At the age of 25, Orson Welles made Citizen Kane, perhaps the greatest film of all time. He spent the next 45 years struggling, supporting himself with schlock acting roles, grubbing for financial backing and floundering. At the end of Welles's life, the writer Gore Vidal often invited him to his Los Angeles home. Welles always accepted, with delight. An hour before each party, Welles invariably phoned Vidal to beg out: "I have an early call tomorrow. For a commercial. Dog food, I think it is this time. No, I do not eat from the can on camera, but I celebrate the contents. Yes, I have fallen so low."

Today, Welles's "celebrations" might finally be paying off the way he had wanted. In the 1970s, Welles earned the contemporary equivalent of $75,000 a day for his commercial work, according to Josh Karp's new book, Orson Welles's Last Movie. Advertising contracts paid him as much as half a million dollars a year, plus residuals, Gary Graver wrote in his memoir, Making Movies With Orson Welles. Graver claims Welles didn't cut the ads for the money or because he was washed up. He says Welles was making a comfortable living at the time, owned two houses and "was proud that for the first time in his life he had Visa and MasterCards."

But Welles did need cash for his film projects. From 1970 until his death, he tried to finance The Other Side of the Wind, a comeback film about a director who needs backers to bankroll his comeback film. Today, three producers teamed up to launch an Indiegogo campaign in attempt to raise the final $2 million they say is needed to finish the movie, which they hope to complete by the end of the year. In addition to a "five-foot high" pile of original scripts, notes and memos, the producers behind the project found the 42-minute work print of the film that Welles had "smuggled out of France," producer Filip Jan Rymsza told The Hollywood Reporter. Rymsza said the producers are using the cut "as a blueprint for the remainder, some of which is in an assembly state." The campaign will be up until June 14. Contributors can receive hand-painted vintage posters, Wellesian-style terry cloth bathrobes, tickets to the film premiere and original film canisters.

If crowdfunding had existed in the mid-20th century, Welles's career might have taken a different turn. "Orson would not have had the problems he did," said Rymsza. "He was always trying to keep control."

Welles died in 1985 at the age of 70. This week would have marked his 100th birthday. To commemorate his centenary, I've archived his late-career slumming that he used to finance his final film. (Welles raised $750,000 of his own money for The Other Side of the Wind.)

1969: Eastern Airlines

In his memoir Making Movies With Orson Welles, Gary Graver recalls that Welles referred to his commercials as "working in the suburbs of cinema." But Welles didn't mind the work. His deep, booming voice lent itself to ads and narration. Welles hated working in giant recording studios, though. He had his own recording equipment, and hired Graver to be his engineer. Welles was in Spain when Eastern Airlines hired him for its "Wings of Man" campaign. He elected to film the shoot in the middle of farmland, thinking the setting would be quiet and that "no one will ever know." But Eastern knew. The airline telegrammed Welles three days later: "We like the voice work very much. But we can hear cows and pigs and chickens in the background. Orson, could you please do this again?"

1970: Findus Frozen Peas

Welles recorded a series of spots for British TV in which he shilled peas for the Swedish frozen food brand Findus. "He did quite a few jobs purely for the money he could get as an actor and couldn't get as a director," wrote Peter Bogdanovich. "One of the supreme ironies of American film: Orson Welles couldn't get financed. So he used his acting (and commercials) money to finance his directing." The British Film Institute lists four Findus ads that seem to feature Welles voiceovers: "France," "Highlands," "Normandy" and "Shetland." But the blooper reel—sometimes called "In July" or "Yes, Always"—of Welles complaining to the producer went viral long ago.

Nineties kids will remember Welles's Frozen Peas commercial from the cartoon series, Animaniacs. It featured an almost word-for-word parody with Pinky and the Brain (the Brain played Welles). The off-color language was replaced for the TV cartoon version, with lines like "I'll make cheese for you" instead of "I'll go down on you."

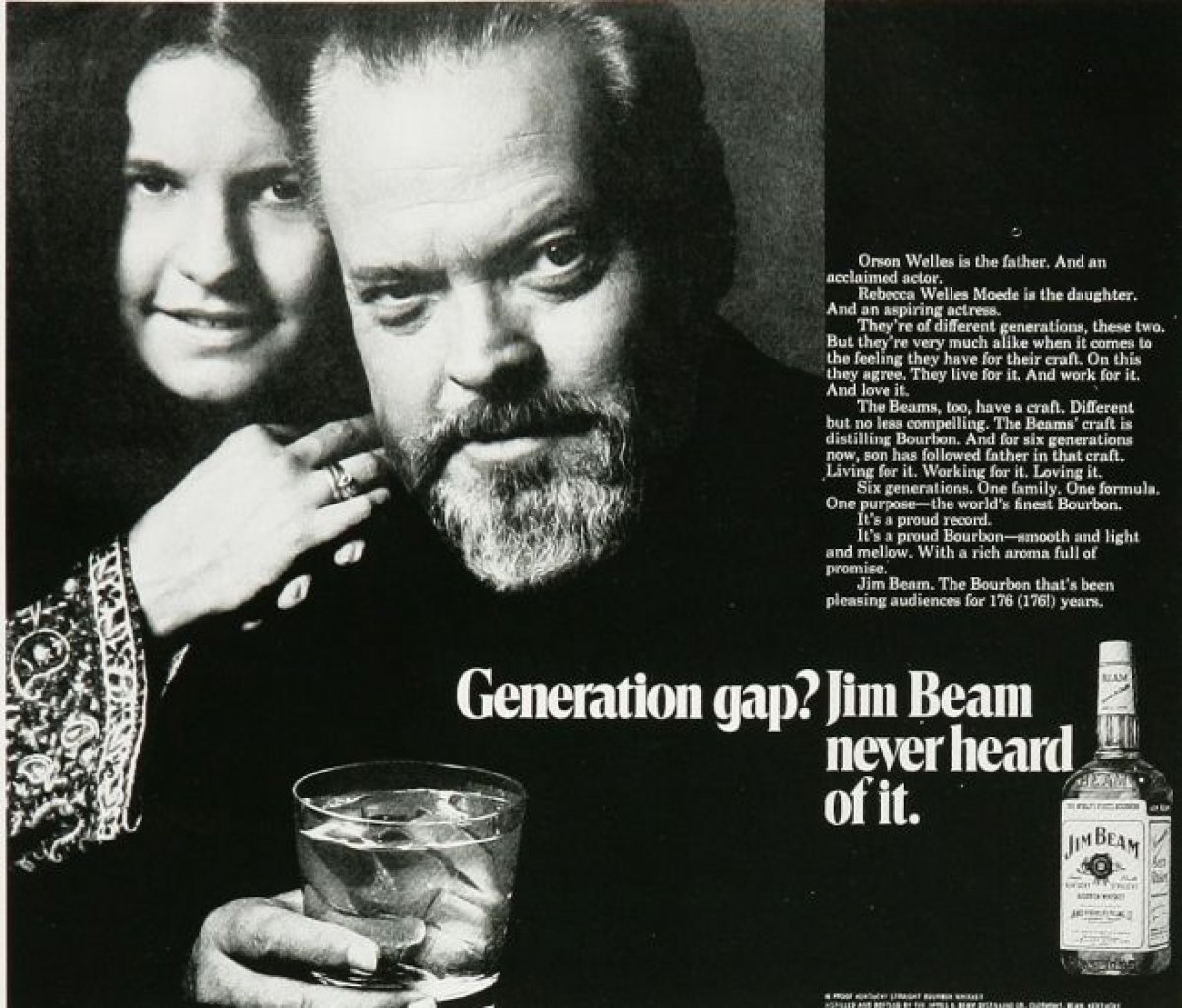

1972: Jim Beam

Welles posed with daughter Rebecca Welles Moede for a series of Jim Beam ads. Welles called his stints as a pitchman "the most innocent form of whoring I know."

1975: Carlsberg

"Probably the best lager in the world" was at one time being sold by probably the best director in the world. "Don't worry about money on your way up," Welles once told actress Geraldine Fitzgerald. "No one makes money on their way up. All the money is made coming down."

1975: Domecq Sherry

In his 1966 film Chimes at Midnight, Welles plays Falstaff and recites a Shakespearean speech in praise of sherry. Nine years later, the house of Domecq hired him for a series of British TV adverts. The commercials were shot at the Magic Castle in downtown Hollywood, where Welles also filmed The Orson Welles Magic Show. The success of these promotions begat Welles's now infamous Paul Masson wine ads.

1978-1980: Paul Masson Wine

For three years Welles was the face of Paul Masson wine, and the resulting commercials are worthy of their cult status. "We will sell no wine before its time" is the slogan Welles repeats. Here are a few of the vintages he pitched:

Champagne (1978)

Emerald Dry (1979)

Burgundy (1980)

Welles and Masson weren't exactly drinking buddies. "I have never seen more seedier, about-to-be-fired sad sacks than were responsible for those Paul Masson ads," Welles told Henry Jaglom in Lunches With Orson Welles. "The agency hated me because I kept trying to improve their copy." Graver confirms Welles's conflicts: "He would argue with people. He'd get a text and look at me and say, 'They're not gonna have me say this, that this wine is finer than a Stradivarius!' So he didn't."

Welles's most popular Paul Masson spots aren't the ads but the drunken outtakes.

His busking for Paul Masson ended after he told a talk show host that he was dieting and never actually drank the wine. Paul Masson dropped Welles, replacing him with John Gielgud to push its line of light wines.

1978: Vivitar Compact Camera

Welles praises the camera's built-in electronic flash: "Now my flash pictures don't have to be blurry or fuzzy because somebody moved." If only he'd had one while filming the three-and-a-half-minute crane shot that ends in an explosion at the beginning of Touch of Evil.

1978: Caesars Guide to Gaming With Orson Welles

A short film by Caesars Palace Casino in which Welles gives betting and gaming tips. He proclaims: "I've been asked by Caesars Palace to tell you a little about gaming. I guess they've asked me because I know a little about cards, a little about history and, well, because I've been known to take a long shot or two." He hams up his counsel with tales of Ancient Greece and the bone-tossing contests of primitive man.

1979: G&G Nikka Japanese Whiskey

This commercial played overseas, but the company didn't follow through with the not-airing-after-a-certain-time part of the contract. Welles told Jaglom that the spot cost him a five-year French cognac contract when the owner of the company caught it on the TV in his Hong Kong hotel room.

1979: The Muppet Movie

Near the end of the film, the Muppets go to Hollywood and are hired by studio exec Lew Lord, played by Welles.

1979: Perrier

Welles bubbles in this French ad.

1981: Dark Tower board game

The geekiness of this commercial may have helped him land the role of narrator for the Revenge of the Nerds trailer three years later.

1982: Stove Top Stuffing

In perhaps the most pitch-perfect impersonation of Welles ever filmed, John Candy embodied the full-bodied auteur. The premise of this SCTV parody: At the end of an installment of The Merv Griffin Show, the Close Encounters mothership arrives. Merv (Rick Moranis) and Steven Spielberg (Dave Thomas), who's directing bonus footage, enter the craft to meet the crew filming The Making of Merv: The Special Edition. Guests include Welles, George Lucas (Eugene Levy) and HAL the Computer from 2001: A Space Odyssey. At one point, Welles molds a scale model of Devils Tower out of Stove Top stuffing.

1984: Revenge of the Nerds

Welles narrated the trailer of the dweeb classic.

1985: Nashua Photocopiers

Welles quoted Shakespeare and explains the "dependability" of an off-brand Xerox machine.

1986: The Transformers: The Movie

Welles was the voice of the Unicron, an enormous robot that eats planets.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Gogo Lidz was 19 when her first feature story was published in the Los Angeles Times in 2004. She wrote freelance for ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.