It is a Muslim holiday in Durres, a dusty port town on the coast of Albania. Shops are shut, blinds drawn down and the streets look all but deserted. On the outskirts, cars stuffed with entire families – mum dad, gran, gramps and the kids – head in convoy towards a strip of restaurants strung out along the Adriatic coast, to tuck into platters of local seafish, prawns and salad. A generation ago, marking Eid, or any other Muslim or Christian holiday, would have been a high-risk gesture in Albania. Its notoriously unforgiving Communist regime did not take a dim view of religion but outlawed it completely. Today, religion in Albania is back, but not with a vengeance. The great religious holidays – which in this country tend first and foremost to mean Muslim holidays – are widely observed, but mostly as family affairs.

Albania is unique – the only overwhelmingly Muslim country in the whole of Europe. But the paradox is that in the centre of the capital, Tirana, not a headscarf is to be seen, let alone a burqa. A Muslim city in purely numerical terms, it is a hard-line Muslim's nightmare in most other senses. Women wear what they want and go and do as they please.

In the aftermath of the Paris killings, and the gloom they have cast over Europe's future relationship to Islam, the tolerant religious climate in Albania is drawing interest. To Pope Francis, this slip of a country in Europe's forgotten southeast is a sign that "a culture of encounter is possible". Addressing diplomats at the Vatican after the Paris killings, he lavished praise on the country he had visited the previous September, where he found relatively small Catholic and Orthodox Christian communities, plus a tiny congregation of Jews, co-existing happily with a far larger Muslim presence. Life in Albania, the Pontiff observed, was "marked by the peaceful coexistence and collaboration that exists among the followers of different religions in an atmosphere of respect and mutual trust".

Albanians are half-flattered and half-amused by their country's newfound reputation as one of the few places where different faiths get along. Tucking into his Eid lunch in Durres, one of my dining companions said Albanians were not actively tolerant so much as indifferent when it came to faith. Christianity, Islam and then atheism had all been forced on Albanians, he continued, and the legacy was a feeling of skepticism towards all dogmatic creeds.

Besar Likmeta, a journalist in Tirana, who follows religious affairs, says the failure of hard-line Islamists to recruit much of a following in Albania has much to do with the nation's "foundation myth". Albanians believe their country "was taken away from Europe and plunged into darkness by the Ottoman Empire – and that Islam was associated with that", he says. One result, even among believing Muslims, is a deep-rooted Occidentalism that the Communist experience did little to alter: "For 50 years we were completely isolated and dreaming of coca cola! We don't look East for answers but West. There has always been a feeling that we need to return to where we belong."

Likmeta says Islam undoubtedly revived in the chaos that followed the fall of Communism, while some Arab-based charities made headway in the turbulent 1990s among the dispossessed. But, such advances run up against a flinty pride in national identity. "We have 'Islam-lite'," he says. "People like Eid, and some go to the mosque on Friday, but things like wearing the hijab are perceived as things that do not belong to our culture".

Another major influence on the character of Islam in Albania is the strength of the mystical and pacific bektashi tradition. It is alsoseen as significant that the so-called "Gulenists", loyal to the US-based preacher Fetullah Gulen, are a force in the Albanian madrasas, as the movement stresses Islam's compatibility with science and democracy.

Jetta Xharra, an Albanian from neighbouring Kosovo, says Albanians on her side of the border see things in the same way. Her grandfather came from Albania to Kosovo after the Second World War and became an activist in a campaign launched by the new Communist authorities to get Muslim women to take off their veils. "He went from village to village to convince heads that it was right for women to remove the veils, and he didn't meet much resistance," she recalls. "People felt religion was something that had divided Albanians and prevented them from having a homeland." That sentiment hasn't changed in the intervening years, Xharra said: "Albanians in Kosovo feel more European than they do Islamic."

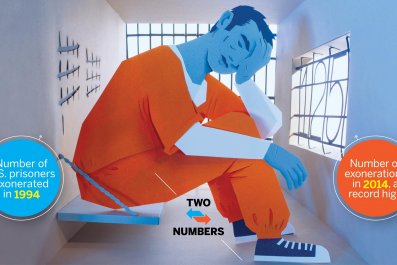

Some Albanian Muslims have embraced a more hard-core version of Islam recently, even if they're not that visible in the big cities. People in Albania and Kosovo were startled last year to read that up to 300 Albanians had gone to the Middle East to fight for ISIL militants. The fighters set up a special Facebook page, lauding the feats of Albanians in battle, which has since been taken down. The Kosovo authorities arrested around 40 people last year, including several imams, accusing them of joining the fight in the Middle East, or of recruiting others for jihad.

Gjeraqina Tuhina, an Albanian journalist in Brussels, is worried. "The radicalization of some Albanian Muslims is already happening," she says, "although this refers more to Albanians living outside Albania – from Macedonia, southern Serbia and finally Kosovo." She blames poverty, poor education and, in Kosovo especially, a feeling of isolation from Europe. "It's worth saying that only small part of society is being radicalised, but they are very active, as you can see from their activity on social networks," she adds.

Xharra, who has studied the profiles of the suspected Islamists arrested in Kosovo, notes that most were unemployed young men from remote, impoverished communities. "The main draw for the 40 'terrorists' arrested last year for going to Syria seems to have been the 60 euros a day that they thought they would get if they fought for Isis," she says.

Whatever their motives, Islamists in Albania or Kosovo cannot count on any sympathy from the political establishment. When news broke of the Paris outrage, Kosovo's woman President Atifete Jahjaga, and Albania's Prime Minister, Edi Rama, both headed for France to join 40 or so other world leaders standing at the front of the "Unity" march of solidarity with the victims. Keen to show that almost all Albanians – whatever their religion – felt just as strongly as he did over this issue, Prime Minister Rama took two priests and two Muslim clerics with him. n

Marcus Tanner is the author of "Albania's Mountain Queen, Edith Durham and the Balkans"