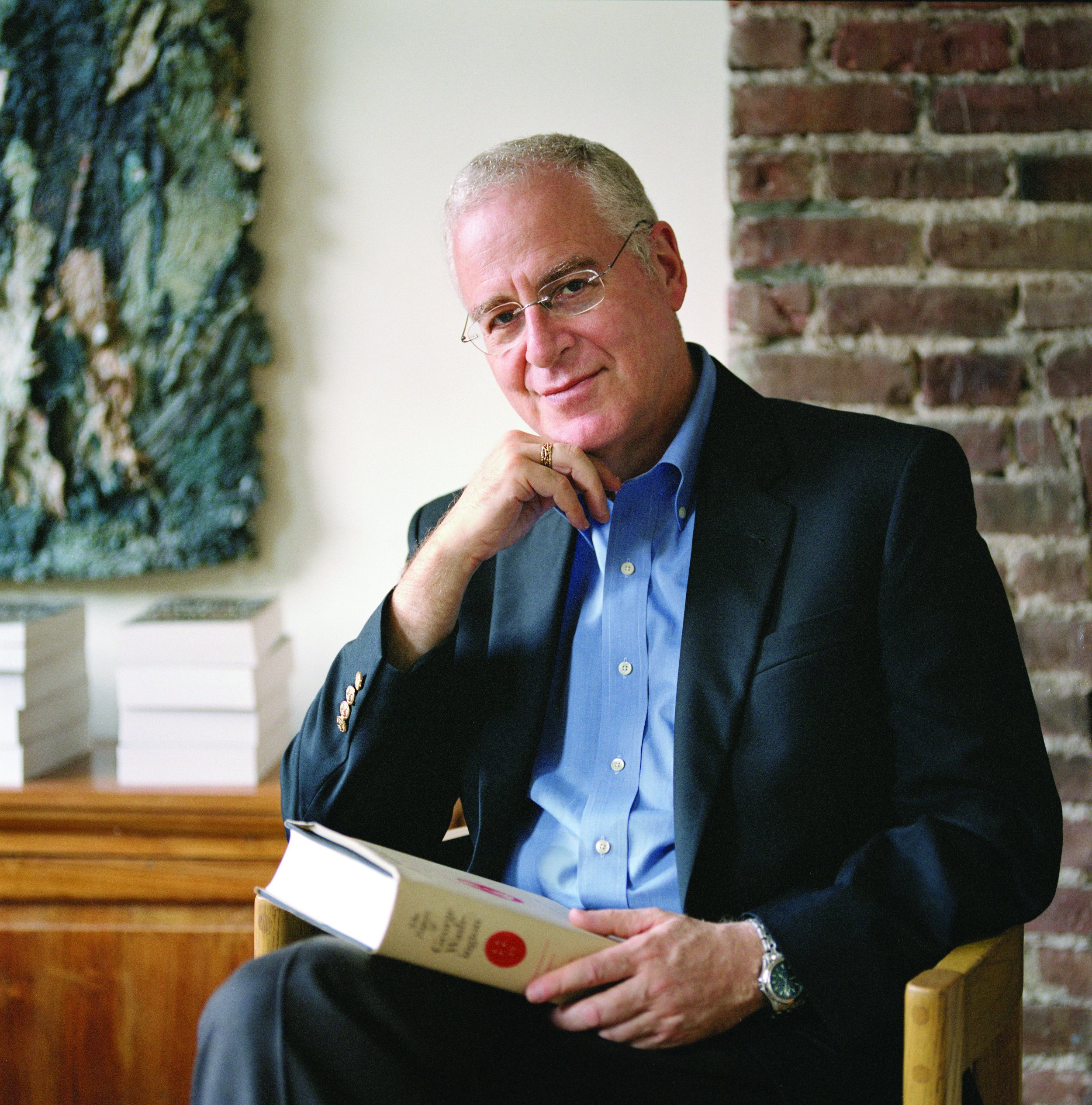

Ron Chernow, who wrote the biography that inspired 'Hamilton,' is both a historical consultant on the show and one of its biggest fans. This interview, by Senior Editor Tim Baker, and other articles about the Broadway phenomenon are featured in Newsweek's Special Edition, Hamilton.

When did you first hear someone was going to make a hip-hop musical out of your biography of Hamilton?

Back in the fall of 2008, I ran into a friend in the neighborhood whose daughter had gone to Wesleyan with Lin-Manuel Miranda. He started by telling me "This hip-hop artist," as he referred to Lin, had read my Hamilton book; it made this enormous impression, and he was excited to fi nd out that he could meet me through these friends.

This would have been during In The Heights?

In fact it was at the same theater, the Richard Rodgers, where Hamilton is. I went to a Sunday matinee and then went backstage, and Lin started telling me he wanted to do either a concept album about the life of Alexander Hamilton or, if all went according to plan, it would be his second musical. He said he had been reading the book on vacation in Mexico, and hip-hop songs had started rising off the page. I could tell from that very first conversation with Lin that he wanted to do a very serious, dramatic rendering. If he had wanted to do a parody or something, I wouldn't have gone along with it. But I could see he really wanted to capture Hamilton in the way I had in the book, but knowing nothing about hip-hop I said: "Should hip-hop be the vehicle for telling this kind of story?"

What was his response?

He said to me: "Ron, I'm going to educate you about hip-hop." And he pointed out a number of features about hip-hop that are still very relevant to the show, the fi rst of which was that you can pack more information into hip-hop lyrics than any other musical form because the lyrics are very dense and very rapid. He explained about all the wordplay and internal rhymes and rhyme endings. I may have been skeptical at fi rst, but I was charmed by Lin. I had been a fan of In the Heights and was intrigued by what he was saying. He very quickly made a believer out of me.

If you can think back to the fi rst time or the first rehearsal you heard Lin-Manuel put this story to music, was it an immediate conversion experience, or had he convinced you before that?

Well, I can talk about a couple of moments. After he had fi nished writing the fi rst song, which he spent an entire year writing—I think he was already writing it when I met him—he came over to my apartment in Brooklyn Heights and sat on my living room sofa and started to snap his fi ngers and sing what is still the fi rst song. It's almost verbatim the same song. When he finished, he said "What do you think?" And I said, "I think it's the most amazing thing I've ever heard." He had packed the first 40 pages of my book into this 4.5-minute song and had done so very accurately. Then he spent a year on the second song. I think that those were the two breakthrough songs that convinced him and certainly convinced me he would be able to do it.

How did that year/song pace pick up?

We said at this rate we would all be dead by the time Lin finished, so Thomas [Kail] put him on a diet of I think two songs a month. And when Lin wrote the songs, he would send them to me over the internet, so I was getting the show piecemeal, one or two songs at a time. Then there came a day, probably three or four years ago now, where he told me for the first time he was working with actors.

What were your first impressions of seeing these scenes played out by real people?

I remember going up there mid-afternoon one weekday and opening the door, and there were eight actors standing in front of eight music stands and my first thought was, "Oh my God, they're all black and Latino." I really had not given much thought to the casting, but, you know, for someone of my generation, a show on the founding fathers meant something like 1776—a bunch of middle-aged white guys with wigs and buckled shoes. I was immediately captivated by Lin's casting. They had beautiful voices, and they seemed to have a special passion and feel for this musical. But it was also so daring and revolutionary to cast these parts with the very people who were excluded during this period from American history.

Once you saw the fully fleshed-out characters as Lin had written them, was there any sort of fresh perspective that came to the historical figures in your mind?

This was very interesting to me. I was very struck by the fact that Lin had presented Hamilton as this very intense, driven and almost frenetic character. And I was a little bit thrown when I first saw this, but then I said to myself, "You know, this is really very ingenious" because I described Hamilton in the book as a whirlwind of energy. In fact, when it was reviewed by Edmund Morgan in the New York Review of Books, the title of the review was "The Whirlwind." Lin had given the idea a perfect visual expression. From the very opening number, Hamilton is dashing around the stage, and he's reading books, and he's packing bags and he's just a perpetual motion machine.

As you studied Hamilton, did it make sense to you that he would meet his end in an "affair of honor?"

Hamilton was extremely combative. Not only was he combative, but he also overreacted to anything he perceived as a threat or a criticism. I think that because he had been an illegitimate, orphan kid on the streets of St. Croix, this was a survival mechanism for someone who must've felt so powerless that when attacked, he would respond with all the ammunition at his disposal. He would really overreact to things, and the overreaction would get him into even more trouble. He always felt he had to bury his opponents and really never [learned] that there are moments in life where less is more.

That combativeness definitely comes out in the show, but so does Hamilton's extreme personability and geniality.

That was a very good point to raise. Hamilton had a certain social versatility, and in a way that is understandable because he's someone who rises up from the lowest rungs of society and then scales the top. And he gets to know people from every strata along the way. His fi rst and closest friend during the war, Hercules Mulligan, was a tailor and more like the people Hamilton would have met in St. Croix— tradespeople. But then this same person is friends with Lafayette, who had been invited often to the court of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, and John Laurens, whose father is one of the richest men in South Carolina. What makes the Maria Reynolds scandal so interesting is that you feel the Reynolds couple are kind of like characters out of Hamilton's past. They're not from this fancy world that he has risen into but he probably knew a lot of characters like them back in St. Croix.

How real was the idea of legacy to the founders? Is this more of a dramatic device, or does Hamilton's concern for his legacy in the show refl ect a historical truth?

The thing with all the Founding Fathers, one of the most common words they used was posterity. They were constantly referring to posterity. In 1781, George Washington got an appropriation from Congress to produce a beautiful edition of his wartime papers. He had as many as six clerks working full-time to produce these beautiful volumes of his wartime papers, and by the time he got back to Mount Vernon there were 28 volumes. He wrote to Richard Varick, who helped compile them: "I'm truly convinced that neither the present age or posterity will consider the time and labor which have been employed in accomplishing [this task]." Washington is explicitly talking about the fact that he went through this not just for his own age.

This was a task that, for Hamilton, was largely left to his widow, Eliza?

She sent questionnaires to all the people who knew Alexander, asking for their recollections. She went to Mount Vernon to secure the copies of the letters Hamilton wrote to Washington. She tried desperately to find a biographer, and several people said they'd do it but then didn't. She finally had a son, John Church Hamilton, write a very hagiographic biography. I certainly feel very indebted to Elizabeth Schuyler Hamilton for having done that. The only thing that's frustrating about her: She spent all this time trying to preserve her husband's legacy she failed to give us the one thing that we most wanted from her, which is her own memoir.

Having seen the show with a historian's perspective, what do you think some future chronicler of Broadway is going to say about Hamilton?

My guess is 25, 50, 100 years from now, people will be concerned with not only the way we perceived and portray these fi gures of the founding era but also what it says about our own time, because this is a show that straddles two worlds. You walk into the theater, and there are all these fi gures from the 18th century. But at the same time, they're also recognizably fi gures of the 21st century. In fact, one of the ingenious things that Tommy Kail did was coming up with this idea that everyone onstage would be 18th-century from the neck down and 21st century from the neck up. I think that they'll be talking about, among other things, the changing demographics of the country—the fact that this came out at the point where more than 40 percent of the births in America are identifi ed as African-American, Asian-American, Latino or biracial. We're seeing the same thing in American politics. You have one side of the aisle celebrating these changes and the other side of the aisle dismayed by all these changes. That will be a huge part of what critics and historians look at.

So, when you're sitting in the audience at Hamilton 1, do you have a favorite moment as an audience member?

Oh, absolutely, yeah. My favorite song and my favorite scene is "Satisfied." Lin often says Angelica is the smartest woman on the stage, maybe the smartest person on the stage, and so he wanted to show this explosive intelligence Angelica has. It's really quite dazzling and fantastically well-written. I just enjoy the character of Angelica, and of course Renée has been so extraordinary in doing it.

Is there another moment that hits you as a historian?

I always find it thrilling to watch the Yorktown scene because it captures the pride and the joy of the victory there, the way they jump up on their little soap boxes and they're beating their chests and they're saying "We won! We won!" The audience always just spontaneously bursts into applause. But there are a lot of moments—I never tire of watching the show.

1 Chernow has seen the show dozens of times, always paying for his own ticket despite his status as a historical advisor to the production.

This article was excerpted from Newsweek's Special Edition, Hamilton, by Senior Editor Tim Baker. For a backstage pass to the Broadway musical sweeping the nation, pick up a copy today.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.