On Wednesday, astronomers announced that they had detected faint signals from what could be the very first stars in the universe, born just 180 million years after the Big Bang. The previous contenders formed more than twice as long after. That scientific journey required travels of a different kind: in order to actually spot the stars, the astronomers had to trek out to the middle of the Australian Outback.

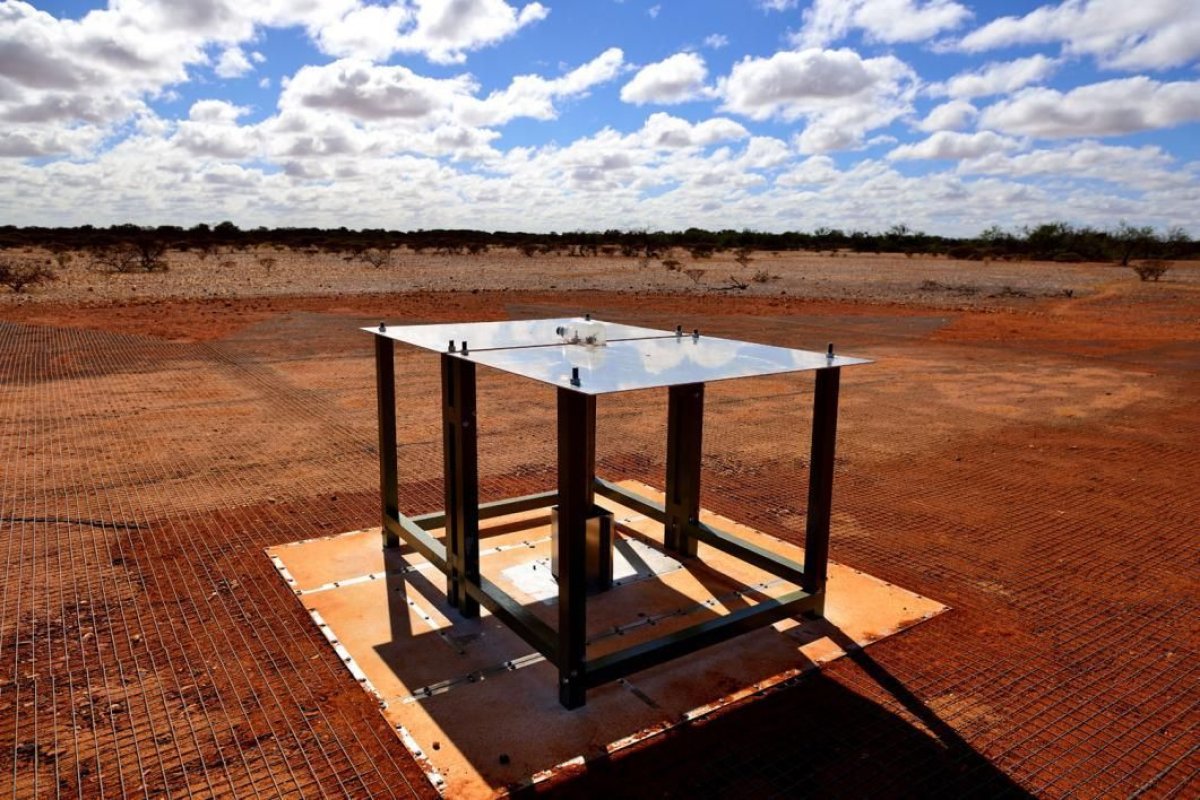

Specifically, they had to travel to the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory in Western Australia, a government-protected science site. The long commute was worth it, first author Judd Bowman, a cosmologist at Arizona State University, told Newsweek. "Really this was the best option in the world" for the project, he said. Once the team got there, they set up two incredibly sensitive detectors tuned to radio waves.

Radio waves are an invisible form of light with especially long wavelengths, which means they can travel vast distances, like across the universe. But there's one big problem with radio waves: We humans are awfully fond of them ourselves—they power a whole host of communications technology, including the radios they share a name with. "When you're driving in the car, you don't want to be changing the station all the time," Bowman said. Hence using a form of light that can travel with you.

But the radio waves Bowman and his colleagues wanted to hear are much fainter than radio waves produced here on Earth. That's why the Australian Outback was so appealing: Not only are there not many people nearby, but the government has banned FM radio broadcasts in the area.

Related: 3200 Phaethon: How the Still-Recovering Arecibo Telescope Saw This Asteroid Coming

Those broadcasts, it turns out, have exactly the same fingerprints as the signals the team was looking for. "It's amazingly quiet in this band," Bowman said of the Murchison area. And unlike other quiet places on the planet, because the site is home to other astronomical observatories, the area is equipped with everything else the scientists needed, like power generators and an Internet connection.

Before settling on Murchison, the team had also considered sites in Nevada and southeast Oregon, which Bowman said would have been the best American option. Another team looking for similar data to help confirm the new findings has settled on a different outpost, in the foothills of the Himalayas. That's truly the middle of nowhere, unlike the scientifically inclined Australian site.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Meghan Bartels is a science journalist based in New York City who covers the science happening on the surface of ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.