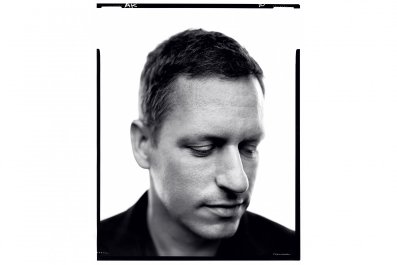

Fifteen years after she launched her career internationally with Bend It Like Beckham—the hit British comedy about a teenage Punjabi Sikh girl who dreams of being a football player—Gurinder Chadha is reinventing herself. She began by writing and directing a comedy in 1993 about a busload of British Indian women going on a daytrip to the seaside (Bhaji on the Beach), then moved on to a Bollywood take on a Jane Austen comedy (Bride and Prejudice, 2004). After that came a black comedy about a British Indian mother murdering her daughter's useless boyfriends with poisoned curries (It's a Wonderful Afterlife, 2010). Now she's finally playing it straight: Her latest film, Viceroy's House, is serious, personal, and a story she's wanted to tell for the better part of a decade.

"I was sat where you are, actually," she says, pointing to the sofa in her living room in Primrose Hill, an affluent part of northwest London. "It was seven or eight years ago. I was with a friend who said, 'It's your time now, Gurinder. You've done great comedies, but you're here to do something much bigger.' As she said it, I realized, 'I have to do something on Partition.'"

The release of Viceroy's House is timed to coincide with the 70th anniversary of the partition of British India into Muslim-majority Pakistan and Hindu-majority India. Hugh Bonneville plays Lord Louis Mountbatten, the last viceroy of India, who oversaw British India's transition into two independent states, a task made more complicated by violent clashes between India's Hindu and Muslim populations.

Gillian Anderson plays his wife, portrayed in the film as a benevolent woman who develops a close bond with her Indian servants. As Partition rumors spread, the servants eavesdrop on arguments between political leaders in the viceroy's drawing rooms—and have their own disagreements about their country's future. Meanwhile, a romance between a Hindu valet (Manish Dayal) and a Muslim translator, Aalia (Huma Qureshi), acts as a metaphor for the political tensions outside.

Partition reverberated through Chadha's own home life, affecting her grandparents on both sides of the family. In 1947, her paternal grandfather, a Sikh, was living and working in Kenya, where he had a business; his wife and their four youngest children had remained in Punjab. Partition turned them into refugees. Like 15 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims, the Chadha family were forced to leave their home—which in their case was now in Muslim-majority Pakistan.

During the journey to India, the couple's youngest daughter died from starvation, one of more than a million people who lost their lives in the upheaval. The family spent 18 months in a refugee camp before Chadha's grandfather found them. Viceroy's House ends with a dedication to the little girl who died, an aunt Chadha never met. For the director, she represents all the women who faced hardship during Partition. "Filmmakers don't often get a chance to say, so clearly, 'This is why I made this film,'" she says.

Her maternal grandmother also suffered, traveling from Pakistan to India as a post-Partition refugee. Chadha was born in Kenya; at the age of 2 she moved with her parents to Southall, in west London, where her grandmother duly joined them. Chadha grew up seeing the effects of her psychological wounds. "She was quite traumatized," she says. "She'd get quite agitated when something violent happened on telly or whenever a baddie came on. We would laugh at her because we were children, but that trauma had an effect on me. Years later, when I did my episode of [the BBC genealogy series] Who Do You Think You Are? [in 2006], I went to Pakistan, to my ancestral homeland for the first time. I started thinking about my personal history."

Her hope is that the film will help people who are still affected by the legacy of Partition and ongoing tensions between India and Pakistan—which often erupt in violence in the contested border area of Kashmir. Chadha is well aware of the politically sensitive relationship between the two countries and was careful not to portray any one side—the Hindus, Muslims or the British—as villains in the movie. "The vision was to make a film I could watch in Lahore, London and Delhi. You can't tell who's Muslim or Hindu," she says. "I made the costumes generic in some ways. I didn't show violence specifically against one group or another. I wanted to make a film where you ask at the end, What was the point of the violence? It didn't matter who was the victim of it, who perpetrated it—everyone was the victim."

Viceroy's House is Chadha's first feature film in seven years. Even after the success of Bend It Like Beckham, which cost £3.5 million ($4.4 million) to make and grossed £61 million ($76 million) globally, it seems that financing stories about minorities remains a challenge. "As soon as you say you want to make a film and it's got an Asian person as a protagonist, forget it. You're in for a struggle," she says. People in the industry and beyond now pay more attention to the lack of diversity in British and American films, but Chadha says the issue has existed since she made Bhaji on the Beach. "I was the first Asian woman to make a feature film in Britain. And 25 years later, I'm still [the only one]."

Would life be easier if she were a white, male director? "I don't really like questions like that because they're too reductionist," she says. "If I wanted to make films white men make, I could quite easily make rom-coms which have no cultural angle at all. And it would be easier for me [to get films made]."

Like the characters crusading for independence in Viceroy's House, Chadha intends to continue challenging the established order of things. "I've proved you can put people of color in films that do make money," she says. "Yes, I've got to work harder, but I'm prepared to do it."

Viceroy's House is out now.