Hidden writing on 500-year-old parchments has uncovered fascinating new details about the first English expeditions to North America which set out from the port city of Bristol in the southwest of the U.K.

Nine years ago, Evan Jones, a historian from the University of Bristol, published a long-lost letter written by King Henry VII of England that detailed how William Weston, a Bristol merchant, was preparing an expedition to the "new found land" at the request of the monarch.

This expedition would take place in 1499, just a year after Christopher Columbus first landed on the South American mainland and two years after the Venetian explorer John Cabot reached North America in a ship, also commissioned by Henry VII, which left from Bristol.

Historians think that Weston's 1499 expedition was covered by the same royal patent issued to Cabot in 1496. However, many details of this period have long remained a mystery.

"[These early Bristol voyages] represented the first European exploration of North America since the Vikings reached there around 1000 A.D., yet we know so little about them," Jones told Newsweek. "So it's like having a great thousand-piece jigsaw puzzle, of which you only have 50 pieces. That means that when you find just another couple of pieces, it can have a major impact on your understanding of the overall picture."

Now, Jones and historian Margaret Condon—also at the University of Bristol—have found evidence to suggest that Weston was an early supporter of Cabot and that the merchant received a handsome reward from the king in 1500 for his exploration of the "new land."

In total, he was given 30 pounds—equivalent to about six years' pay for an ordinary laborer at the time—indicating that Henry was pleased with the outcome of his expedition, according to a paper published in the journal Historical Research.

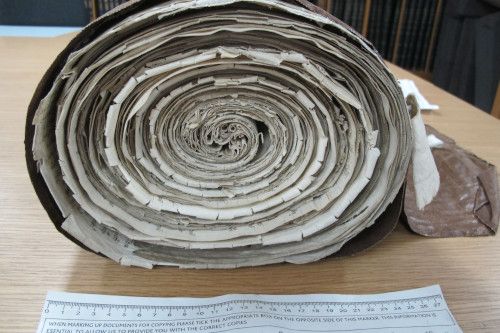

The evidence, in the form of a note, was uncovered after Condon painstakingly trawled through official tax records from the time, which take the form of huge parchment rolls made from the skin of over 200 sheep. Each "membrane" in the rolls is 2 meters long, and the note was so faint that it could be read only under ultraviolet light.

The authors also show that both Cabot and Weston received rewards from Henry in January 1498, indicating that the two explorers were working together long before the Bristol merchant left the city on his expedition in 1499. According to Jones and Condon, it is likely that Weston was one of the unnamed "great seamen" from Bristol that were prominent discussion topics for Italian diplomats and merchants in England during the winter of 1497-98.

Letters from the Italians suggest that Cabot took men from Bristol on his first expedition to North America in 1497 and that his supporters from the port were the "leading men" behind Cabot's subsequent voyage there in 1498. It is unclear what the exact outcome of the 1498 expedition was and how many of the ships returned.

"Finding this new evidence is wonderful!" Jones said in a statement. "Cabot's voyages have been famous since Elizabethan times and were used to justify England's later colonization of North America. But we've never known the identity of his English supporters. Until recently, we didn't even know that there was an expedition in 1499."

"We know that William Weston was probably one of the merchants who sailed with Cabot in 1497 and was certainly involved in the 1498 expedition, led by Cabot," he told Newsweek.

According to Jones, Weston's role in European exploration of the New World has been totally overlooked: "Until nine years ago nobody had ever heard of him," he said. "Yet he was the first Englishman to lead an expedition to North America. He was then forgotten, so finding him again is very exciting."

Weston spent most of his career working for others as an agent, rather than owning his own business. He was also an entrepreneurial gambler, who took risks and went places that others didn't. Sadly for Weston, he had some bad luck and a few disasters. However, he acquired knowledge and experience that made him a valuable companion and deputy to Cabot.

"In the end, Weston comes across as a bit of a chancer, who may partly have gone on his final expedition to avoid his house getting repossessed," Jones said. "But then that puts him in good company with a man like Cabot, who was also fleeing the law!"

Intriguingly, the study also confirms some of the research claims made by a deceased historian from the University of London, Alwyn Ruddock, who studied the early English voyages to the Americas for over 40 years. Ruddock never published her findings and, strangely, ordered that all her notes be destroyed when she died in 2005.

Among her more revolutionary hypotheses, which are yet to be verified, she suggested that a group of Italian friars who accompanied Cabot on his 1498 mission went on to establish the first European Christian colony and church in North America.

Ruddock also claimed that Cabot had explored most of the North American continent's east coast, from the Hudson Strait to Florida, by 1500. It's generally been supposed before that none of the coast of what is now the USA was explored by Europeans until the 1510s-20s, according to Jones.

"Given her extraordinary claims about what she'd discovered about the early English voyages to North America, I began investigating her assertions to see if they could be verified," Jones said. "Since then, I and others have been searching for the 'new documents' that provided the foundation for Ruddock's claims. We've now found over half of them and have published many of the key ones."

The early Bristol voyages didn't achieve their immediate aims of finding a route to China; this may explain Henry's willingness to order another voyage the following year led by Weston, one of Cabot's deputies. However, they did pave the way for exploration, trade and fishing by other Europeans, such as the French and Portuguese.

"Beyond that, the fact that Cabot had claimed America in the name of the King meant that from the later 16th century it was argued that England had 'title' to North America from its first land claims," Jones said. "That was then used to justify English/British colonization efforts from the 1580s onwards, which led to the development of the American colonies in the early 17th Century."

"And while it might seem silly today that an entire continent could be claimed by Cabot in 1497, it's worth remembering that those British claims still underpin the U.S. Government's land claims," he said. "Basically, the U.S. Government post-1776 assumed all British rights and claims as its own."

The expeditions in the 15th and 16th century form part of a long history of exploration and settlement in the Americas. Long before Europeans arrived, waves of people had come across from Siberia to Alaska, becoming what we now know as the Native Americans.

After that, we know that small groups of Vikings reached at least as far as Newfoundland circa 1000 A.D. and probably pressed further south at least as far as Nova Scotia. But they didn't stay long and had no lasting impact on the continent.

In the 15th century, the Portuguese, followed by the English and (lastly) Spanish, took up Atlantic exploration. Bristol mariners were certainly sailing west looking for new islands beyond Ireland by the 1470s, according to Jones.

"This said, while there are many claims that Bristol mariners, or perhaps mariners from the Basque Country or Portugal, reached America at some point during the later 15th century, there is really no hard evidence of discovery before Columbus in 1492," he said. "Most of these claims are routed more in local patriotisms, rather than evidence".

"In this context, it's worth remembering that Columbus's discoveries were limited to Cuba, Hispaniola and the north coast of South America: he never landed in any part of North America," he said. "Cabot's 1497 voyage from Bristol was important because it was the first of that era to reach North America and there are good reasons to suppose that during the many voyages from Bristol of the next ten years, the city's expeditions did explore most of the eastern seaboard."

This article has been updated to include additional comments from Evan Jones.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.