For Hollywood, China is a big opportunity and maybe a bigger headache. The opportunity is that it is an enormous movie market, expected to soon become the biggest in the world. As Tuna Amobi, an entertainment analyst with investment research firm CFRA, says. "Every studio understands that to be successful internationally, the growth lies in China."

The headache is that if Western producers want to show—or make—a film in China they must first deal with an army of bureaucrats who decide what Chinese audiences can see. Their names are appropriately Orwellian: the State Ethnic Affairs Commission; the State Administration for Religious Affairs; the Publicity Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China; the Ministry of State Security and Safety and many more. Their jobs are to make sure not only that China is always portrayed favorably, but also that some subjects are never mentioned, Chief among them are the three T's: Taiwan, Tibet, Tiananmen. Also off limits: president Xi Jinping's attempt to extend his term of office indefinitely; the detention and torture of 13 million Uyghurs, Kazakhs and Turkish Muslims; the suppression of Christianity in China and the harassment of pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong.

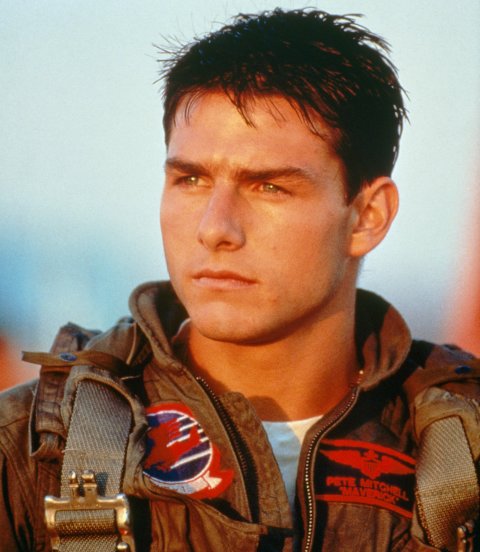

Hollywood has mostly gone discreetly along with that since China began opening to the western movie business in a big way in the 1990s (for a look at some of the films that have been censored, see page 41). Last summer Paramount Pictures, for instance, released a trailer for Top Gun: Maverick, its upcoming sequel to the 1986 blockbuster, co-produced with Chinese internet giant TenCent. (Originally set for release this June, the pandemic has pushed the film back to December.) One shot features Tom Cruise, as the now middle-aged title character, putting on what looks like the brown leather jacket he wore in the first film. In 1986, the jacket had commemorative Navy exercise patches featuring the flags of Taiwan (which split from mainland China in 1949) and Japan (China's bitterest regional rival). In the new trailer, the jacket looks the same, but the flags are gone. Paramount declined to talk about it with the press.

There are some small but real signs, however, that the days of studios quietly tailoring American movies for China are numbered. U.S. relations with China have grown tense across the board. The change began with President Trump's trade war and now charges and counter-charges about COVID-19, Beijing's crackdown on Hong Kong and its ambitions in the South China Sea have only increased the temperature.

Meanwhile, although public discussion of Chinese censorship remains taboo for the big studios, some filmmakers have been increasingly willing to complain and even, in a few cases, resist. This spring, Congressional conservatives proposed legislation that would punish American producers for censoring their films to satisfy Beijing. Exhibit A? Tom Cruise's jacket. As Texas Republican Ted Cruz asked from the floor of the U.S. Senate this May, "What message does it send that Maverick, an American icon, is apparently afraid of the Chinese communists?"

Paramount, Universal Pictures, Disney, 20th Century Fox, Sony Pictures, MGM and Warner Bros. declined to speak to Newsweek about their China strategies. Newsweek, however, spoke to dozens of current and former movie industry insiders, all of whom said censorship is the primary impediment into breaking into the Chinese market in any meaningful way.

Staggering Potential

Before coronavirus shuttered theaters worldwide, China was on track to become the planet's biggest movie market in 2021, with $11.2 billion in box office receipts compared to $10.9 billion for the U.S, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers. At the end of 2019, China boasted 69,000 movie screens, up from just 9,700 a year earlier, according to The People's Daily, a mouthpiece for the country's ruling Communist party. CFRA analyst Amobi, says, "2020 is a lost year, but there's no question China will regain its prominence probably in 2021."

Hollywood has been chasing Chinese revenues since 1971 when President Richard Nixon ended a two-decade trade embargo and allowed studios to license their films to China, usually for about $20,000 a film. A nominal fee, but the alternative was surrendering to rampant piracy and getting nothing. By the 1990s, China was allowing a few U.S. films into China every year on a revenue-sharing basis, including hits like Warner Bros's The Fugitive, Paramount's Forrest Gump and Disney's The Lion King, according to the book China's Encounter with Global Hollywood (University Press of Kentucky, 2016) by Wendy Su. But the dollars for Hollywood were still small, with studios only getting about 13 percent of ticket sales, according to Chris Fenton, a production executive who has done business with China for more than two decades.

Since a deal was struck in 2012, China now allows 34 foreign films into the country annually and the studios get 25 percent of the box office with the rest going to Chinese firms, including government-owned distributors China Film Group and Huaxia Film Distribution Co.. But movie industry insiders, speaking on condition of anonymity, say 34 is more a floor than ceiling, especially since studios can co-produce with a Chinese company and thus avoid having their movie classified as "foreign." That was the case with The Great Wall which featured Matt Damon and a cast of Chinese and western supporting actors, in 2016, and the upcoming Top Gun: Maverick.

"The fact that major American blockbusters have been casting Chinese film stars, or even filming scenes in China, as a way to capture their moviegoers' attention is extremely telling," says Jeff Bock, a senior analyst with Hollywood data firm Exhibitor Relations Co. "While studios don't receive as large a cut from the box office in China as they do domestically or in other territories, the growth potential is staggering and worth the risk."

Jamie Chen, a Shanghai-based senior analyst at investment firm Third Bridge Research, agrees, pointing out that while about 1,000 films are produced annually by China's domestic film industry only about 400 of them are deemed worthy of theatrical release. Even prior to COVID-19, "the vacancy rate in Chinese cinemas was huge," Chen says. That leaves a large void for U.S. studios to fill—if they are willing to play ball.

Those considering not playing have long had the example of Richard Gere to consider. On the red carpet outside the 1993 Oscars, Gere, then near his A-list star peak, protested China's "horrendous" occupation of Tibet. Gere has said his continuing stand on Tibet seriously damaged his career as the Chinese market grew in size and importance. In 2017, Gere, who declined to speak to Newsweek, told an industry trade publication, "I recently had an episode where someone said they could not finance a film with me because it would upset the Chinese." (Similarly, Brad Pitt's role in 1997's Seven Years in Tibet reportedly landed him on China's do-not-cast list for a while, though in 2013 World War Z was allowed to open in Hong Kong where it earned a modest $5.5 million).

Since then Hollywood filmmakers have gotten used to Chinese interference over things big and little. Producer Jerry Molen, who has produced several Steven Spielberg movies including Schindler's List, says often the meddling is about trivia. "The Chinese will ask for everything expecting to get something," he says. "Sometimes, it's an actor or scenes filmed in China. It doesn't mean you have to show Shanghai, Beijing and The Great Wall in all their glory, but you can never show them in a bad light." In 2018, Molen was executive producer on The Meg, a co-production of Warner Bros. and China Media Capital about an enormous prehistoric shark. The hero scientists in the movie are Chinese. The film was a box office success, earning $530 million worldwide, $153 million coming from China.

For Disney's 2013 Iron Man 3, state-owned China Film Group wanted a hospital scene to be filmed in one of its then-new sound stages in Beijing. Producer Chris Fenton was at time president of Beijing-based DMG Entertainment Motion Picture Group which released the film in China. He's now CEO of Media Capital Technologies and the author of Feeding the Dragon: Inside the Trillion Dollar Dilemma Facing Hollywood, the NBA & American Business, which Post Hill Press will release on July 28. Fenton says, "The floors were made of faulty, cracked bricks that slowly disintegrated into dust as the crew and equipment moved over them, The bricks coughed up more and more dust to the point where we all needed to wear masks in order to breathe." Ultimately, most of the hopelessly foggy hospital footage was unusable.

A Chinese requirement for co-productions with foreigners is that there be only one version shown worldwide, effectively allowing Chinese censors to decide what international audiences can see. Producer Matthew Malek, who has helped get multiple U.S. movies into Chinese theaters says, "Even when the Chinese tell you they just want control over what's seen in China, the contracts they send over have a clause that the China version becomes the master version. They don't admit that, but I've seen it enough times. There's no way around it, unless you're a giant studio that's created a movie knowing what the Chinese want from the beginning."

Sometimes the requirement can be finessed. On Iron Man 3 in 2013, Disney appeased Beijing by adding a few Chinese actors and products to the film—only for a version released in China. The same year, however, Paramount's zombie apocalypse thriller World War Z starring Brad Pitt was released. In Max Brooks's 2006 novel, scientists and doctors believe a pandemic of undead cannibalism had its start in China. There is no mention of that in the film. At the time of release, Paramount denied reports that a scene discussing China as possible zombie ground zero had been shot for a planned non-China version of the film, but cut when Chinese authorities insisted only one version be released worldwide.

Of the major studios, insiders say, Disney is the most successful at doing business with China, as the studio's ability to manage the authorities on Iron Man 3 shows. The company has successfully partnered with the government on its theme parks in Shanghai and Hong Kong, even replacing trademark attractions like Space Mountain with spectacular only-in-China rides at the insistence of authorities. Last year the studio's Avengers: End Game became the biggest grossing film in history, hauling in $2.8 billion worldwide, with $614 million, or about 22 percent, coming from China.

Similarly, Disney has high hopes for its upcoming live-action version of Mulan, based on the Chinese folk tale of a young woman who poses as a man to take her ailing father's place in the army. When a teaser trailer for the film went online last year, 52 million people in China watched it in the first 24 hours. But last summer in the midst of a growing crackdown on dissent in Hong Kong, actor Liu Yifei, who plays the title character, tweeted her support of the Hong Kong police. The backlash was swift and loud and spawned an ongoing campaign to boycott the movie when it opens. After Liu's tweets, Twitter suspended about 1,000 accounts boosting the hashtag #SupportMulan, saying they were Chinese state-backed bots designed to undermine "the legitimacy and political positions of the protest movement."

While studios like Disney have worked hard to get along with China, some filmmakers have spoken out. Speaking on a panel at the 2014 Beijing International Film Festival director Oliver Stone said he had tried and failed three times to complete co-productions with Chinese film companies due to meddling from authorities. One project was an adaptation of the memoir Red Azalea (first published by Pantheon Books in 1994) by Anchee Min, a lesbian love story set during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s. Same-sex relationships are forbidden by Chinese censors. 20th Century Fox cut all references to Freddie Mercury's homosexuality from Chinese prints of its 2019 hit Bohemian Rhapsody. Even more sensitive is any discussion of the Cultural Revolution and any criticism, implicit or otherwise, of Chairman Mao or the Communist party's actions during those agonizing years.

Last year, China blocked Quentin Tarantino's Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood over its portrayal of martial arts legend Bruce Lee. In the film, Lee, played by Mike Moh, is depicted as a preening blowhard who is fought to a draw by stuntman Cliff Booth, played by Brad Pitt. Lee's family didn't like it and neither did Beijing, which insisted it be cut from the film. Tarantino, the rare director who is able to insist on final cut, refused.

Wakeup Call?

If the push and pull between Hollywood and China has mostly been played out in offices and editing rooms, it has now begun to move to a much noisier arena. On May 21, Senator Ted Cruz introduced a bill dubbed SCRIPT ("The Stopping Censorship, Restoring Integrity, Protecting Talkies Act") that would cut off the help studios receive from the Department of Defense if they censor films to placate the Chinese.

"Hollywood companies have learned that China censors American films, so they often change their films in advance of submitting them to the Chinese market," Cruz tells Newsweek. "Chinese censors control not just what Chinese audiences see, but also what American audiences see." Cruz, one of three U.S lawmakers recently barred by Chinese officials, says his bill is a "wakeup call" to Hollywood and would also prevent the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security from helping studios that submit to Chinese censors. Cruz says the point is forcing producers "to choose between the assistance they need from the American government and the money they want from the Chinese film market."

Hollywood is not taking Cruz's bill very seriously. Producer Chris Fenton thinks it should. "Whether this particular bill gets momentum should not be the focus...Surveys have shown voters are wary of China, and it's an election year," he says.

Meanwhile Wisconsin Representative Mike Gallagher, a Republican, is lobbying U.S. studios to disclose when their films are presented—at every stage, from screenwriting through completion—to China's censors. What Gallagher has in mind is a notice in the credits like the "no animals were harmed in the making of this film" disclaimer many films carry.

A particularly egregious example of Hollywood appeasement of China, Gallagher tells Newsweek, is the 2012 remake of Red Dawn, produced by the small studio Film District along with MGM and Sony. When principal photography was over, the film was about a bunch of small-town American teens fighting off an invasion by China. In post-production, though, MGM and Sony digitally altered it so the invasion came from North Korea. Gallagher says he doesn't see any pro-Chinese Communist Party ideology in that kind of move by Hollywood, just a desire to make money. He says, "Filmmakers aren't waking up each morning thinking about the nature of the CCP, but it's fair to say they haven't woken to the threat it poses, either."

"Hollywood has difficult decisions to make between the bottom line and the values it stands for," says Gallagher. "Hollywood certainly has no reservations about preaching to Americans, and there's no shortage of movies portraying America as evil, bad and racist. But it certainly seems it's on the wrong side when it comes to China, which is engaged in ideological warfare."

This is the same ideological battle that the Soviet Union fought and lost when it tried to keep Western movies, music, books and ideas out during the Cold War. The Chinese learned an important lesson from that failure and decided not to ban Western culture. Instead, they have worked hard—and for the most part successfully—to co-opt it.

About the writer

Paul Bond has been a journalist for three decades. Prior to joining Newsweek he was with The Hollywood Reporter. He ... Read more