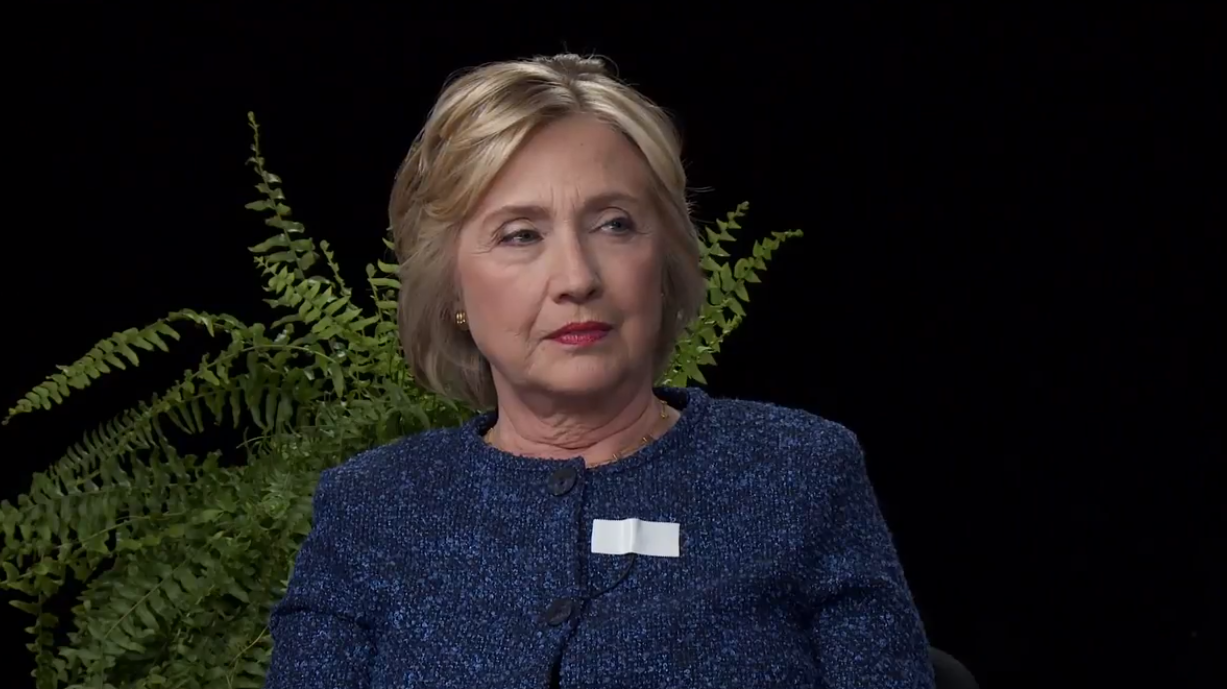

Why is Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton underperforming among young voters?

Since several polls released over the past ten days indicated that the inclusion of third party candidates revealed a precipitous decline in Millennial support for the Democratic nominee, we have gotten no shortage of theories from the punditry purporting to answer this question. Mother Jones's Kevin Drum blames Bernie Sanders. New York Magazine's Jonathan Chait agrees. The Daily Beast's James Kirchick says "cynicism" and an inexplicable aversion to permanent imperial war are the problem. New Republic's Brian Beutler, contra Kirchick, offers a take so hot that it has single-handedly revised global climate change projections: Young voters are insufficiently familiar with the horrors of the Bush administration. The given causes vary but the consensus is clear: Young voters are pathological and the cure is to disabuse them of their ignorance.

Here is my own wild take on why millennials don't support Clinton "enough": Many younger American voters, perhaps a sufficient number of them to seriously imperil Clinton's chances, have significant ideological differences with the candidate. That's my theory. Many liberal pundits seem unimpressed by this idea perhaps because it suggests that votes must be earned in a democracy, but it does have the benefit of the evidence.

Hillary Clinton does not support single-payer health care; Young voters do. Hillary Clinton is among the more hawkish members of the Democratic Party; Young voters are not. Hillary Clinton is a capitalist, and even within a capitalist party, she is in both perception and in practice unusually comfortable with capitalism's worst practices. Millennials, by contrast, reject the entire economic system by a bare majority. They are no great fans of financial institutions or free trade. This should not be surprising in a year when very few voters of any age group are particularly enthusiastic about their prospects.

The liberal punditry might be forgiven for underestimating the depth and seriousness of these differences had these young people not voted overwhelmingly and across all other demographic lines for a different candidate. The Clinton campaign might be forgiven for imagining these voters would "come home" had it not spent the weeks since the Democratic Convention fundraising and playing Bush administration endorsement bingo. The trouble is not that young people are insufficiently familiar with the neoconservative horror show of their own childhoods. The trouble is that the candidate they are meant to support does not appear to find that show particularly horrifying.

Indeed it is difficult not to imagine that the punditry has refused to endorse the maddeningly simple conclusion that young voters are reluctant to support a candidate who does not represent their policy preferences because such a conclusion might undermine the need for so much well-compensated armchair psychology on their part.

All of this consternation is made stranger still by the fact that despite all of this, millennials remain Clinton's strongest age group in the election. Kevin Drum insists that this is not the point (rather, he argues, "The issue is relative support compared to previous years... [that] millennial voters prefer Hillary Clinton at far lower levels than they preferred Barack Obama four years ago," which is to say that a different group of millennials preferred a different Democratic candidate against a different set of opponents in a different election), but surely if we are going to begin assigning blame for a theoretical Trump Presidency we ought to assign it to the generations actually breaking for Donald Trump. This would be like asking whether or not George W. Bush's 2000 victory over Al Gore had something to do with the hundreds of the thousands of registered Democrats who voted for the Republican candidate: it might suggest something has gone wrong not in the fickle minds of young people, but in the Democratic Party.

Young people are not being asked to support Hillary Clinton in a vacuum, however.

They are being asked to support her against Donald Trump, a candidate vastly more alien to their preferences. They are being asked to bite the bullet and pull the lever for the same system that has walked to the precipice of the presidency a man too clownishly inept to even qualify as a proper fascist because that system, in the short term, is their best chance to deny that clown the White House. This case, when stripped of its usual attendant condescension ("self-indulgence", "purity", "foolishness", "I was young and didn't vote for Gore/Carter/Humphrey once"), at least has the benefit of appealing to young leftist's immediate interests: We accept that Hillary Clinton is not your ideal choice, but we're playing defense right now. It is not that the present rash of Millennial diagnostics have not included appeals to the Trump Threat—they always do. What is notable here is that pundits lack the confidence to believe that this threat, on its own, is sufficient. Why is it so important that Clinton not only be nominally preferable to Trump, but that objections to Clinton—even in a vacuum—must be explained away?

I would like to suggest that the threat these young voters pose to technocratic liberalism is not the possibility of electing Donald Trump. Despite Clinton's flagging numbers, her chances of success remain high. Rather, the fear is that if younger voters really are committed to a host of ideological positions at odds with the mainstream of the Democratic Party, then that Party, without a Trump-sized cudgel, is doomed. It should not escape anybody's notice that politics by negative definition—the argument, at bottom, that "we're better than those guys"—has become the dominant electoral strategy of the Democratic Party, and that despite the escalation of the "those guys" negatives, the mere promise to be preferable has yielded diminishing returns. At some point, the Democratic Party will either need to embrace a platform significantly to the left of their current orthodoxy, or they will lose.

There are only so many times one can insist that young voters capitulate to a political party's sole demand—vote for us!—in exchange for nothing.

This might not seem such a bad thing. Positions shift. Parties evolve. A serious threat of millennial desertion might lead to a natural compromise: support, in exchange for real policy concessions going forward. So why have liberal pundits resisted such a move? Why are they intent on not just defeating but discrediting the ideological preferences of the young left, dismissing them not as a legitimate divergence but as mere ignorance and confusion?

Perhaps the theory that political choices meaningfully reflect political preferences can help us here, as well. Many older people, including liberals, tend to be more conservative than younger voters. These ideological preferences are real, and we should take them as seriously as they should take the preferences of millennials. These older liberals would like their vision of society to prevail. They would like to win. It is therefore in their interests to discredit and defeat opponents of that vision, be they reactionary nativists or young anti-capitalists. One way to defeat them is to use their positions as public commentators in order to attack those opponents, to call them confused and unserious and dangerous. And so they have.

A wild theory: There is no pathology here. Only politics. It's maddeningly simple.

Emmett Rensin is a writer based in Iowa City, Iowa. His previous work has appeared in Vox,The New Republic, The Atlantic and The Los Angeles Review of Books (where he is a contributing editor). Follow him on Twitter at @EmmettRensin.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.