Anti-vaxxers are in the news regularly—the World Health Organization even named vaccine hesitancy one of the ten biggest threats to global health in 2019.

But the anti-vax movement is nothing new—in fact, it's as old as vaccines themselves.

1796: The smallpox vaccine is introduced

In the late 1790s, smallpox outbreaks devastated Europe, killing approximately 400,000 people a year and leaving many more blind or disfigured. Chinese medicine had recognized centuries earlier that survivors of smallpox subsequently became immune to the disease—in fact, as far back as the 9th century, healers inoculated patients by scratching smallpox scabs and blowing the powdered material up healthy patients noses.

Variolation, rubbing powdered smallpox scabs onto small scratches in the skin, was introduced in the West in the 18th century. It still involved exposing a healthy person to smallpox (and possibly other illnesses, like syphilis) but it had a much lower mortality rate than contracting smallpox naturally. That didn't stop vaccine denialists: When Cotton Mather promoted variolation in the Massachusetts colony, they threw bricks through his window and called him a child-killer.

It was Scottish doctor Edward Jenner who popularized the idea of infecting patients with the similar, but much milder cowpox virus to immunize them against smallpox. Jenner published his findings in 1796 and, by 1800, more than 100,000 people had been vaccinated against smallpox in Europe. That same year, Harvard medical professor Benjamin Waterhouse performed the first vaccinations in the United States—on his children and servants.

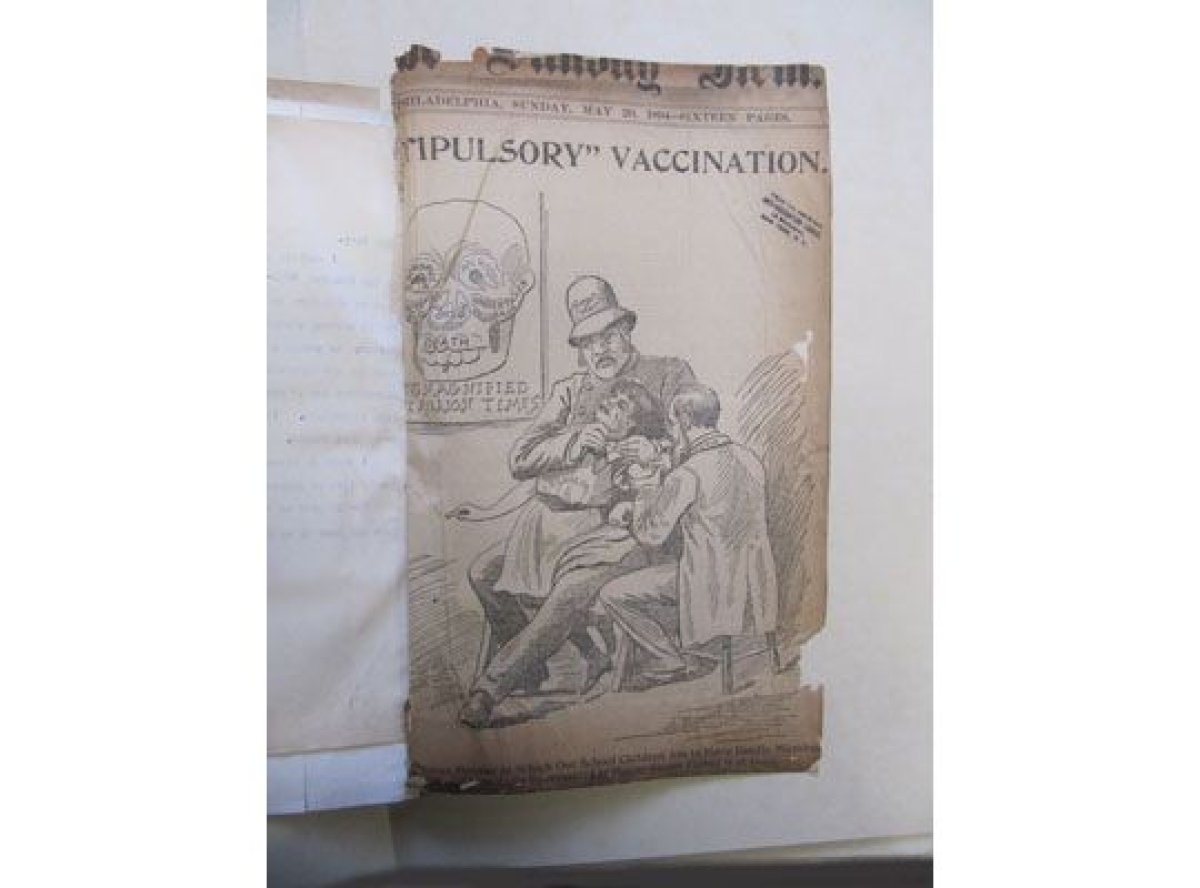

Thus the modern-day vaccination was born—and so, too, was the anti-vax movement: One of the earliest bits of anti-vaxxer propaganda also appeared around 1800—a French cartoon of two men weilding a giant syringe and pulling a monster behind them, as a group of children run in terror. In 1802, the English engraving The Cow-Pock-or-the Wonderful Effects of the New Inoculation showed newly vaccinated people sprouting cow heads from fresh injection sites, a reference to the pus taken from cowpox-ridden bovines that was used in smallpox vaccines at the time.

Another English doctor, Benjamin Moseley, emerged as a prominent early anti-vaxxer: Moseley still endorsed variolation and this new treatment threatened his livelihood. In an 1806 essay, he claimed mixing cow matter into humans was a violation of natural law. He described fictional post-vaccination ailments like "cowpox face" and speculated that British women "might wander in the fields to receive the embraces of the bull."

Other early anti-vaxxers argued that vaccinations perverted God's will: In the 1850s, John Gibbs preached that there were a fixed number of diseases and if smallpox was eliminated, other illnesses like measles would occur more frequently. Gibbs also taught that, though often fatal, smallpox should be encouraged because it '"relieves the system of humours that ought to be carried out of it, and is a healthy process."

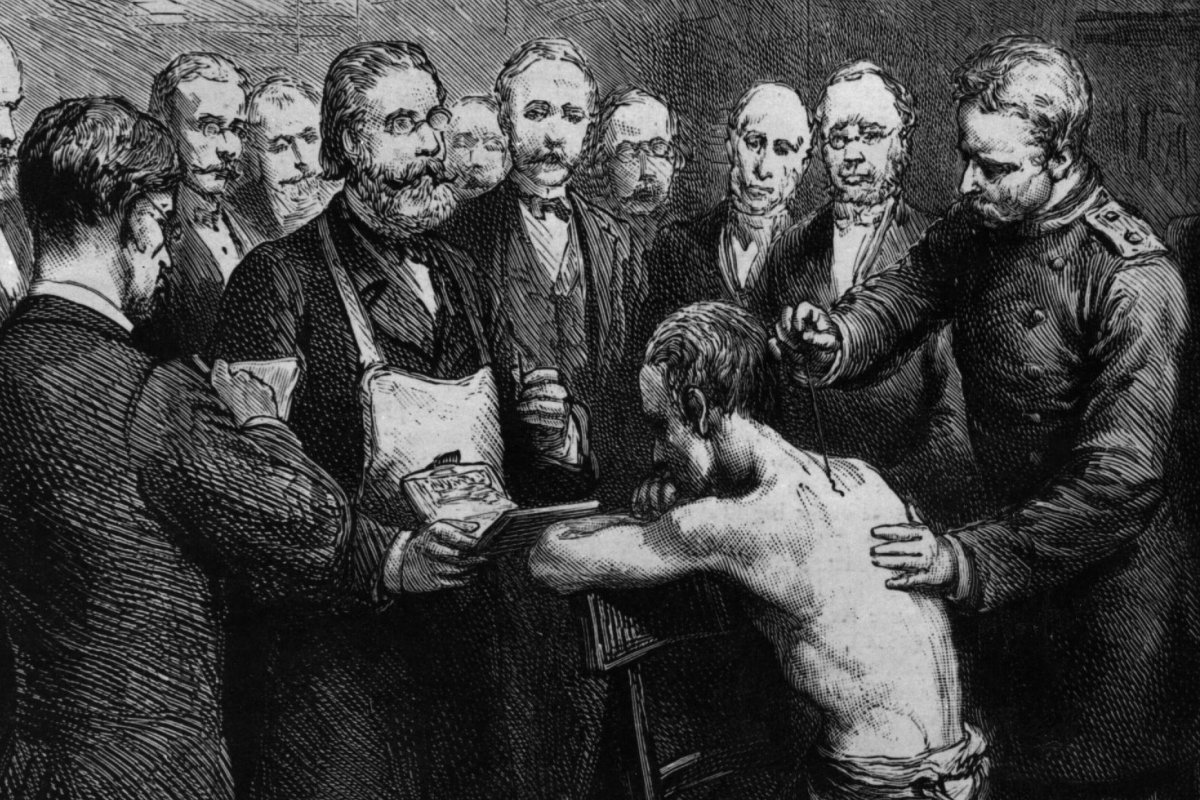

1853: The smallpox vaccine becomes compulsory in England

The Vaccination Act of 1853 made smallpox vaccinations mandatory for all infants under three months, levying fines and prison terms against parents who refused. It spurred anti-vax sentiment throughout the country: Violent riots broke out in Ipswich, Henley and Mitford. In London, the Anti-Vaccination League was formed.

After a 1867 law expanded mandatory vaccination to all children under 14, there was even more dissent—John Gibbs, long with his brothers Richard and George, founded the Anti-Compulsory Vaccination League that same year. A journal, the Vaccination Inquirer, was started in 1879 by the London Society for the Abolition of Compulsory Vaccination.

This time, the anti-vaxxers got their way: An 1898 act in Parliament removed cumulative penalties and introduced a "conscious clause" that allowed parents to opt out of vaccinating their children.

1870s: The American anti-vax movement gains momentum

British reformer William Tebb began spreading anti-vax propaganda to Americans in the 1870s, including the (fictitious) statistics that 25,000 British children were "slaughtered" each year because of vaccines and that 80 percent of smallpox deaths were among people who had been vaccinated. Tebb's arguments encouraged anti-vaxxers in the U.S.: The Anti-Vaccination League of America held its first meeting in New York in 1882.

The American anti-vaxx movement was also galvanized by the proliferation of patent medicines and homeopathic "cures" in the mid-to-late 19th century. Laws were extremely lax: Anyone could call themselves a physician and make claim that lifestyle, diet and medicinal herbs were enough to ward off even the most serious diseases. Evidence-based, state-sponsored vaccinations programs directly threatened these snake-oil salesmen—and they fought hard against them.

Other anti-vaxxers had a more libertarian bent, viewing compulsory vaccinations as an intrusion on personal liberty. The 19th century was also an era of tremendouz urbanization in America and vaccinations became a flashpoint for fears about the dissolution of a more autonomous agrarian society.

1885: Up to 100,000 anti-vax demonstrators march in England

Throughout the 19th century, working class British parents continued to complain that mandatory vaccinations violated their right to make choices for their own family: In 1869, the Leicester Anti-vaccination League was formed. It proved so successful in sowing skepticism that the number of unvaccinated children in the city grew from seven in 1874 to almost 2,000 a decade later. In 1881, the MP for Leicester, P. A. Taylor, wrote an open letter titled Current fallacies about vaccination, and 200,000 copies were circulated.

Anti-vax books and journals advised parents on how to get around compulsory vaccinations. In 1885, nearly 100,000 demonstrators flooded Leicester to protest compulsory vaccination laws. They carried children's coffins and beheaded an effigy of Edward Jenner.

Anti-vax sentiment spread to former colonies, too: In 1885, a mob of more than a thousand people in Montreal gathered outside a provincial health board office—smashing windows, breaking doors and reportedly even firing guns—to protest mandatory vaccinations in Canada.

1905: Mandatory vaccinations ruled legal in the U.S.

By the early 20th century, around half of all states had vaccine requirements. But lack of enforcement meant that many unvaccinated children slipped under the radar. Minnesota legislators bowed to anti-vax pressure and passed a law banning compulsory vaccination for schoolchildren in 1903. That measure would be blamed for a smallpox epidemic in 1924 that saw 28,000 people infected. (Anti-vaxxers also succeeded in repealing compulsory vaccination laws in California, Illinois, Indiana, West Virginia and Wisconsin.)

After Swedish immigrant Henning Jacobson was arrested for defying Massachusetts' mandatory vaccination laws, his case went before the Supreme Court. In a landmark 1905 ruling, the justices ruled against Jacobson—a Lutheran pastor—by holding up proof that vaccinations provided herd immunization and that states had the right to impose mandatory vaccinations for the greater good of the community. The ruling was balanced by outlawing forcible vaccinations, though, and resistance continued: In 1928, a group of visiting health officers were driven out of Georgetown, Delaware, by an armed mob of anti-vaxxers.

One of the most prominent leaders of the early 20th century anti-vaxxer movement was Lora Little, a mother who blamed the death of her only son on the smallpox vaccine. Hospital records indicate Kenneth Little died of diptheria more than six months after receiving his vaccination, but Little insisted "the artificial pollution of [his] blood," had fatally weakened her son's system.

Little claimed the American medical establishment was a tool of the U.S. government and that compulsory vaccinations set a dangerous precedent for the state to control people's bodies. In 1898, she founded The Liberator, a monthly magazine that praised healthy diets an active lifestyles and condemned vaccines. Her 1906 book, Crimes of the Cowpox Ring: Some Moving Pictures Thrown on the Dead Wall of Official Silence , painted vaccine manufacturers as powerful and greedy and cataloged the stories of hundreds of American children she believed to be vaccine-injured. In 1916, while speaking with servicemen in North Dakota, Little told them to resist the vaccinations they were required to receive and was arrested for inciting mutiny under the Espionage Act.

1970s: U.K. whooping cough epidemic

Efforts during WWII led to the creation new vaccines, but anti-vax sentiment still flared up throughout the 20th century: In the 1970s, the diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis (DTP) vaccine was blamed for neurological conditions in some British children, even though numerous studies indicated "no close association with their brain disease was possible."

DTP vaccine adherence in the U.K. fell from 81 percent in 1974 to 31 percent in 1980, resulting in major pertussis (whooping cough) epidemics in 1977-79 and 1981-83. In 2012 the UK experienced another major pertussis outbreak, with more than 9,300 cases in England alone—more than ten times the average in recent years.

1998: Lancet study links vaccines to autism

In 1998, British gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield published a report liking the combination measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine—routine since the early 1970s—to autism and bowel disease in infants. But subsequent researchers were unable to reproduce Wakefield's results and, in 2004, and investigation by the Sunday Times revealed he had fabricated his research.

The Lancet withdrew his report and Wakefield was barred from practicing medicine in the U.K., but he moved to America and doubled down on his anti-vax claims: He directed the anti-vaxxer propaganda film Vaxxed: From Cover-Up to Catastrophe in 2016, the same year he attended Donald Trump's inauguration ball.

As recently as March 2019, a study of 600,000 Danish children determined there was no connection between the MMR jab and autism. But Wakefield's research continues to fuel skepticism: A 2018 survey by Zogby Analytics revealed that nearly 20 percent of Americans believe vaccines are unsafe.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.