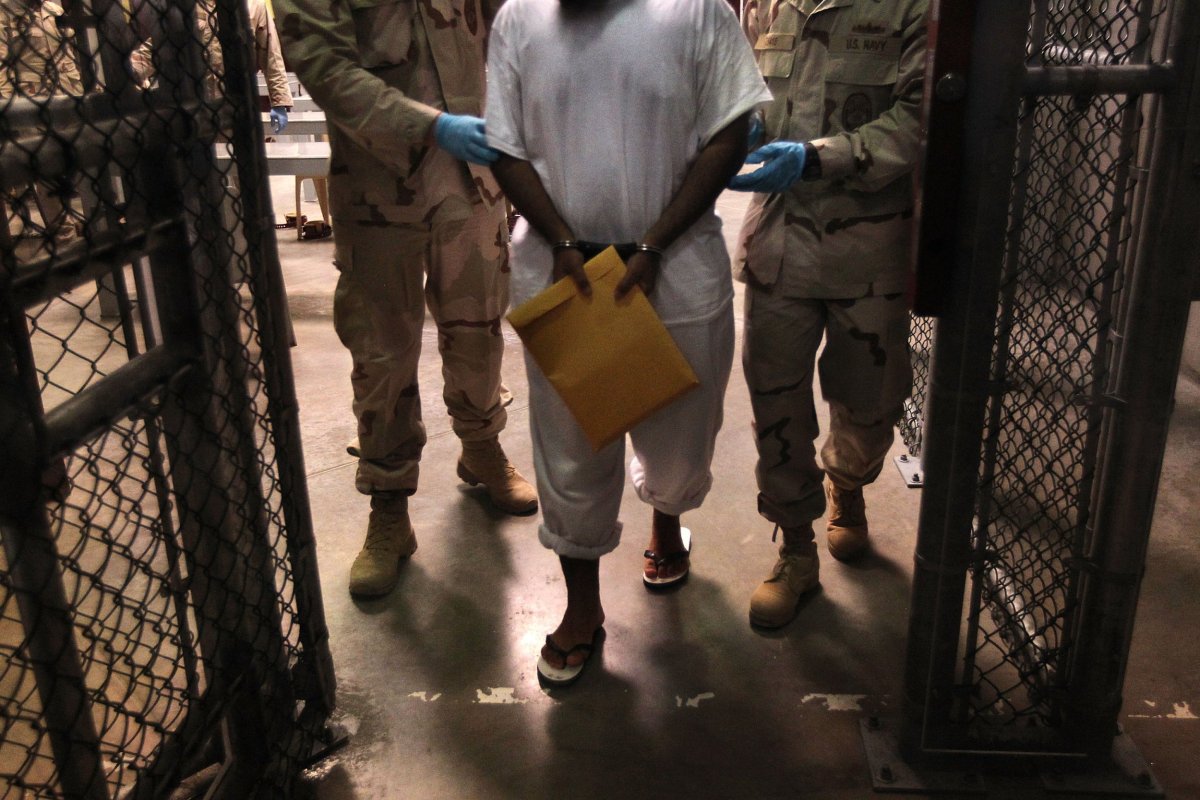

On October 15, 2017, 25 guards rushed into Saifullah Paracha's cell, one holding a video camera. They forced him onto his stomach before strapping him to a stretcher. He was handcuffed, hoisted out of the lock-up and taken to a cell in solitary confinement.

At 70, Paracha is Guantanamo Bay's oldest prisoner. A former businessman from Pakistan, he is accused by the U.S. authorities of helping Al-Qaeda and has been detained at the U.S.-run camp in southeast Cuba for 13 years.

After his "force cell extraction" by guards, Paracha said he languished alone in a cell for three days. It was the first time he had received this kind of treatment in over a decade.

Paracha believes the harsh treatment is a direct result of the changing of the guard in Washington, and the election of Donald Trump as president. The U.S. military base was converted into a detention center under the administration of George W. Bush in 2002 to hold terrorism suspects captured during the war in Afghanistan, and later Iraq. Two years later, on September 19, 2004, Paracha arrived at Guantanamo.

At its peak, Guatanamo was home to 684 prisoners, many captured in Iraq and Afghanistan, but others picked up by local or U.S. authorities elsewhere in Asia and Africa. Under Bush and later President Barack Obama, all but a handful of prisoners were either transfered home or moved to other countries. But Obama never managed to end operations at the controversial prison despite making its closure one of his key election promises.

President Trump has not made any moves toward closing the camp, despite continued criticisms from human rights advocates and sustained anti-U.S. sentiment among Muslims across the world.

Currently only 41 men remain at Guantanamo and as many as six of them are on hunger strike in protest at their many years of incarceration without charge. Paracha says that it is because of this that prisoners are being subject to collective punishment and increasingly harsh treatment by guards.

He claims that under the new administration, military officials are allowing hunger-strikers to weaken past the point of medical intervention, when prisoners were previously subjected to the force-feeding of nutritional supplements through nasogastic tubes, pushed through their noses and into their stomachs. Detainees have accused officials of allowing them to waste away to the point of near-death.

As the hunger strikers' treatment worsened, Paracha—who says he has never participated in a hunger strike because of his age—made a stand, writing a letter to the commander of the facility about their mistreatment. Thirty minutes after sending it, the guards rushed into his cell and took him to solitary confinement.

"We are getting collective punishment because of the hunger strike," he told Newsweek via his lawyer. (Inmates are rarely allowed visitors and cannot speak to the press.) "It felt like when we were brought in to Gitmo. Not since the beginning days of Guantanamo has it been like this. It's a hell."

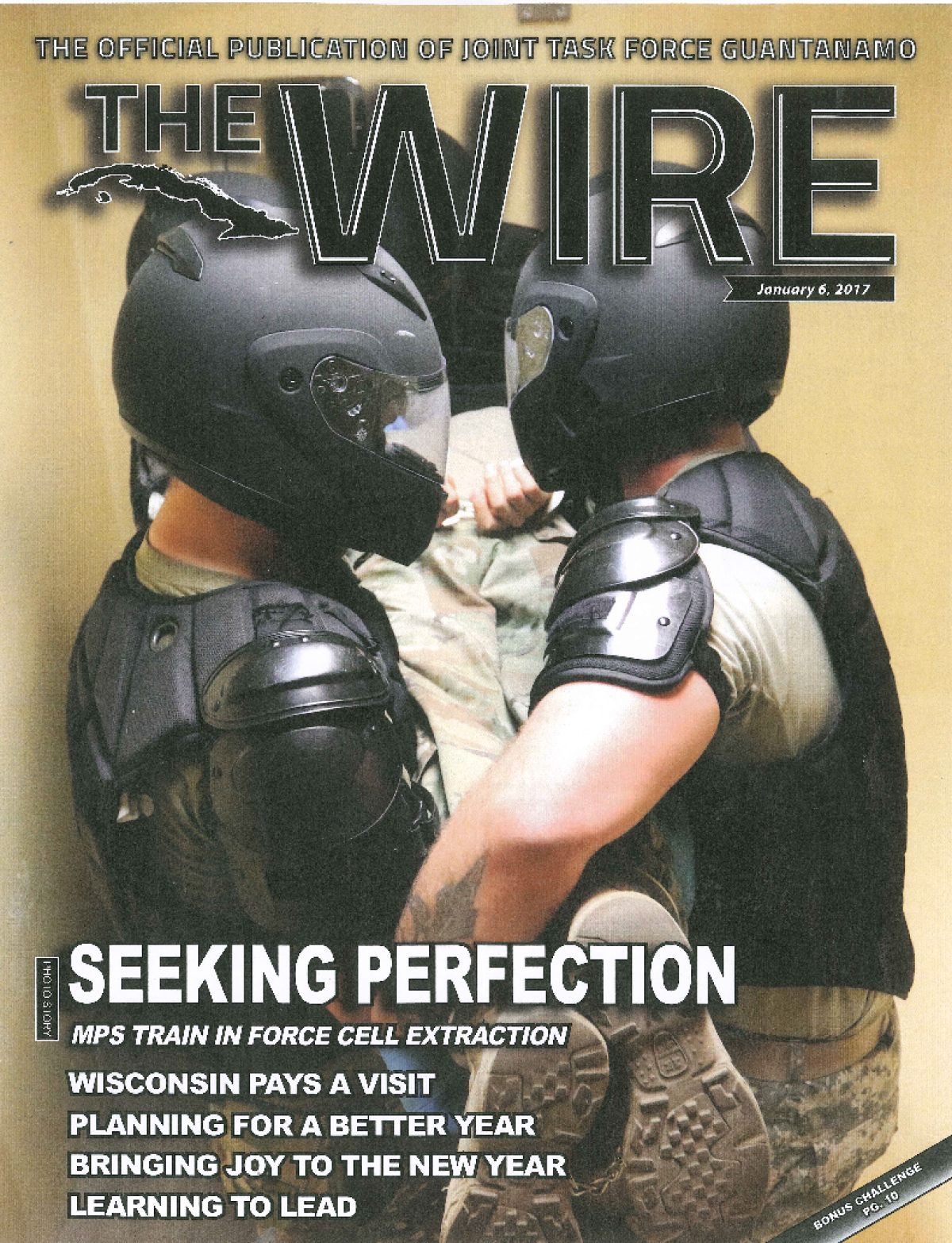

The January issue of Guantanamo's infamous newsletter The Wire contained a feature story on force cell extractions, with the cover photograph revealing the body armor worn by guards during the processes. Such extractions are often violent and have resulted in broken bones, concussions and even deaths of prisoners at both Guantanamo and facilities across the U.S. Prisoners are often kept in the dark about their selection for extraction.

"I've always been observing the camp rules," Paracha says. "I've never been disciplined. I've never been told that I broke any of the rules."

The Pentagon would not comment on Paracha's claims about his treatment, but said it makes efforts to meet standards of international law at the detention center.

"As a matter of policy, we do not comment on individual detainee matters," Heather Babb, Department of Defense spokeswomen, said in an email statement. "The Department of Defense is committed to treating all detainees humanely, and in accordance with all applicable domestic law and policy and international obligations, including Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions."

Paracha lived in the U.S. for more than a decade, studying computer systems analysis at the New York Institute of Technology, and eventually became a permanent resident. After moving back to Pakistan in the mid-1980s, he set up several charities and a television production company through which he attempted to arrange an interview with Osama bin Laden.

But Washington accused him and his son, Uzair, who is serving a 30-year prison sentence in a mainland facility for aiding a terrorist organization, of trying to help a suspected Al-Qaeda member into the country. It also said he had researched explosives and made suggestions to members of Al-Qaeda about how they could smuggle them into the U.S.

Paracha denies any knowledge of Al-Qaeda plots.

He was captured in the Thai capital, Bangkok, on July 8, 2003, after the FBI arranged for his arrest in an elaborate sting to meet some buyers. He was then flown to the U.S.-run prison Bagram in Afghanistan. He was held there for a year, during which time he claims he was tortured, before being flown to Guantanamo.

U.S. authorities allege that he had personally met with bin Laden, the former Al-Qaeda leader and mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, and worked with the group's external operations chief Khalid Sheikh Mohammed on finances and propaganda for Al-Qaeda. The Pentagon said that he made bin Laden several business propositions. As recently as 2010, it graded Paracha a "high risk" to U.S. national security.

In May, the Guantanamo parole board rejected Paracha's offer to close his businesses upon release from the compound as evidence that he had no ill intent toward U.S. citizens or desire to fund extremist groups.

The board said he would remain in detention for his "continued refusal to take responsibility for his involvement with Al-Qaeda" and lack of remorse for prior actions. But his representation has always argued that he cannot show remorse for activities that he is adamant he never participated in.

Shelby Sullivan-Bennis, Paracha's lawyer at the international human rights organization Reprieve, called on the U.S. authorities to end Paracha's ordeal and demands a fair trial for the father-of-four.

"My 70-year-old client Saifullah is aging and sick," Sullivan-Bennis tells Newsweek. "When I heard that he had been dragged from his cell and thrown into solitary confinement for the first time ever, I knew the new crackdown at Gitmo had reached fever pitch."

She adds: "After 13 years of detention without charge, and two heart attacks, Saifullah needs to be tried or released. It is downright barbaric that instead, he is facing physical abuse and the anguish of solitary confinement."

Paracha's concerns are less about his own health—despite a long list of ailments such as gout, coronary artery disease and diverticulosis—but the wider treatment of the few dozen prisoners remaining at the camp, which has long out-lived its own projected life-span.

Trump, rather than showing signs of shutting down the prison camp, has suggested that he would expand the number of individuals held at the facility, referring to them as "bad dudes," and saying he would be "keeping open" the facility. With at least three more years of the Trump administration remaining, hope for Paracha and his fellow inmates is in low reserve.

"They are just humiliating us and punishing everyone," he says. "The policies are getting worse."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jack is International Security and Terrorism Correspondent for Newsweek.

Email: j.moore@newsweek.com

Encrypted email: jfxm@protonmail.com

Available on Whatsapp, Signal, Wickr, Telegram, Viber.

Twitter: @JFXM

Instagram: Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.