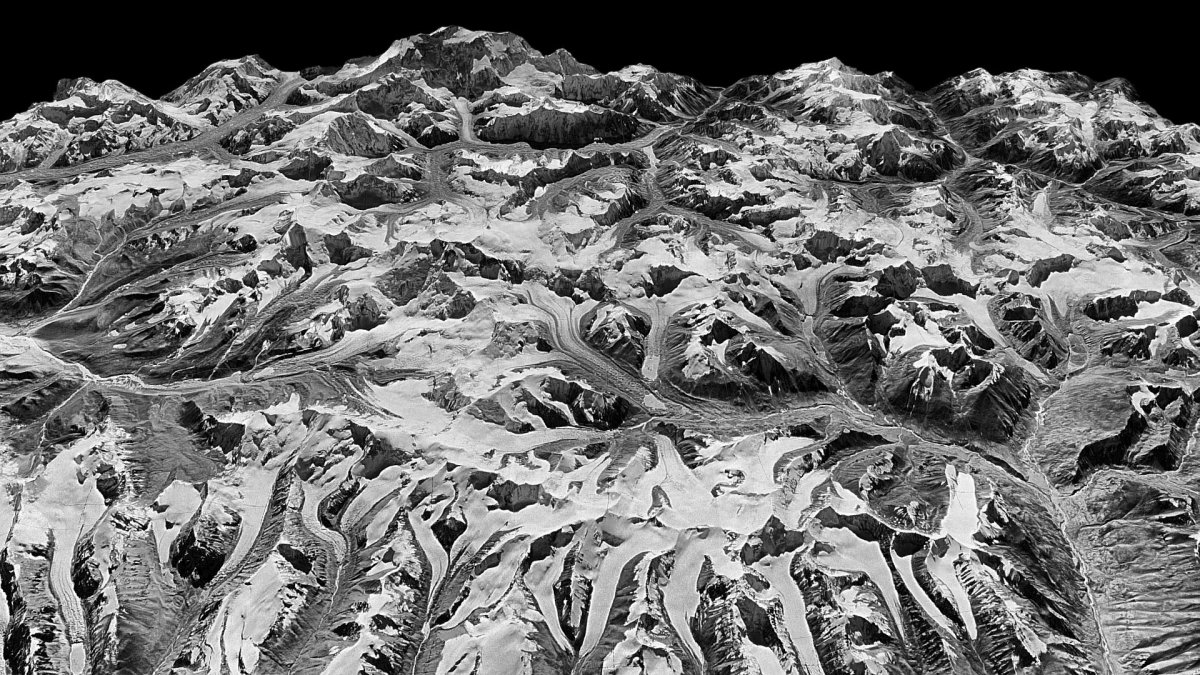

Declassified film from Cold War spy satellites has revealed that Himalayan glaciers are retreating twice as fast now than they were 20 years ago. By comparing the historical footage with modern NASA data, researchers were able to show that between 1975 and 2000, the glaciers lost about 10 inches of ice each year. From 2000, the rate of loss increased to 20 inches per year.

Joshua Maurer, from Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, and colleagues were looking to assess changes to glacier thickness across the Himalayas. In total, they analyzed 650 glaciers in India, China, Nepal and Bhutan, representing about 55 percent of the total ice volume in the Himalayas.

"The Himalayas have been a hotspot for glacier research in recent years, as we realize how vulnerable the region is to climate change," Maurer told Newsweek. "Because it is so difficult to access these remote glaciers via field studies, satellite imagery has emerged as the primary tool for observing the region."

The footage, from U.S. spy satellites and declassified in the mid-2000s, allowed scientists to digitally reconstruct the glacier surfaces. "This was possible because multiple satellite images were taken from different angles," Maurer explained. "Then, by taking the difference in elevation between the reconstructed historical glacier surfaces and the modern glacier surfaces, we calculated a change in ice volume for hundreds of individual glaciers."

NASA research shows that since 1880, global temperatures have increased by 0.8 C. Two-thirds of this warming has taken place since 1975.

Publishing their findings in the journal Science Advances, the team found Himalayan glaciers are retreating twice as fast now as they were at the end of the 20th century. Data from meteorological stations in Asia's high mountains suggests the temperature in the Himalaya region increased by 1 C between 2000 and 2016—a factor the scientists say may be driving the observed glacial retreat.

"The fact that we see a similar amount of glacier melting across such a large and climatically complex region is really not surprising if we consider the degree of atmospheric warming which has occurred," Maurer said.

However, he said the findings are important as the Himalayan glaciers contribute meltwater to the rivers that millions of people rely on. Changes to this water source could have a severe impact on the population.

The retreating ice is also causing many glacial lakes to grow. These lakes are often unstable and have the potential to cause "outburst floods" that can devastate the communities downstream from them.

To predict how Himalayan glaciers will melt as temperatures continue to rise, scientists must understand how they have reacted to climate change over recent decades, Maurer said. Research from February suggested that up to two-thirds of ice cover at Himalayan glaciers could be gone by 2100, if global warming continues on its current trajectory.

"If the glaciers disappear, river flows will be reduced—by how much depends on the region. More arid regions in the Indus watershed will likely be hit the hardest," Maurer said. "This is a complex topic, and still an area of ongoing research.

The team now hopes to examine other mountainous regions using the same methods employed in the current study. This, he said, could help improve the accuracy of models of changes to glaciers and water resources in the future.

Joseph Shea, a glacial geographer at Canada's University of Northern British Columbia who was not involved in the study, said the findings show even glaciers in the world's highest mountains are being impacted by increases in global air temperature. "In the long term, this will lead to changes in the timing and magnitude of streamflow in a heavily populated region," he said in a statement.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Hannah Osborne is Nesweek's Science Editor, based in London, UK. Hannah joined Newsweek in 2017 from IBTimes UK. She is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.