was also safety in size, as well as speed. "It was harder to turn over a big car," Sorin says. "If you had a car that had a lot of power, you could get away." In 1955, the Reverend Moses Wright testified in a Mississippi courtroom against the two white men who'd murdered his grand-nephew, Emmett Till. Fearing for his own life, Wright fled in a '46 Ford sedan, in which he slept that first night. He later sold the car to buy a train ticket to Chicago, but without recourse to a vehicle, Wright would have also been lynched.

For middle-class African-Americans, travel down the nation's new roads and highways could serve as proof they were no different from their white counterparts. They would be, in a sense, ambulatory examples of black progress. Some editions of the Green Book featured a quote from Mark Twain: "Travel is fatal to prejudice."

The Green Book was always somewhat coy about its own purpose, maybe because that purpose was so obvious, or maybe because it was so monstrous, it was better relegated to the margins. The guide is generally free of politics or commentary of any kind. In the 1947 edition, there is a listing of "Negro colleges," as well as an advertorial apparently reprinted from The New York Times that alludes to the participation of African-American soldiers in World War II: "The Negro...shared the mud, the danger, the sweat and the tears. Now he has the right to continue his interrupted education if he wants to do so."

But even such tame expressions of race recognition are rare. The goal is pleasure, not enlightenment. The ads show graceful hotels and suggest sumptuous meals. There isn't any fear-mongering, and warnings to stay out of places are similarly infrequent. Green's strongest language was reserved for road safety, in a recurring tongue-and-cheek item called "How to Keep From Growing Old" (e.g., "Always speed"; "Never stop, look or listen at railroad crossings"). Green wanted to treat his African-American readers like ordinary travelers, though of course the raison d'être of his book was that they were anything but. The first year in American history since 1882 without a recorded lynching of a black person was 1952. In a sense, Green's book was a hedge against racial progress.

A deal with the Esso chain of gas stations allowed Green to distribute his guide more widely, so that by 1962 there were 2 million copies in circulation, with an annual print run of about 15,000 (Taylor warns that both of these numbers may be inexact). In 1947, he started his own travel company, prosaically named the Vacation Reservation Bureau. Its offices were above Smalls Paradise, where there is today, looming over that IHOP, a charter school named after Thurgood Marshall, the civil rights lawyer and Supreme Court justice who did so much to dismantle segregation in America. Because of him and fellow activists and jurists, the work Green did in that second-floor office eventually became unnecessary.

"I think what's exciting about the Green Book is that it literally did save lives," Taylor says. "But then there was this other side where it just gave black people the freedom to experience America like everybody else."

'American Carnage'

I first met Taylor in Los Angeles, two days after Donald Trump was elected president of the United States. That night, she was giving a talk on her project at the Petersen Automotive Museum. An exhibition hall of priceless Bugattis filled with a crowd that seemed hearteningly—if superficially—diverse.

Taylor likes to tell a story about driving with her mother through Houston in 1978. By the side of the road, a chain gang was working. A question bothered Taylor, which she posed to her mother: If slavery was over, then why were all the men in the chain gang black?

"She had no answer, or maybe she just didn't know how to explain institutional racism to a 7-year-old," Taylor wrote in The Atlantic last year. "Either way, it was painfully obvious to me that there was a problem. I've been questioning the existence of racial equality ever since." Taylor calls herself a "cultural documentarian," which means she writes—books on coffee shop waitresses and a guide to Route 66—but also takes photographs, as she has been doing for her Green Book project, and creates multimedia exhibitions, like the one she did on ethnic beauty salons. While researching the Route 66 guide, Taylor noticed most representations of travelers on the Mother Road were of "the lily-white suburban family" packed into an Airstream trailer. Black travelers didn't seem to exist. "I knew there were all these narratives that were missing in that story," she says.

As we watched the Petersen exhibition hall fill up, I mentioned the astonishing outcome of the election. Taylor is an intense, graceful woman who has the confident manner of a college professor and doesn't seem to enjoy small talk. She countered that the outcome wasn't astonishing to her. She'd spent a portion of the previous two years driving across the country, systematically trying to track down every single building from the Green Book that was still standing: every private house that welcomed travelers of color, every roadside diner, every gas station. Los Angeles, where she was living at the time, had 224 sites.

Between Clifton's and Smalls Paradise, there was an archipelago of safe sites across the continent, and these presented the greater challenge. Such establishments were often located in marginal areas that have only further deteriorated in the last five decades, whether because of white flight, freeway construction, "urban redevelopment" or, more likely, some noxious combination of those factors. Searching for the past, she also saw the present. "You don't think you're in America," she says of visiting the rougher sections of Chicago, where black culture had once thrived. "I would be in tears." Though she says she's not "shrinking flower," Taylor started to carry a stun gun after she was nearly assaulted by a homeless woman on Skid Row in Los Angeles. She saw, in other words, the "American carnage" Trump would correctly diagnose but incorrectly attribute. The greater fault is not with Mexico or China, but with ourselves.

Beautifully and Tragically

The Green Book's return to cultural relevance began a decade ago, with a 2007 traveling exhibit called the "The Dresser Trunk Project," which relied heavily on Green Book to highlight the travails of traveling in the era of Jim Crow. The following year, Americans elected their first African-American president, leading pundits to declare that the nation was entering a post-racial period of universal comity.

In the spring of 2009, a Tea Party protester who couldn't have been older than 14 carried a sign that explained the principles of "Obamanomics," which were "Monkey see, monkey spend." Many other signs hoisted by Tea Party protesters in their days of right-wing rage urged Obama to return to Africa, though he'd never lived there.

In 2010, as the brief post-racial moment waned, Calvin Alexander Ramsey published Ruth and the Green Book, a children's book about an African-American girl who travels with her parents from Chicago into the segregated South. She thinks, at first, that Jim Crow is a flesh-and-blood villain, only to quickly learn otherwise. The journey becomes easier—pleasant, even—after her father is advised by a bow-tied gas station operator on the Georgia border to buy a Green Book. "It made me sad that some people were mean to Negroes," Ruth concludes. "But it helped to know that good black people all over the country had pitched in to help each other."

The Green Book became the object of widespread fascination in 2015, when the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library digitized its holdings and made them available online. Librarian Maira Liriano, who was responsible for that project, first heard about the Green Book in an NPR segment six years ago. Sometime after that, she was foraging in the Schomburg archives and discovered a copy of the guide. "Travel guides in general tend to be pretty rare," she tells me, and that is especially the case with one like the Green Book that were updated each year. Those who used it would discard old versions for each new one. "You didn't want to put yourself in danger by having something that was out of date."

Reut, the architectural historian, is working on a project called Mapping the Green Book, an online cartographic version of Taylor's work, while Sorin, the Cooperstown professor, is finishing a documentary with Ric Burns about the Green Book and driving while black. She says that while the Green Book highlights the struggles of African-Americans, it is also evidence of a broader integration of American society. The African-Americans who intrepidly set out with Green Book in glove compartment "laid the groundwork" for interracial couples, ethnic minorities and gays and lesbians who wanted the freedom already enjoyed by whites.

I first learned about the Green Book from 99% Percent Invisible, a popular podcast about American history and culture. The 20-minute program concluded with Taylor in the basement of the central branch of the Los Angeles Public Library, which has 11 copies of the Green Book in its collections. "They're just little jewels," Taylor says, holding one. "I mean, I just buzz with this kind of good energy."

I had read plenty about the Green Book before I got to see one. But I finally did at the Schomburg Center, where Taylor was a scholar-in-residence before taking a similar position at Harvard. Several librarians met us in a conference room; on a large table were several editions of the Green Book. They were small, and the smallness felt acutely poignant in that first moment of contact. I understood for the first time how fragile was this "invisible map" Green had stitched together, how vulnerable the people for whom it was meant.

Taylor and the librarians watched as I flipped through the books with what may have been slightly unprofessional glee. I'd handled rare books before, including a First Folio of William Shakespeare's plays that a Dartmouth librarian placed into my ungloved hands. I like rare books even more than I like IHOP's powdered crepes; standing before the Gutenberg Bible or John James Audubon's Birds of America is, for me, an ancient sugar of which there can be no excess.

The Green Book isn't quite as rare or valuable as those volumes, yet there was a familiarity to the booklets that multiplied their power. I wasn't just holding a rare book; I was holding a rare book that was American, beautifully and tragically so. It wasn't anywhere near as hefty as a modern-day Lonely Planet . Despite some fine cover art, it lacked the modernist design elements Mad Men taught us to prize. The Green Book couldn't afford any such flourishes, neither literally nor in the grander sense, because its most basic mission was to ensure survival.

#LaughingWhileBlack

Travel has been the site of many conflicts, because travel forces people to interact in unpredictable ways. This is sometimes its great pleasure and often its greatest danger. As long dormant racial animosities have returned with grotesque force, Victor Green's wish for his guide to become obsolete has attained a new melancholy quality.

In August 2015, 11 members of the Sistahs on the Reading Edge book club got on the Napa Valley Wine Train. All but one of the women were black. The tourist train, which starts in the city of Napa and wends through the fertile hills of wine country, is popular with day-trippers who want to take in the views and cabernets without having to bother with driving.

Before the train left, a Wine Train employee asked the women to keep their voices down, according to an account later provided by Lisa Johnson, a member of the book club. The women were asked to quiet down again but continued in what was reportedly a boisterous but harmless conversation between old friends.

The crew apparently felt otherwise. In St. Helena, they asked all of the women to leave the train. The experience, which Johnson later described, left her shaken: "That was the most humiliating and embarrassing thing I've ever experienced in my life. To be paraded through all those cars, all those passengers looking at us, wondering what did we do that was so bad that we were being escorted off that train." She posted on Twitter with the hashtag #LaughingWhileBlack.

The story became a national outrage, in part because it seemed so obvious that being a little loud, a little tipsy, was the whole point of the wine train. The women sued and eventually won an undisclosed settlement, but the episode was a reminder that while the indignities of traveling while black may not be what they were in 1940, indignities remain. In fact, after a period of quiescence, they seem to have gotten worse. The migration of many travel services to the internet has allowed for new subtler forms of discrimination to flourish. Last fall, a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that some drivers for Uber and Lyft engage in discrimination. Customers with African-sounding names, for one, waited longer for a ride than those with "white" names.

Writing of the Green Book's "renaissance" in the age of #BlackLivesMatter, Makiba Foster, assistant chief librarian at Schomburg, argued that "in order to fully grasp and understand the importance of this 80-year-old publication, we must also truly grapple with how Black motorists are still being treated by the police and their fellow citizens."

Discrimination is especially pronounced on Airbnb, the peer-to-peer vacation rental service. Last year, an African-American man named Rohan Gilkes wrote on Medium about trying to rent a house in a picturesque part of Idaho where a white friend lived. He tried to book several houses, only to find owners either unresponsive or claiming, suddenly, that they wouldn't be away during the time of his planned visit.

In Atlanta, a black couple that rented an Airbnb house found themselves confronted by a host of police, neighbors having apparently figured the renters were thieves. That couple started a travel site specifically targeted to black travelers: Noirbnb.

Victor Green's book remains relevant even if the last drop of beer dribbled out of a tap at the Kentucky bar in Pasadena, California, decades ago. That's because the Green Book is not so much an object as a spirit, a version of Manifest Destiny that has nothing to do with triumphalist conquest. The spirit is intrepid but also hardened by experience, skeptical about Alabama but hopeful of New Mexico, optimistic that somewhere in the distance, in the darkness, a hot meal and cool sheets await.