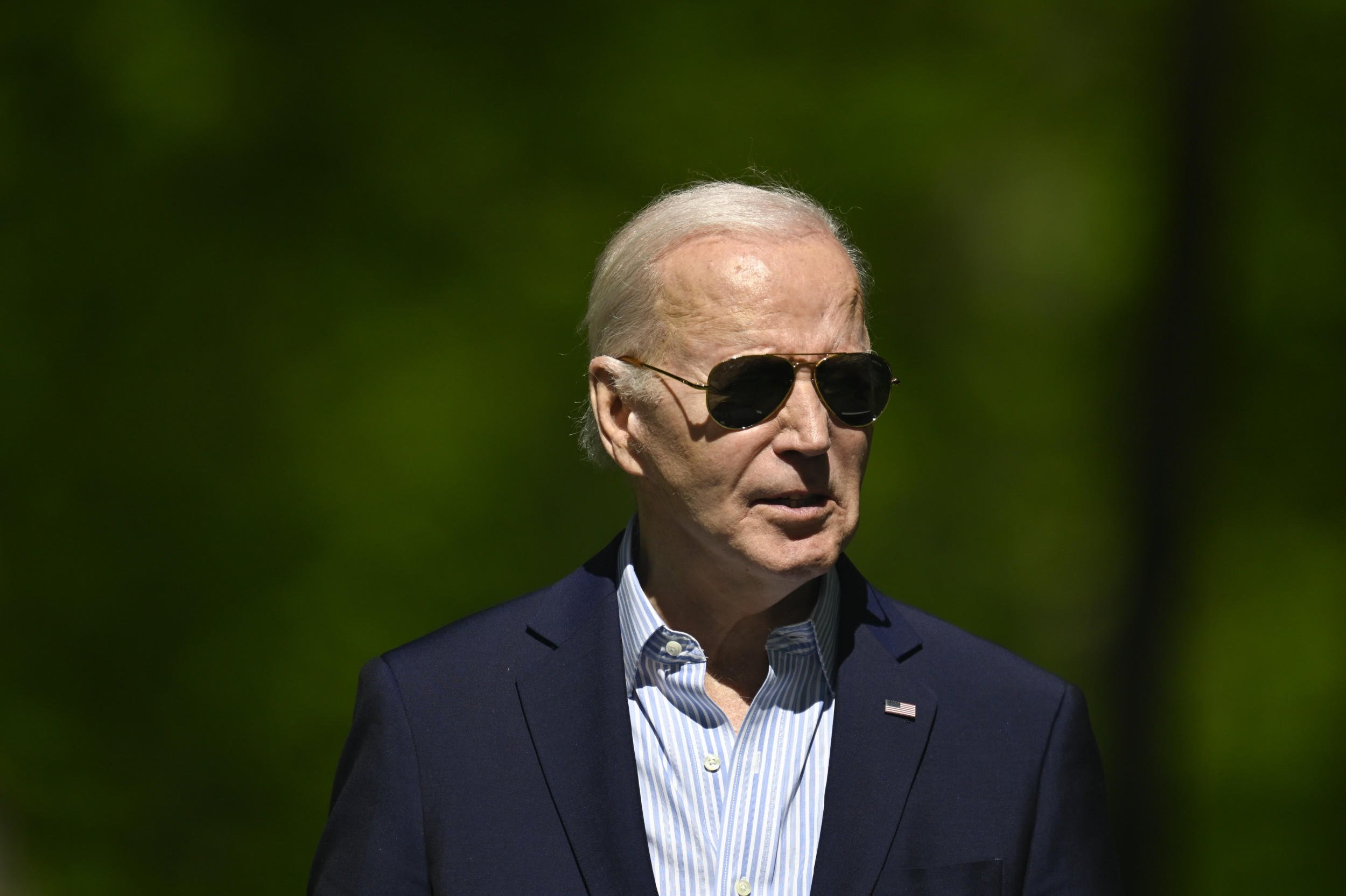

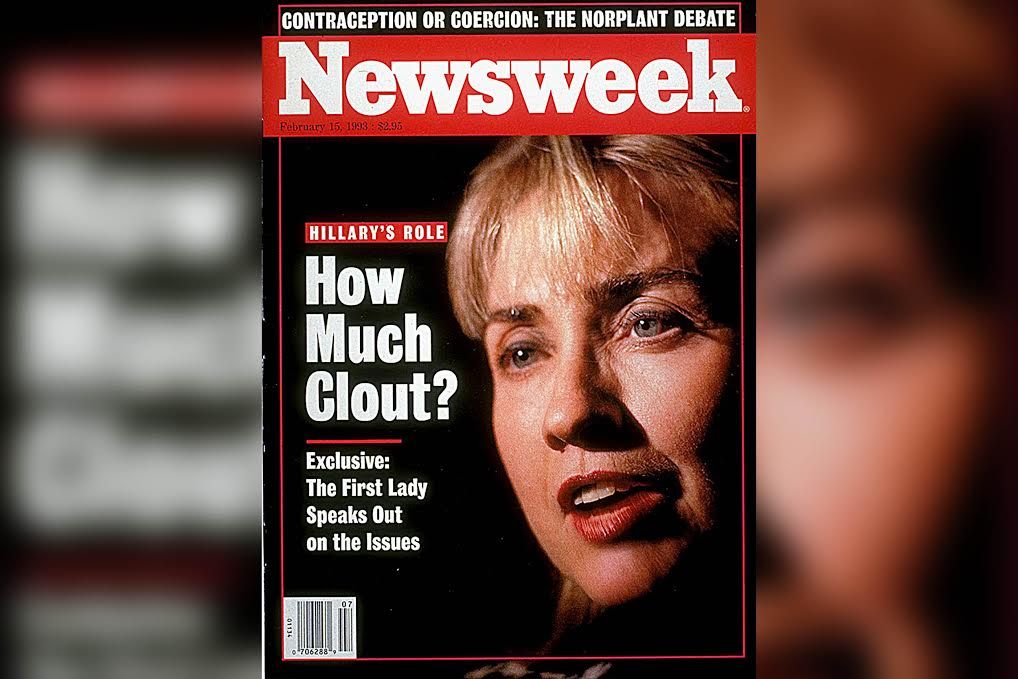

Hillary Clinton is gearing up to announce her presidential campaign, perhaps as soon as this weekend. So we're republishing our 1993 cover story on the soon-to-be candidate, published just a month after the Clintons entered the White House. Scroll down for Joe Klein's Q&A with the then first lady.

They sat in the Oval Office for 40 minutes: President Clinton and the woman he was considering naming as his second nominee for attorney general. Clinton and U.S. District Court Judge Kimba Wood of New York talked of many things, including, as the president put it, whether she had "a Zoe Baird problem" with her child-care arrangements. No, she said, and she had documents to prove it.

Fine, then, there was only one other person to see before the legal technicians and the FBI "vetted" her. So Wood headed upstairs to an office on the second floor in the White House's West Wing nerve center. There she spent 50 minutes talking to the person whose political network and personal views had helped her get in the door to begin with—Hillary Rodham Clinton. Mrs. Clinton, eager to see a woman chosen as attorney general, was impressed. No red flags were raised or seen. Soon word leaked out: Wood was very likely to get the job.

As the world now knows, Wood didn't. A week after her White House interviews, she withdrew from consideration last Friday when it became known that, in 1986, she had hired an illegal alien from Trinidad to care for her child. Unlike Baird, Wood was never actually nominated. Clinton aides insisted that their "vetting" process—and their political antennae—had worked this time around. But the embarrassingly persistent failure to find an attorney general (the New York Daily News headlined the story ALIEN II) renewed questions about whether the young Clinton administration was yet ready for The Show. "This makes the White House look horrible," said one Democratic senator. "Clinton has to have a smooth-running operation, and so far he clearly doesn't."

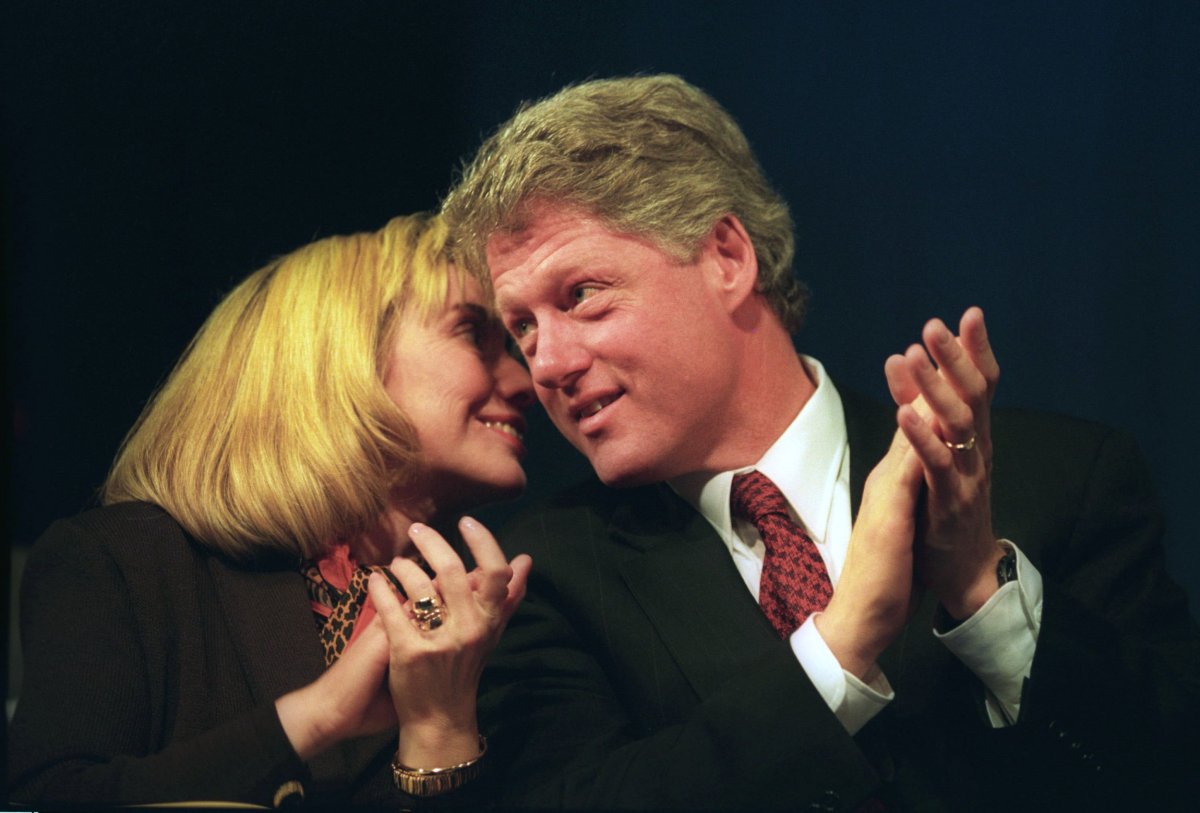

The other lesson of the week was more significant. The "operation" isn't being run by a "he" alone. As Wood's trip through the West Wing showed, the administration is something entirely new in American political life. It's a Team Presidency whose own act has no script—and whose political consequences are unknown. In an exclusive interview with Newsweek, her first as first lady plus, Mrs. Clinton spoke of her view of government's role—and, implicitly, her own. "We are all in this together," she declared, a comment that could apply as well to her and her husband.

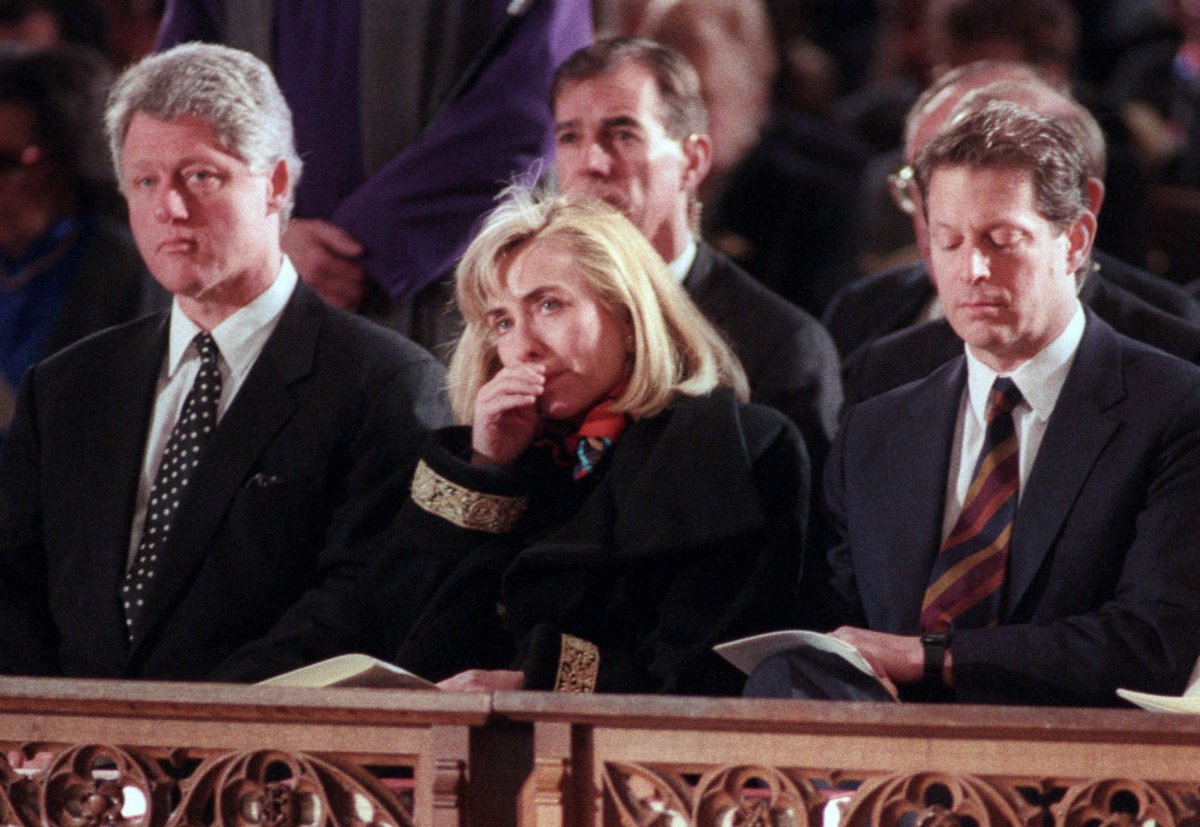

On many important decisions, including the attorney general choice, Mrs. Clinton is far more than a first lady. She has her own network, which stretches across the country and deep into the new administration. She has more senior-grade aides assigned to her than Vice President Al Gore. In politics, as in private life, the Clintons employ team survival strategies that serve both and give Hillary unprecedented clout. As one White House aide put it last week, she isn't just in the loop, she is the loop. The only question is when—if ever—Hillary's unique role will raise the issue of who's really in charge in the Oval Office.

It hasn't so far; she knows the limits and has other roles to play. All of them were on display last week—and she juggled them with the aplomb that has made her a popular role model not only for "career women" but for career men who choose to study her actions. As mom, she visited Chelsea's new school to watch her daughter's soccer team play (they won, 4-1). As ceremonial first lady she attended funerals and fussed over the menu for her first White House dinner. As new age first lady, she banned smoking in the White House complex and put more fruits and vegetables on the mess menu. "She is representative of what a majority of women are doing today," says Press Secretary Lisa Caputo. "And that is balancing career with family and entertaining."

But the "career" is getting the ink. As chair of the administration's task force on health care, she went to the Hill last week to pledge cooperation with the members. The visit produced some extraordinary scenes, among them an utterly comfortable woman sitting in a high-backed chair opposite the baron of congressional Republicans, Senate GOP leader Bob Dole. Aides to Dole (who is married to former Reagan and Bush Cabinet member Liddy Dole) said that their boss was impressed by her cool and savvy—and her promise to work closely with the GOP.

At a more substantive meeting with Democrats, she felt no need for icebreaking or bows to traditional roles. In charge of the administration's most important domestic initiative, reform of the nation's $800 billion health care system, she wasted no time on jokes or slaps on the back—let alone pecks on the cheek for friends. She acknowledged that sweeping reform would have powerful enemies; that Congress's input was crucial; that she knew enough to ask questions but not enough to draw conclusions. She was adjudged a hit. "She walked in there and took command," said Senator Bob Kerrey, who ran for the Democratic nomination against her husband. "I was very impressed."

'War room'

This week she takes her show on the road. Accompanied by Tipper Gore, Hillary will attend a conference on health care in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. The site is significant: Pennsylvania is the state in which Harris Wofford won a 1991 Senate race by stressing the need for a national health care system. Hillary's trip signals the start of what will amount to a new election campaign, this one to build support for health care reform. The administration will soon name a "campaign manager" for the drive; a "war room" in the White House complex will oversee it, with money from the Democratic National Committee. "She's running point," says Kerrey.

She has practice. The Clintons have decided to duplicate the tag-team strategy they used in Arkansas in the early 1980s to develop and sell a controversial package of educational reform. Hillary traveled to each of the state's 75 counties, holding hearings and selling change. She then helped lobby the legislature for successful passage of the final package. "They were a team, and Bill couldn't have done it without her," said Betsey Wright, Bill Clinton's former chief of staff as governor of Arkansas.

Much of Hillary's clout comes from the working relationship she and her husband have developed in politics. They perfected the team game in the 1992 campaign. Unlike most past first ladies, Mrs. Clinton didn't—and doesn't—operate by indirection. She is not a gatekeeper or silent adviser. In 1992, she made key decisions. It was Hillary, not Bill, who insisted that he quickly declare "victory" as the "Comeback Kid" in the New Hampshire primary, though he had finished second to Paul Tsongas. It was Hillary, not Bill, who moved to turn control of a floundering campaign over to consultant James Carville before the Democratic Convention. During the convention, she gave Carville the go-ahead to set up the famous war room that controlled day-to-day operations in the fall. When her husband was distracted or tired, it often was Hillary who forced him to focus on a speech he needed to write.

Like Bill, Hillary has her own network to tap; FOHs (Friend of Hillary) are almost as numerous as FOBs (Friend of Bill). Central to all of Hillary's political endeavors is Marian Wright Edelman, founder of the Children's Defense Fund. Despite her respect for Edelman, Hillary Rodham Clinton isn't quite the big-government liberal she is sometimes depicted as being by her enemies. Though she sided with Edelman on the need for a federally sponsored day-care system, she parts company with her on welfare policy, arguing for more emphasis on personal responsibility rather than direct federal aid.

But there's no doubt that Wood—and Baird—were propelled forward by Hillary's network. Edelman's husband, attorney Peter Edelman, has been a key outside consultant in the search for an attorney general. So has New York attorney Susan Thomases, who attended college with Wood and supported her nomination. The details of Wood's child-care situation were examined by White House counsel Bernard Nussbaum, another FOH. Mrs. Clinton, insiders say, has made it clear that she still favors the nomination of a woman in one of the "Big Four" Cabinet jobs; the other three (State, Defense and Treasury) are occupied by white males. Women's groups are relying on her to deliver. "She's someone we can talk to and count on," said Harriett Woods, chair of the National Women's Political Caucus.

High Ratings

So far, the team concept seems to be working—especially for Hillary. She's box office: She now outpulls Princess Di as a newsstand draw for People magazine. Most Americans, polls show, view her as a positive role model. Nervous Clinton aides profess to be pleased with her prominence. The White House's internal polls show her with a higher approval rating than her husband's; aides say that there's also widespread approval—more than public polls show—for her taking on the specific assignment her husband has given her, health care reform. Her image is a needed antidote, one aide sourly observed, to the image of amateurism and drift in the administration. "Right now, she's the best thing we've got going for us," he said.

But there are risks, for Hillary—and for her husband. For one, there's the chance that health care reform will flounder. "If the issue gets too controversial, she may be out there all alone," says Kerrey. She risks being accused of using her marriage as a route to advancement. And if Bill Clinton doesn't like the results, what does he say to Hillary—in public? "If it's just some politician heading a task force, you get rid of him and repudiate his report," says Democratic poll-taker Geoffrey Garin. "But if you don't like your wife's work, it's kind of hard to distance yourself from it."

Republican strategists are glad to discuss what they see as a bigger risk: that Hillary's prominence will somehow undermine her husband's political authority. The risk to Clinton has nothing to do with gender or marital status, says GOP poll-taker Bill McInturff. It's purely a question of ensuring that the American people see no unaccountable power hovering outside the Oval Office. "People take the power of the presidency seriously," says McInturff, "and Clinton has to show that he's in charge."

He did so late last week once he turned his attention, again, to Kimba Wood. She had done nothing illegal. In early 1986, when she hired her nanny, employing an undocumented alien was not against the law. Judge Wood—unlike Baird—complied with tax and registration requirements. A source close to Wood insisted that she had fully apprised officials of the details, and suggested the administration became skittish about how her situation would play politically. But White House sources insisted that she never directly stated one fundamental fact: that she had hired an illegal alien.

Clinton got the picture, in the nick of time. Even as word was leaking last Thursday evening that Wood was the choice, Nussbaum and White House personnel director Bruce Lindsey were meeting with Clinton. Nussbaum finally had gotten to see documents Wood had provided that day. While she seemed to be on firm legal ground, her story was too reminiscent of Baird's to be defended in the age of Talk Show Democracy. The dreaded name of Rush Limbaugh was invoked. Bill Clinton made the call: Wood would not be nominated. And Hillary wasn't in the room.

'We Are All in This Together': Hillary Speaks Out on the Issues

Hillary Rodham Clinton played by a strict set of rules during the presidential campaign. She not only maintained "message discipline" but also radio silence on the domestic-policy issues that she'd been working on for 20 years. Last week Mrs. Clinton agreed, for the first time as first lady, to reopen the discussion of policy with Newsweek's Joe Klein.

The conversation took place in the family residence of the White House, in a sitting room Mrs. Clinton said "will be the family room, if I ever get a chance to unpack." The first lady, outspoken about children and poverty when she was in pre-campaign mode, was more cautious now—and near mute when the conversation strayed from policy to the events of the week—but she did reveal herself to be more of a moderate than previously assumed. She agreed with conservatives that merely providing jobs for poor people isn't enough, that "behavior modification"—including "sanctions" for misbehavior—is appropriate for those trapped in a "culture of poverty." Mrs. Clinton made it clear that she hoped the new era of government altruism, which she will help create as the president's most influential domestic-policy adviser, will be as tough-minded as it will be compassionate. Excerpts:

Klein: Senator Moynihan and others believe the nature of poverty changed in the 1960s, that a pattern of chronic dependency developed among the poorest of the poor. Do you agree?

Clinton: I agree that the culture of poverty in this country has become institutionalized to an extent that is surprising to me and many others. Poverty has been with us since the beginning of time, and in many cultures there is a permanent underclass with all the problems that that suggests. It is contrary to the American ethos and history of progress that we would see that developing and becoming institutionalized in our country. There is nothing new about having poor people in our midst. What is very new is that we now have the institutionalization of that culture of poverty in ways that are difficult to reconcile with the whole concept of upward mobility, change, the American dream. And so those observers, including Senator Moynihan, who point that out as one of our major problems are absolutely right.

How do we as a society address the 15-year-old mother on welfare? What do we owe her? Can we demand a set of behavioral standards from her?

Sure, I've been talking about that since 1973. You know, I am one of the first people who wrote about how rights and responsibilities had to go hand in hand. Nobody in the political campaign seemed to understand that that was what I was saying, except for the people who actually read what I wrote.

The new assistant secretary of housing, Andrew Cuomo, developed a program for homeless women and children with a very strict set of rules. If the rules are broken, you are kicked out. Is that sort of standard too harsh?

No, no. I have advocated highly structured inner-city schools. I have advocated uniforms for kids in inner-city schools. I have advocated that we have to help structure people's environment who come from unstructured, disorganized, dysfunctional family settings. Because if you do not have any structure on the outside, it is very difficult to internalize it on the inside.

When you talk about moving someone to work from welfare in two years, what happens to people who don't want to work? Would you impose sanctions?

Oh, I think you have to. What happened in Arkansas is that people who refused for whatever reason to participate had their benefits cut.

Your husband made the argument during the campaign that cutting benefits only hurts the children.

Well, the benefits that were cut were the adult benefits. There's a real problem with maintaining even a minimal standard of living. It's a signal. It's a behavioral signal—very few people, if they believe they're going to suffer consequences, will persist in that behavior. What we have to figure out how to do is to have a system that offers enough encouragement and assistance in real terms, not the kind of charades that we've seen over the last 12 years. [But there should also be] sanctions so that the message is loud and clear [that] certain behavior is no longer going to be tolerated. But let's be sure that we get the best possible help and support and encouragement and incentives to those that we think we can actually help....

Part of what I've done for 20 years is to figure out how we do that. And I have not fallen easily into any camp, like this is the dogma that we have to adopt, because I don't think there is any camp out there. I think we are piecing together a different set of approaches to try to deal with what has been the breakdown of internal control, of internal responsibility. But if all we do is think in terms of people that are already impoverished, we miss some of the bigger social trends. I think the same message of responsibility should not go just to the 15-year-old welfare mother but should also go to the college student who cheats, should also go to the businessperson who is irresponsible with respect to polluting our environment.

What are your feelings about affirmative action? Has it helped? Do you think at a certain point it becomes redundant?

Oh, I hope it does, yes, I think that we can get to the point where we truly are color-blind. [But] we're a long, long way from that right now. I think the existing framework that we have now is appropriate. I don't think we should go any further, and I think we should move toward a time when we can eliminate it.

When some women's groups say that one out of the four top Cabinet positions should be a woman, is that a quota or a call for diversity?

I don't know, I can't speak for them, so I don't know what they mean by that. But I think that it is important if you are in a position of leadership to open your mind. There are a lot of good ideas that have come up from people's individual experiences, that have been affected by their gender or their ethnic or racial background. I think we will be stronger for having the kind of thinking that breaks through stereotypes and looks for well-qualified, meritorious people who have in the past not been, perhaps, viewed as someone who could meet a certain job requirement.

Do you think that you've had the problems you've been having in selecting the attorney general because of a quota system?

No.

Do you think that the problems that your most recent nominees for attorney general have had says anything about the day-care situation in this country?

Probably, but I haven't analyzed that.

I know that you're just getting started on health, but is there a program you can point to and say that's the direction we want to go?

Well, it's too early, and I'm not sure that there is any model, but there are pieces of system that have to be addressed. One is that individuals are going to have to also be responsible to take care of themselves and to have an understanding of what causes health as opposed to illness, and I think that's a piece of the whole responsibility ethos that the president has talked about.

In the 1930s the poorest segment of the population were the elderly, and now they're the most wealthy. Do you think the elderly are holding a disproportionate percentage of the nation's wealth?

No. I think what has happened, though, is that we had a system to care for the elderly—it's Social Security and Medicare. It has provided a safety net. What we haven't done is figured out how to provide that same kind of system for children. The more poor children we have, particularly those in the most disorganized settings, the less likely it is we'll be able to continue to provide security in the most basic sense for the elderly or anyone else.

Because of crime?

Because of crime, because of declining productivity, because of a declining tax base—you can list all of it. Personal security is at the root of everything that I think we have to be focused on. Personal security on the streets and in your homes, personal security to not worry about being sick and facing catastrophe, personal security in some job that we can hold out to people.

You can go down the line and nearly every issue we look at, whether it's instilling responsibility and self-esteem in children who are living in our inner cities or personal security to our elderly citizens who lock themselves behind their doors because of those same children. We are all in this together.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.