Thomas Harte is a trainee orthopaedic surgeon who also knows what it's like to be on the business end of a scalpel – he's undergone three urology operations since October to fix a kidney ailment. As he recovered from those procedures, he realised he often couldn't tell if his post-op symptoms were normal or alarming – "and I'm a bloody surgeon who's pretty knowledgeable." Harte was able to call on med school friends, who are urologists, to allay his fears and answer his questions, but he knows that that's not an option for the vast majority of patients.

Luckily for them, however, Harte is also a budding entrepreneur and co-founder of FH Works, a startup that's developed an interactive, video-centric mobile healthcare app called My Recovery that would be prescribed to patients undergoing elective surgery. The app, which is currently programmed for knee surgeries, but can be tweaked to work for most elective procedures – would help patients prepare for their operation, to understand what to expect during and after their hospital stay, and to guide them through any necessary rehabilitative physiotherapy exercises individually tailored to their needs.

In February, Harte's company took a critical step toward bringing My Recovery to the market. It struck a deal with London's Wellington Hospital, the UK's largest independent hospital, to finance a pilot study of the app. Neil Buckley, Wellington CEO, says he's looked at other health apps, but My Recovery was the first he'd seen he felt was worth trialling. "This one comes from doctors, you can see the clinical relevance," Buckley says. "They've done it in a very neat way."

My Recovery is one of many up-and-coming health apps that could, by improving efficiency, cutting costs and improving patient outcomes, radically change how healthcare is delivered. Most, like My Recovery, are still in their beta stage, but there are growing expectations that properly vetted, sophisticated health apps – aimed not at consumers but medical providers – will soon become part and parcel of healthcare systems worldwide. "There is some emerging evidence" from studies and randomised clinical trails that apps can absolutely improve the delivery of healthcare, says Professor Jeremy Wyatt, a health informatics expert at the University of Leeds.

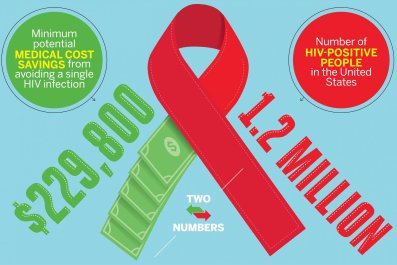

A 2012 report funded by the UK's National Health Service (NHS) claimed that digital technologies could help it save nearly £3bn a year in administrative costs, including £48m just by delivering pre-operative assessments remotely. A recent multi-university study found that each patient's face-to-face encounter with a healthcare provider costs £8.50, but drops to 15p when it's handled digitally.

As for improving care, a Leeds-led clinical study of a diet app called My Meal Mate found it helped patients lose more weight than those in a control grou, who charted their progress on paper or using online diaries. Apps that help improve medication compliance are seen as especially promising. The NHS estimates it spends more than £500m a year treating unnecessary ailments because of unused meds. So it's encouraging that a 2012 Australian clinical trial determined that adult diabetics using a self-management app had "significantly improved glycaemic control".

If My Recovery works as hoped, it could help reduce the amount of time patients need to stay in hospitals, and ultimately help them get the most out of their operations, because full recovery rates for orthopaedic surgeries are higher for patients who properly complete their physiotherapy exercise regimens. "It's about giving patients more control of the process," says Buckley, the Wellington CEO, "and that helps us manage the process better". It uses easy-to-understand graphics and videos to help patients prepare in advance for their forthcoming surgery and return home so they're more likely to be discharged from the hospital as quickly as possible. "Within the NHS, patients often stay in hospital too long, eating rubbish food and risking getting an infection," Harte says. "You are better off at home with the right care."

Ideally, patients who get replacement knees shouldn't stay in hospital more than three days, but most tend to remain hospitalised for five to seven days, often because they're ill-prepared to be discharged. Harte believes that most users of My Recovery will be able to go home after three days. Reducing admission times can, of course, be a huge money-saver.

Harte and his co-founder, Axel Sylvan, another 28-year-old surgeon, had initially planned to develop a physiotherapy app while they were students at the University of Manchester, after Sylvan had surgery on his spine. But their experiences as patients convinced them that while good physiotherapy was necessary, "it's a small problem compared to bad communication." Ill-informed patients can make poor decisions, which can cause them to needlessly seek unnecessary appointments or be readmitted into hospitals, further clogging an overloaded system.

The fact that apps like My Recovery would largely be prescribed by doctors should also allow them to stand apart in a crowded market. Already there are more than 100,000, mostly consumer-facing, health and fitness apps available for Apple and Android mobile operating systems, and thousands more are on the way. German consultants research2guidance predicts that the mobile health market will grow 61% by the end of 2017, to total revenues of $26bn, and that, by then, half of all smartphone users will have downloaded a health or fitness app.

Not all those thousands of consumer-oriented healthcare apps work as advertised or are safe. Anurag Gupta, an analyst at consulting firm Gartner, says that the accuracy of apps that diagnose ailments or monitor vital signs can range from a reassuring 98% to an alarming 6%. Wyatt agrees that "there are some bad apples."

One recent study found that apps for diagnosing melanomas were "atrociously inaccurate", Wyatt notes, while a Leeds study of apps that predict cardiovascular risk concluded they were "laughably bad". Despite those drawbacks and potential risks, there is no regulatory regime in the UK to control the sale of health apps. The NHS runs an online health apps library that rates apps as safe and trusted, but it was set up three years ago as a trial and is now woefully out of date.

"They are rebuilding it and will relaunch it by the end of this year," says Wyatt. But given that 10,000 to 20,000 health apps are released each year, it would be nearly impossible for any accrediting system to keep up that deluge, he adds. "That is a big concern."

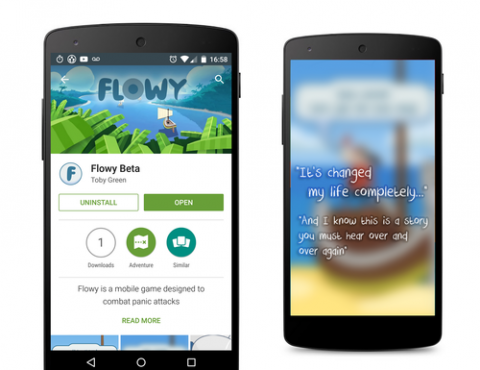

Clearly, no doctor or hospital will use or prescribe an app that hasn't been fully vetted. So serious developers are typically subjecting their prototypes to randomised clinical trials, even though they're not legally required to do so. "If you are creating an app for use by clinicians, you need to prove its efficacy," says Quynh Pham, lead researcher at Playlab. Playlab's launching Flowy, an app that uses games to help people manage panic attacks. It's already had one pilot trial, using 63 participants, that determined users showed a significant decline in symptoms compared to a control group.

Meanwhile, FaceTrack, an app that tracks how well patients suffering from facial paralysis – Bell's Palsy patients or stroke victims, for example – do their facial exercises, is set for clinical trials later this year, says Charles Nduka. He's the plastic surgeon who developed the app with Image Metrics, a British computer graphics company, whose software was used to reverse-age Brad Pitt in the movie The Curious Tale of Benjamin Button.

There are also concerns about how app developers handle sensitive data they might collect. Is it secure? Will it be sold for commercial purposes? Wyatt says patients that get apps prescribed by physicians or health systems can assume that their data is safe and not for sale. "We are very clear: data belongs to the patients. We can't sell it or pass it on," says Ali Parsa, CEO of Babylon Health, developer of a mobile app that allows patients to consult in real time with a General Practitioner or specialist via a video link for a fee. It's expected that the NHS will opt to bulk-buy the app to offer it to patients free of charge. Not only could the app help ease congestion at GP offices, but buying Babylon's services is cheaper for the NHS than having doctors seeing all their patients directly. Babylon had a low-key, soft rollout last May and fully launched last month.

A big indication that the NHS sees a bright future in apps: it's helped fund some of them. The Nominet Trust has paid £50,000, or 40%, of Flowy's development costs, and the Wellcome Trust is a co-funder of FaceTrack, to the tune of £110,000. Amazingly, however, in an environment where developers routinely spend tens of thousands of pounds on health apps, My Recovery so far hasn't had a penny of outside funding. Harte, Sylvan and John Banks, their CTO, have relied on their own pockets to cover costs.

The deal with Wellington Hospital not only injects FH Works with much needed financial help, it could also give it leverage to attract heavy-duty venture capital funding, enough to cover the cost of a clinical trial at an NHS hospital – which is what it will need to ensure the launch of My Recovery is a successful operation.